Our collective confusion about the American experience begins at the beginning. Most Americans who think about such questions imagine that they understand the Declaration of Independence, though many of them may be puzzled that it did not (and does not) produce the results one might expect from the commitments which they believe it makes. After much misleading, they take the task of interpreting it to be a belaboring of the obvious, even though they know very little about its text, its content, or the moment in history that produced it. For by the spokesmen for one tradition in American politics they have been carefully taught to apprehend the document in a certain selective way: that is, by the tradition usually acknowledged by press and electronic media, pulpit and textbook maker; the tradition which is perhaps too confident of itself, even though it has brought forward nothing in the way of proof for its favorite assumptions. So much is indeed self-evident truth.

Our collective confusion about the American experience begins at the beginning. Most Americans who think about such questions imagine that they understand the Declaration of Independence, though many of them may be puzzled that it did not (and does not) produce the results one might expect from the commitments which they believe it makes. After much misleading, they take the task of interpreting it to be a belaboring of the obvious, even though they know very little about its text, its content, or the moment in history that produced it. For by the spokesmen for one tradition in American politics they have been carefully taught to apprehend the document in a certain selective way: that is, by the tradition usually acknowledged by press and electronic media, pulpit and textbook maker; the tradition which is perhaps too confident of itself, even though it has brought forward nothing in the way of proof for its favorite assumptions. So much is indeed self-evident truth.

But it is likewise true that for the first one hundred years of our national existence the Declaration of Independence was usually understood in another way, according to a theory that reads its commitment to government based on “the consent of the governed” and to the aboriginal sameness of all men in their right to a certain order of political experience as a statement about citizens in their corporate character, as they enter the social state. In this tradition “all men” is taken as a statement about human nature that is made specific by subsequent language concerning the Creator. Men are formed to live under the authority of a particular sort of government. Or so the Signers maintained. The Marquis de Chastellux observed that they meant by “all men” primarily “all citizens or property holders”—substantial persons who owned land and probably slaves. Or all nations of men. The Marquis was attempting with this formulation to explain why almost no one among the colonial leaders of American society argued that the Declaration of Independence required of their country an internal social and economic revolution. In his opinion, by the word “people” they meant nothing so universal as the “half philosophers” among his countrymen sometimes intended when they spoke of humanity in general. He was quite correct in observing that the purpose of the American Revolution was to preserve (or restore) a known felicity, not to create a new one: not to transform and elevate mankind “in general,” even though we might, after the fact of independence, congratulate ourselves for having done so. Certainly the forms taken by the declarations of rights adopted in most of the original thirteen states would seem to support his argument. For a majority of them speak of the status of men “once they enter into a state of society,” or (like South Carolina) refuse to speak of rights at all. The Virginia Declaration of Rights was drawn specifically so as to prevent misunderstanding about any disposition to free the slaves. Other documents are careful about the suffrage. But I believe there is a better way of deciding what is meant by “all men are created equal” than by falling back upon circumstantial paraphrase of an astute French observer. For I think the Declaration can be read according to the canons of formalist literary criticism, as a structure, as a literary artifact or system within which each component modifies and reinforces the implications of every other paragraph, phrase or word operating within the whole.

From the very beginning of the Declaration of Independence, the voice that addresses us is plural: issuing from one group of people toward mankind at large. It presupposes a “people,” most of whom think of political life as occurring through their participation in some collectivity: or by way of several such identities operating simultaneously. And it presupposes other nations of men (and men within nations) as audience. The last sentence of the Declaration which encapsulates its form also speaks of a “we” who pledge “our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor.” And throughout the text there is evidence that everything which is maintained subsists in the plural. Taken that way, the second sentence of the Declaration concerns the minimum grounds for the acceptance of a government by the people who live under it: that it not threaten the lives or properties or hopes for a future entertained by its citizen members; that it at least do better than the Great Turk. Taken this way, the human nature (and natural law) affirmed by the Declaration is the minimum expectation that may be assumed as the ground for the legitimacy of the state. God made men for civil life, but not for an absolute submission to a state that promises them no protection in return and denies them the hope of improving their condition. All men are created equal (i.e., are alike) in this respect. For such a total state to claim a right to obedience goes against the God-given qualities of human nature.

Part of the way of testing these assumptions about interpreting the Declaration of Independence comes from asking questions about what happens to the coherence of the text if its prologue is said to deal with the natural rights of pre-social individuals. Only thus is sentence two an epitome of the entire document. Understanding equality in the opposite fashion, however, creates fewer problems. Writes Daniel Boorstin, recently our Librarian of Congress, “We have repeated that ‘all men are created equal,’ without daring to discover what it meant and without realizing that probably to none of the men who spoke it did it mean what we would like it to mean.” Just before the adoption of the Declaration, the Virginia Convention on May 15, 1776 urged that the Congress “declare the united colonies free and independent states” on the grounds of “the eternal [i.e., natural] law of self-preservation.” Hence a phrase concerning all men (i.e., human communities) and their expectations of any government not merely tyrannical. The list of offenses under English law charged against King George III and Parliament and the body of the Declaration work outward from the given elements of law to the necessity for a prologue concerning the collective reaction to tyranny in North America. The spirit of all this material derives from the Glorious Revolution of 1688 when James II had forfeited his crown after setting himself above the law that made him king—with the English constitution being sovereign, not the will of the prince.

Above and beyond English law is the tradition alive in all Christian civilization that legitimate authority, “government long established,” should be obeyed, even though it is sometimes mistaken in its operations: that there should be no revolution for “light and transient causes.” George III in his 1775 “Proclamation for Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition” had put his North American subjects beyond the protection of law, and then made war on them. He had fostered servile insurrections, he had armed savages and had otherwise offended against “the common blood.” These charges cannot logically coexist with an egalitarian and universalist prologue of the kind usually assumed in the now conventional reading. If origin and history and belief make no difference, why is it wrong to hire German troops or to offer freedom to the slaves or the means of self-defense to the Indians? Only by maintaining (as Lincoln does) that most of the Declaration is unimportant can the advocates of the popular version of its meaning sustain their position. Lifting three or four words out of context, they sail along merrily. On the other hand, if the text means what Stephen Douglas and Jefferson Davis, Henry Clay and Franklin Pierce thought it meant—that Americans are not inferior to Englishmen as a citizenry—then all of its parts work together to one effect, especially Jefferson’s ironic comments about a “Christian King” who has “plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.” As a matter of fact, we know that the bill of particulars maintained at law is what the Signers of the Declaration thought to be important about it. Even though it is true that when representative government is established, and operates regularly over a period of time, it has as one of its side effects a degree of equalization, giving incidentally more liberty to more persons: true despite the fact that there is no design at work to effect such a purpose. About these republican developments no one complained—and no one but Charles Pinckney generalized, observing how rare were our “official” inequalities.

With so much said concerning the formalist technique for reading the Declaration of Independence as a forensic whole, a political bill of divorcement, I am now ready to make a few observations on the status of the document as it relates to the United States Constitution. Legal separation on grounds drawn from the English constitution was a necessary preliminary to independence, to the receipt of French and Dutch assistance and to the Confederation of those erstwhile colonies who speak with the authority of their instructions from the various legislatures as a “we” joined in revolution and assembled in the Continental Congress. For that reason the Declaration is printed in the United States Code Annotated just before the Articles of Confederation. Independence and confederation were prologue to Union. And the Articles of Confederation as a gloss upon the second sentence of the Declaration warns us not to make that sentence a promise of either equality of condition or equality of opportunity for all of the inhabitants of the new country. Mr. Lincoln at Gettysburg notwithstanding, Willmoore Kendall was correct when he maintained that “the Declaration of Independence does not commit us to equality as a national goal.” The document creates no authority at law. It does not mandate any legislation or policy. It alters the status of no man or woman—except as it preserves to them a portion of their heritage under the now broken British constitution. It is not a prologue to the United States Constitution. For that instrument says almost nothing about equality of any kind.

The Declaration of Independence neither obligates nor binds Court or Congress in any way—as American statesmen specify repeatedly in the period running from 1790 through 1820. Moreover, the notion that the Declaration was designed to have one meaning in its own time and another one today, sometimes the doctrine of President Lincoln, goes against everything that we know about human nature in that it imagines Christian men obliging their children and grandchildren to conduct vast and potentially dangerous social and political experiments that they are unwilling to see attempted in their own time and place. That a decision to proceed in this way was made by an entire generation no sensible person can believe. I call this the “ticking bomb theory” of the Declaration. It is impressive only to those anachronists who have a special interest in discovering hidden meanings in materials that have heretofore seemed to be obvious in their burden; the expression of a sentiment that becomes a command. Since these theorists of unfolding meanings can find little to encourage them in the speech, writings, or conduct of the Framers, we cannot take them very seriously. As for those who, in the tradition of abolitionist jurisprudence like that of Senator Charles Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens, would sift the Constitution back and forth through the Declaration of Independence until it is swallowed up by their view of that text, I can only respond with the language of Justice James Iredell, who in the 1798 case of Calder v. Bull observed that “ideas of natural justice are regulated by no fixed standard” and are no basis for setting aside the acts or decisions of legislative powers. The legislative process, he argued, was the place for revisions of the national identity, especially by way of amendment.

Modern scholars, jurists and legal historians—such as are indeed chiefly interested in what the Constitution ought to say—are often surprised by its general silence on the laws of nature and the rights of man, its procedural, nomocratic character. Like Carey McWilliams in his afterword to the recent Ratifying the Constitution, they are often disturbed at not finding such an emphasis in our fundamental law or in the context which originally gave it force and authority. But if they are generally in search of the truth of things, they can do no other than agree with McWilliams that “the Constitution made no explicit appeal to natural right” and that this omission was functional since Governor Edmund Randolph maintained (on May 29, 1787), just before proposing what we now know as the Virginia Plan for replacing the Articles of Confederation, that the subject before the Great Convention was not “human rights” but how to get over too much democracy—”requisitions for men and money” and stable government.

As reported and summarized by Charles Warren, Randolph in Philadelphia says he is against “such a display of theory . . . since we are not working on the natural rights of men not gathered into society but upon those rights modified by society and interwoven with what we call the rights of the States.” According to this teaching, “natural rights may be dangerous [to the entire social and political fabric of American life] . . . since the Constitution presumes the existence of and seeks to protect [i.e., secure] conventional rights.” In the same spirit spoke Colonel Joseph R. Varnum of Massachusetts, who in that state’s ratification convention, insisted that Congress, under the Constitution, had no right to alter the internal relations of a state; and Theophilus Parsons, famous attorney and judge from the same state, who “demonstrated the impracticability of forming a bill in a national constitution for securing . . . individual right.” So also spoke Alexander Hamilton in the New York ratifying convention at Poughkeepsie: “Were the laws of the Union to now model the internal police of any state [or to] penetrate the recesses of domestic life, and control, in all respects, the private conduct of individuals—there might be more force in the objection [made against that Constitution].” And George Champlin of Rhode Island at South Kingston: “This Constitution has no influence on the laws of the States.” But whether safe or potentially harmful, powerless or imperial in nature, according to Justice Iredell, the Constitution cannot be assumed to enact natural rights since these were meant to be defined under the police power of the states and localities: in the phrase of Edmund Pendleton, “our dearest rights in the hands of our state legislatures.”

Of course, from time to time someone in Congress made reference to the Declaration before the War Between States. Lincoln’s allusions to that text are well known. And after the War, radical Republican spokesmen in the Congress appealed to the Declaration’s statement about aboriginal equality whenever they were advocating Reconstruction amendments or legislation supposed to have special effect on the South. Other Republicans (and the Democratic minority) did not agree to act on such a basis. And the Chase, Waite, and Fuller Courts (to say nothing of those that followed) denied that metaphysical, a priori equality was part of the Constitution. The modern Court has of course made reference to the Declaration from time to time. Consider Gulf C&S F Railroad v. Ellis, 165 U.S. 150 (1897); Butchers Union Co. v. Crescent City Live-Stock Co., 3 U.S. 746 (1884); Northern Pipeland Co. v. Marathon Pipe Line Co., 458 U.S. 50, 60 (1982); United States v. Will, 449 U.S. 200 (1980); Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579,641 (1952); Nevada v. Hall, 440 U.S. 410, 415 (1979); South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 359 (1966); Parklane Hosiery Co. v. Shore, 439 U.S. 322, 340 (1979); and Faretta v. California, 422 U.S. 806, 829 (1975). But these adversions to the Declaration in rulings by the Supreme Court are mostly of recent vintage. And none of the cases where they are found depend primarily on the Declaration for their authority. They merely drag it in for color.

Moreover, with legislative and judicial references to the Declaration there is always the problem of which version of that document, which reading, has been invoked—as when the Black Republicans on June 16, 1906, got a guarantee that the original state constitution for Oklahoma should contain nothing “repugnant to the Constitution of the United States and the principles of the Declaration of Independence” written into the Enabling Act allowing that territory to take such steps toward statehood. And then, one year later, allowed the Sooner State to enter the Union under basic laws providing for the establishment of a segregated system of schools. It is not the simplistic version of the Declaration of Independence that played a part in these events. Though to this day—as witness Mortimer Adler’s We Hold These Truths—the old Neoabolitionist convention for twisting the Constitution into a gloss and expansion upon the Declaration continues to hold its place in the political thought of the American Left and to function as an alchemical instrument for transforming the U.S. Constitution without legislation or amendment.

What the Declaration meant (and means) it achieved by way of its form. That significance is visible in what men did about its adoption. And in what they did not do.[1]

Reprinted with the gracious permission of The Intercollegiate Review, Fall 1992.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Notes:

1. What I have taught previously concerning the Declaration of Independence appears in chapters of my A Better Guide Than Reason: Studies in the American Revolution (Peru, Illinois; Sherwood Sugden, 1979). They are in sequence, “The Heresy of Equality: A Reply to Harry Jaffa” (29–57); “All to Do Over: The Revolutionary Precedent and the Secession of 1861” (153–167); and “Lincoln, The Declaration and Secular Puritanism: A Rhetoric for Continuing Revolution” (185–203). Related material appears in Remembering Who We Are: Observations of a Southern Conservative (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1985), xvii, 41–42; in The Reactionary Imperative: Essays Literary and Political (Peru, Illinois: Sherwood Sugden, 1990), 123–124, 141–142; and also in Against the Barbarians and Other Reflections on Familiar Themes (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1992), 60–63, 220 and 235. The locus of Professor Willmoore Kendall’s thought on the Declaration is in the book finished for him by his friend George Carey, Basic Symbols of the American Political Tradition (Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, 1970), 75–95, 152–156. Also useful in discussing this question is his essay “Equality: Commitment or Ideal?,” reissued in The Intercollegiate Review 24 (Spring 1989): 25–33.

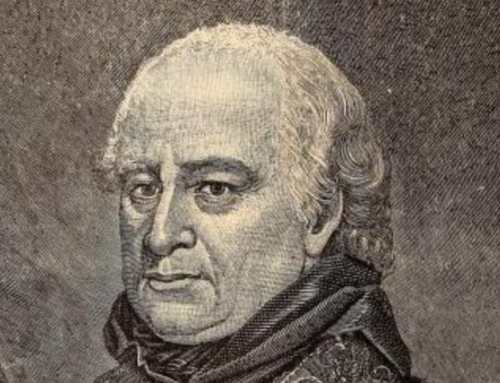

The featured image is “The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776” (1845) by Edward Hicks (1780-1849), courtesy of WikiArt.

Leave A Comment