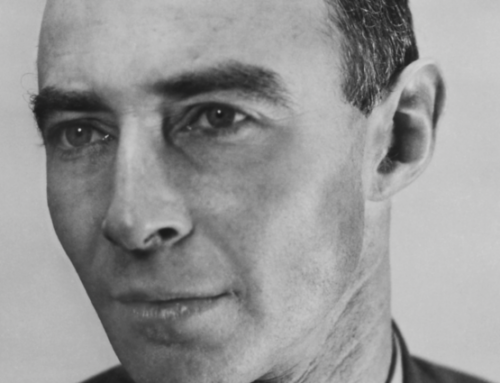

French filmmaker Eric Rohmer (1920-2010) created an impressive oeuvre of fine films. I first encountered him through the DVD box-set from The Criterion Collection containing six of his films known as the “Six Moral Tales.” The set also contains a 262-page paperback book of the six stories that Rohmer originally wrote, upon which he later based the movies. No doubt the literary quality of the films’ stories can be attributed to this fact of their origin. The highly articulate characters that populate his films, and fill them to overflowing with interesting conversations for our eavesdropping, exhibit the artist’s unique literary sensibility for an acute observation of human character.

French filmmaker Eric Rohmer (1920-2010) created an impressive oeuvre of fine films. I first encountered him through the DVD box-set from The Criterion Collection containing six of his films known as the “Six Moral Tales.” The set also contains a 262-page paperback book of the six stories that Rohmer originally wrote, upon which he later based the movies. No doubt the literary quality of the films’ stories can be attributed to this fact of their origin. The highly articulate characters that populate his films, and fill them to overflowing with interesting conversations for our eavesdropping, exhibit the artist’s unique literary sensibility for an acute observation of human character.

Recently I came across a film of Rohmer’s that I had not seen before. One of the few available in Canada though Apple’s iTunes, the tantalizing description of 4 Adventures of Reinette and Mirabelle billed it as “a criminally overlooked gem” from Rohmer. Intrigued, I immediately purchased it, and as I watched the opening credits roll, electronic pop music and retro graphics conjured a nostalgic mood. I was therefore unsurprised when the credits announced the film was made in 1986.

The movie is divided into four episodes, deceptively leading one to believe that the story could be considered as merely episodic. In fact, there is one overarching story, with a literary quality, tying everything together. It unifies the themes of the four episodes. True, the episodes themselves could be viewed separately, on their own, as “Four Moral Tales.” Yet, when joined together, the resultant whole magically becomes more than the mere sum of its parts. Moreover, the final result artfully conceals the careful craft and design of a master filmmaker, one who likes to leave us with the misleading impression that his camera randomly follows people’s relatively aimless actions.

The film’s four episodes are titled: “The Blue Hour,” “The Waiter,” “The Beggar, the Kleptomaniac, and the Hustler,” and “Selling the Painting.” In the first episode, the city girl Mirabelle meets the country girl Reinette by chance when she is out cycling through the countryside. The two women hit it off. Reinette is a painter with untutored natural talent. The result of this first episode, simply in terms of plot, is that Reinette, in quest of an education, will move to the city to become Mirabelle’s roommate.

The film’s four episodes are titled: “The Blue Hour,” “The Waiter,” “The Beggar, the Kleptomaniac, and the Hustler,” and “Selling the Painting.” In the first episode, the city girl Mirabelle meets the country girl Reinette by chance when she is out cycling through the countryside. The two women hit it off. Reinette is a painter with untutored natural talent. The result of this first episode, simply in terms of plot, is that Reinette, in quest of an education, will move to the city to become Mirabelle’s roommate.

But the most significant aspect of the first episode is that nature-girl Reinette desires to wake Mirabelle up so that she will experience the special time of night in the country known as “The Blue Hour.”

“All farmers know about that time of night,” says Reinette. It is a time of perfect silence, when the night birds stop their singing and the day birds have yet to begin theirs. According to Reinette, it teaches us “the finest lesson in humility.” Explaining what she means, she says: “We need nature, not the other way around.”

I won’t spoil the movie for you, because you should watch it in order to enjoy its rare qualities. My own tastes are such that this is my favorite type of movie. Perhaps that is because I am a natural-born philosopher who spends a lot of time with books and in conversation with many interesting people. However, I will give you some hints about the unifying thread, in order to give clues about what to be on the lookout for, in order to experience maximum enjoyment of the film.

In “The Waiter,” Reinette’s naïve, country-girl honesty clashes with a big-city French waiter of the most archetypically arrogant kind. His cranky cynicism is paired in equal measure with his outrageous injustice. This vivid episode affords Reinette, in dramatic fashion, to firmly show us, in response to this scandalous encounter, her insistent moral rectitude.

Yet the longer she stays in the city, the more Reinette proceeds to learn about the pressures of human hardship. In the third episode, “The Beggar, the Kleptomaniac, and the Hustler,” a series of fascinating, morally-charged encounters permit us to follow Reinette’s progressive education. She becomes more and more subject to the harrowing influence of the city environment in which she lives. Her development is paired with Mirabelle’s, who is placed by Rohmer in a supermarket scenario that requires her morally to define herself. This also invites us to compare her to Reinette.

In the fourth and final episode, “Selling the Painting,” the trajectory of Reinette’s character arc reaches a surprising and satisfying conclusion, in a partnership with Mirabelle. The theme of silence, and the idea of nature’s silent presence as a moral standard for us all, which was originally announced thematically in the first episode, is taken up again. In a dazzlingly brilliant, dramatic scenario, Reinette’s education is complete as she collaborates with Mirabelle in a daring scheme that also permits us to meditate on the essence of artistic expression among human beings.

In the fourth and final episode, “Selling the Painting,” the trajectory of Reinette’s character arc reaches a surprising and satisfying conclusion, in a partnership with Mirabelle. The theme of silence, and the idea of nature’s silent presence as a moral standard for us all, which was originally announced thematically in the first episode, is taken up again. In a dazzlingly brilliant, dramatic scenario, Reinette’s education is complete as she collaborates with Mirabelle in a daring scheme that also permits us to meditate on the essence of artistic expression among human beings.

Not many films can match the power of 4 Adventures of Reinette and Mirabelle’s unexpectedly delightful and simultaneously disturbing conclusion. This is especially so because the episode’s morally decisive incidents resonate with all the overtones artfully established in the preceding episodes. Perhaps the most exquisite aspect of the film’s conclusion is the incomparable irony with which Rohmer treats the new development in the lives of Reinette and Mirabelle. Silence now reigns supreme here in the city, but is it the same sort of silence that the “Blue Hour” offers?

In one of the film’s funniest sequences, the city girl Mirabelle pleads for silence from a loquacious Reinette. The irony of this particular reversal, established in direct contrast to the film’s first episode, is an irony that only deepens with the film’s conclusion. In the end, the two women have learned, not so much how to speak, as how not to speak of unspoken moral truths.

The ancient Chinese philosopher, Lao Tzu, began his Tao Te Ching, the classic work of the Taoist school of thought, with this arresting first sentence:

道可道,非常道

Tao k’o tao, fei ch’ang tao.

“The Tao that can be put in words is not the ever-abiding Tao” (trans. Keith Seddon)

In The Abolition of Man, C.S. Lewis observed:

The Tao, which others may call Natural Law or Traditional Morality or the First Principles of Practical Reason or the First Platitudes, is not one among a series of possible systems of value. It is the sole source of all value judgments. If it is rejected, all value is rejected. If any value is retained, it is retained. The effort to refute it and raise a new system of value in its place is self-contradictory. There has never been, and never will be, a radically new judgment of value in the history of the world. What purport to be new systems or (as they now call them) ‘ideologies,’ all consist of fragments from the Tao itself, arbitrarily wrenched from their context in the whole and then swollen to madness in their isolation, yet still owing to the Tao and to it alone such validity as they posses.

Thomas Aquinas, in his “Treatise on Law” (Summa Theologiae, I-II, 90–114), in question 94 on the natural law, article 4, offers what we could take as an explanation of the puzzling affirmation that Lao Tzu announced at the outset of his own classic meditations. Aquinas wrote: “in speculative matters truth is the same in all men, both as to principles and as to conclusions, although the truth is not known to all as regards the conclusions, but only as regards the principles which are called common notions. But in matters of action, truth or practical rectitude is not the same for all as to matters of detail, but only as to the general principles; and where there is the same rectitude in matters of detail, it is not equally known to all.”

Not only that, but from the observation of human behavior, it seems an additional distinction can be made: namely, that an education in moral rectitude is something that can either be gained or lost. In Eric Rohmer’s cinema, we are the beneficiaries of a gimlet-eyed filmmaker, one who is consistently devoted to chronicling the errant moral history of unforgettable individuals.

Not only that, but from the observation of human behavior, it seems an additional distinction can be made: namely, that an education in moral rectitude is something that can either be gained or lost. In Eric Rohmer’s cinema, we are the beneficiaries of a gimlet-eyed filmmaker, one who is consistently devoted to chronicling the errant moral history of unforgettable individuals.

In film after film, he places people in the most quotidian, yet most fascinating, of moral dilemmas. Perhaps the uncompromising nature of Rohmer’s artistic pursuit, which above all feels most like what Socrates could have accomplished if he had instead become a filmmaker, is the reason why his oeuvre as a whole should be called “criminally overlooked.” After all, people are hesitant to praise a moral gadfly, especially one most charming and urbane.

Books on the topic of this essay may be found in The Imaginative Conservative Bookstore.

Leave A Comment