Ronald Reagan did not read his way to conservatism, as some people do. He experienced his way. The concerns and travails of middle Americans taught him that unaccountable government could be a grave obstacle to the pursuit of happiness, and the experience of dealing with Communists and bureaucrats strengthened his lifelong distrust of overbearing elites.

In the autumn of 1948, as Harry Truman campaigned to remain president, the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union produced a pro-Truman radio advertisement that aired on stations across the country. The fifteen-minute program had two principal speakers: a liberal Minnesota politician named Hubert Humphrey, on his way to being elected that year to the U.S. Senate, and an equally liberal motion picture actor named Ronald Reagan.

Speaking from Hollywood, Reagan lambasted the bête noire of liberals everywhere in 1948: the “do nothing,” Republican-controlled Eightieth Congress, which he held responsible for the nation’s current economic misery. It was “Republican inflation,” Reagan charged, that was eroding workers’ paychecks while the profits of giant corporations were soaring. In fact, said Reagan, the recent surge in consumer prices had been caused by these “bigger and bigger profits.” “Labor has been handcuffed by the [recently enacted] vicious Taft-Hartley law,” Reagan continued. Social Security benefits had been “snatched away from almost a million workers” by a recent bill in the Republican Congress. Meanwhile the Republicans had enacted tax cuts that benefited “the higher income brackets alone.” “In the false name of economy,” he concluded, “millions of children have been deprived of milk once provided through the federal school lunch program.”[1]

This is not the Ronald Reagan whom most Americans remember today. Far more familiar to us is the movie star who took to the airwaves sixteen years later, in 1964, in support of another presidential candidate: Barry Goldwater. Reagan entitled his nationally televised address “A Time for Choosing,” but the choice he recommended was very different from what he had favored in 1948. The enemy he identified now was not big business or “Republican inflation”; it was Communism abroad and an out-of-control leviathan state at home. In 1948 Reagan had applauded Harry Truman’s attempts to expand the welfare state, including Social Security. In 1964 Reagan peppered his remarks with examples of governmental waste and failure, called for Social Security to have “voluntary features,” and asserted that “outside of its legitimate functions, government does nothing as well or as economically as the private sector of the economy.” “If we lose freedom here, there’s no place to escape to,” Reagan warned his television viewers. Freedom “has never been so fragile, so close to slipping from our grasp as it is at this moment.”[2]

What happened to Ronald Reagan between the 1940s and the 1960s? In assessing the careers of statesmen and other leaders, we often focus on the continuities in their lives: the permanent qualities of mind and spirit that propel them to greatness. But in the case of Reagan, we clearly must do more. We must plumb the depths of the great discontinuity in his life, the discontinuity that in the end made all the difference: his conversion from a man of the left to a man of the right.

* * *

Ronald Reagan grew up in Illinois as a child of Democrats. His father, Jack, an Irish Catholic and a shoe salesman, had been a devoted Democrat for years. In 1932, near the nadir of the Great Depression, young Ronald, aged twenty-one, cast his vote for Franklin Roosevelt for president. He did so again in 1936, 1940, and 1944. Throughout these years he was known as “a very, very avid” Roosevelt Democrat.[3] “I am a sucker for hero worship,” Reagan wrote years later.[4] During the high tide of the New Deal and well beyond, the hero he worshipped was FDR.

When Reagan moved to California in 1937 to begin his acting career, he entered a world much more politically “progressive” than the small-town Midwest he left behind. In Hollywood, New York City, and other centers of cultural fashion, the late 1930s were the heyday of the Popular Front, a loose alliance of liberals, socialists, and Communists who cooperated in public campaigns and protests against the growing menace of fascism in Europe. To many on the American left in this period, the members of the vocal Communist Party seemed less like the minions of a cruel despotism in Moscow than homegrown “liberals in a hurry”—acceptable allies in the resistance to Nazism. So they appeared to more than a few politically engaged people in Hollywood, where Communists and their fellow travelers were a not insignificant presence.

According to sources cited by one of Reagan’s biographers, in 1938 the handsome young actor from Illinois was briefly attracted to Hollywood’s Red flame. It seems that in a moment of rash idealism, Reagan attempted to become a member of the Communist Party, only to be turned down as unreliable by the local party boss. The party evidently preferred to keep the callow enthusiast on the outside, as a potentially useful “friend.”[5]

Whatever the accuracy of this story (which Reagan later denied), nearly everyone who knew him in the late 1930s and early 1940s agreed that his consuming offscreen passion was politics and that his political stance was “very liberal.”[6] An omnivorous reader with a photographic memory, Reagan effortlessly stored up in his head an amazing array of statistics and knowledge with which he cheerfully bombarded anyone who would listen. A pro-Communist filmmaker who worked closely with him during World War II later remarked that Reagan “had more knowledge of political history than any other actor I’d ever met.”[7] Genial but zealous, the FDR loyalist liked nothing better than to debate politics by the hour with conservative Republican friends, each trying in vain to convert the other to his position. Curiously, two of these early right-wing sparring partners—the actor George Murphy and the California businessman Justin Dart—would help to launch Reagan’s career in politics, as a conservative, twenty years later.

But in the early 1940s this denouement was nowhere in sight. After the United States entered World War II, Reagan eventually found himself in uniform. For most of the war, he served in California, where he rose to captain in the First Motion Picture Unit of the U.S. Army Air Forces. Here he performed administrative tasks and helped to prepare military training films. During this period, the no-enemies-on-the-left spirit of Popular Front liberalism—temporarily eclipsed by the notorious Hitler-Stalin pact of 1939—had returned in force, and Reagan again felt its gravitational pull. With the United States and the Soviet Union allied in war against Nazi Germany, it was not surprising that in 1943 he joined the Hollywood Democratic Committee, a Popular Front–style mélange of liberals and hard leftists devoted to encouraging President Roosevelt’s conciliatory policy toward Stalinist Russia. The committee’s executive director was a member of the Communist Party.

In 1944 Reagan went to a Roosevelt reelection rally in Hollywood. During the war, he also showed interest in attending what a far-left Army colleague later described as “left-wing functions.”[8] Whether he actually did so in any serious way is unclear. Most likely his few political gestures in this period betokened little more than a desire to stay in touch with like-minded liberals while waiting for the war to end—at which time he could again release his crusading and proselytizing impulses.

Years later, reflecting upon his wartime experience in uniform, Reagan wrote that it had led to “the first crack in my staunch liberalism.” While in the Army, he had been obliged to deal with the bureaucratic inanities and “empire building” of the Civil Service.[9] Nevertheless, when Reagan returned to civilian life (and a full-time Hollywood acting career) in 1945, he was, by his own admission, a “near-hopeless hemophilic liberal” and “a New Dealer to the core.”[10]

I thought government could solve all our problems just as it had ended the Depression and won the war. I didn’t trust big business. I thought government, not private companies, should own our big public utilities; if there wasn’t enough housing to shelter the American people, I thought government should build it; if we needed better medical care, the answer was socialized medicine.[11]

Determined to do his part for “the regeneration of the world,”[12] Reagan excitedly plunged into a frenzy of left-wing activism, including contacts with at least five organizations later accused of being Communist fronts.[13] On December 10, 1945, he read aloud an anti-nuclear poem at a formal dinner where other speakers denounced nationalism and capitalism and demanded international control of nuclear weapons. The popular movie star joined and quickly became a “large wheel” in the aggressively liberal American Veterans Committee (AVC), whose California ranks included more than a few Communists and fellow travelers. He joined the Hollywood Independent Citizens Committee of the Arts, Sciences and Professions (HICCASP), the Popular Front–style successor to the Hollywood Democratic Committee. He signed up with the World Federalists, whose policy goals included a world government. He even put his name on a petition by an outfit called the Committee for a Democratic Far Eastern Policy, demanding that the United States abandon China’s anti-Communist leader Chiang Kai-shek (who was then fighting a civil war against the Chinese Communists). The petition was soon printed in the Communist Party’s West Coast newspaper.

Above all, in the first months after the war Reagan went on a speaking spree around Hollywood, decrying what he saw as the rise of “neofascism” in the United States. It is little wonder that during these heady months he was “a favorite of the Hollywood Communists.” “I was their boy,” he ruefully admitted a few years later.[14]

Otto von Bismarck once reputedly remarked: “Fools say they learn by experience. I prefer to profit by others’ experience.” In early 1946 Ronald Reagan was neither a fool nor a Communist sympathizer. But like many Roosevelt Democrats at the time, he was, by his later account, an innocent who was “not sharp about Communism” and the true nature of the Soviet despotism.[15] He was a non-Communist, not yet an anti-Communist. He was about to learn the political facts of life the hard way.

Reagan’s slow political awakening took place amid a tectonic shift beneath the landscape of the American left. The war against Nazi Germany had not quite ended in 1945 when Joseph Stalin laid down a new line for obedient Communists worldwide: with Hitlerism all but destroyed, a new enemy had arisen—American imperialism—and Communists must prepare to struggle against it. The halcyon era of the prewar and wartime Popular Front, in which “progressives” could happily unite against fascism, was over. In its place Stalin had inaugurated a new struggle—the Cold War—in which the focus of evil for Communists everywhere would be Washington, D.C. No longer could the American comrades sing hosannas to Franklin Roosevelt and to Soviet-American friendship. Under direct orders from the Kremlin, they must now confront the “reactionary,” “warmongering” administration of Harry Truman. Up to now the American Communist Party had been able to portray itself as a patriotic part of the grand coalition against Hitler. Now, in the quickening Cold War, the Party was forced to show what it really was: a witting tool and agent of a totalitarian, foreign power.

Meanwhile Reagan had begun orating around Hollywood under the auspices of the American Veterans Committee about the alleged threat of domestic “neofascism.” His “hand-picked” audiences loved it. But then, one evening in the spring of 1946, upon the advice of his minister, the liberal celebrity altered the conclusion of his speech. After first denouncing fascism to the usual “riotous applause,” he added a new closing line: “I’ve talked about the continuing threat of fascism in the postwar world, but there’s another ‘ism,’ Communism, and if I ever find evidence that Communism represents a threat to all that we believe in and stand for, I’ll speak just as harshly against Communism as I have against fascism.” The audience reaction, in Reagan’s word, was “ghastly”: not a single person applauded as he left the stage. He was stunned.[16] His turn to the right, it may be said, commenced that very night.

A few weeks later, on July 2, his disillusionment deepened when he attended his first meeting as a member of HICCASP’s executive council, to which he had recently been appointed. HICCASP was already beset by accusations that it was Communist-controlled. To allay these concerns, James Roosevelt (a son of FDR) proposed at the meeting that the council issue a statement repudiating Communism. Instantly howls of outrage burst forth from John Howard Lawson (the “dean” of Hollywood’s Communists) and other radicals in the room. When Reagan, the newcomer, rose in support of Roosevelt’s proposal, he was greeted by shouts of “Fascist,” “Red-baiter,” and “capitalist scum,” among other vituperative epithets of the Communist lexicon. The verbal brawl ended in the appointment of a committee of the two factions to draft an acceptable policy statement. It also ended in Reagan’s joining the anti-radicals for a strategy session later that evening.

A few nights later, Reagan and the non-Communists on the drafting committee met with their leftist colleagues. Reagan’s side offered a draft resolution (partly written by Reagan himself) ending with these words: “We [the executive council of HICCASP] reaffirm our belief in free enterprise and the democratic system and repudiate Communism as desirable for the United States.” Once again pandemonium erupted. Shaking his finger under Reagan’s nose, Lawson shouted that HICCASP would never adopt such a statement. “Let’s let the whole membership decide by secret ballot,” Reagan replied; this matter “shouldn’t be left to the board of directors.” Lawson retorted that the membership “isn’t politically sophisticated enough to make this decision.” Reagan never forgot the chilling, authoritarian condescension of those words.

The drafting committee eventually thrashed out a compromise resolution that ducked the question of Communism and watered down the reference to free enterprise. The HICCASP’s executive council adopted this version with amendments a few days later. When Reagan’s ally Olivia de Havilland then submitted the more anti-Communist resolution to the council’s executive committee, it received exactly one vote: her own. A few weeks later HICCASP’s executive council declared that it had no “affiliation” with any political party, including the Communists. For Reagan and many other Hollywood liberals, this anemic statement was a case of “too little, too late.” In the aftermath of the stormy meetings in early July, he and many other prominent liberals resigned. To Reagan, HICCASP’s refusal to unequivocally affirm democracy and repudiate Communism was “all the proof we needed” that the organization had indeed become a Communist front, “hiding behind a few well-intentioned Hollywood celebrities to give it credibility.” Only weeks before, he had been inclined to dismiss talk of Communist infiltration and manipulation as “Red-baiting” and “Republican propaganda.” No more. He had discerned, as he later put it, “the seamy side of liberalism. Too many patches on the progressive coat were of a color I didn’t personally care for.”[17]

Reagan’s eye-opening entanglement with Communist front groups was only a prologue to the political education he was about to receive in the workplace. In 1946 the motion picture industry in Hollywood was in turmoil, riven by costly strikes and threats of strikes almost constantly. Forty-three different labor unions represented the film industry’s workforce, and two of these—the two largest—were at war: the International Alliance of Theatrical and Stage Employees (IATSE), dominated by militant anti-Communist Roy Brewer, and the Conference of Studio Unions (CSU), headed by hard-core leftist Herbert Sorrell, with strong support from the Communists. The immediate source of friction between these giants seemed, at first glance, ludicrously petty: which one of them should have jurisdiction over a few dozen stage set erectors? But this was merely a flashpoint in a struggle for supremacy that was approaching a showdown. In late September, under pressure from Brewer’s union and the studio bosses (who favored IATSE), Sorrell’s CSU went out on strike. Mass picketing and confrontations ensued. The IATSE men and many other unions worked anyway. The “battle of Hollywood” was on.

The crisis brought to center stage the Screen Actors Guild (SAG), of which Reagan was now a director, and on whose strike emergency committee he served. The strike had placed SAG in the driver’s seat. The actors knew that if they honored the CSU’s job action, they could bring the entire industry to a halt: if no actors showed up for work, no films could be produced. The IATSE would be outflanked, and the studios would have to capitulate to the CSU. But was Sorrell’s job action defensible? Or did he, a suspected Communist, have less savory motives? If the CSU’s goal was simply better wages and working conditions for its members, SAG would be under pressure to respect the picket lines. But if Sorrell and his henchmen were staging a jurisdictional strike—designed to encroach upon and ultimately destroy a rival union—the screen actors would have no moral obligation to refrain from work.

Although initially sympathetic to the CSU, Reagan and his associates quickly concluded that the CSU strike was in fact merely jurisdictional: in Reagan’s later words, a “phony.” Reagan reported this conclusion on October 2 to the SAG membership, which voted overwhelmingly to cross the picket lines and ignore the strike. At the same time, Reagan and his colleagues attempted strenuously for months to be the peacemakers and bring the IATSE and the CSU to terms. The Screen Actors Guild got nowhere.

Eventually Reagan concluded that the hardboiled Sorrell and his allies did not want to settle the strike but instead to profit from the “continued disorder and disruption” engulfing Hollywood. Sorrell, for his part, issued an “international appeal” to boycott films by Reagan and other actors who crossed the picket lines. Inside the Screen Actors Guild, a faction accused Reagan of favoring the movie producers and demanded that SAG support the CSU. But at a mass outdoor meeting of 1,800 SAG members on December 19, 1946, Reagan delivered a lengthy report on all that he and his fellow SAG directors had done in good faith to resolve the dispute. His speech was a tour de force. The membership endorsed SAG’s board of directors’ conduct by a margin of 10-to-1. Three months later Reagan was elected the guild’s president.

Meanwhile, on the streets and studio grounds of Hollywood, the battle raged on. From the start it was a brutal affair. Rioting was frequent; mobs of picketers were arrested by the hundreds. Nonstrikers were beaten with clubs and chains and were hospitalized by the score. Homes of nonstrikers were firebombed and their cars overturned. Buses carrying nonstrikers to the film studios were assaulted with bottles and rocks. One morning the bus that was to take Reagan and fellow actors to work that day through the picket line was bombed and burned.

Early in the strike, after word circulated that Reagan was about to report to SAG that the CSU strike was merely “jurisdictional,” he received an anonymous phone call: “I was told that if I made the report a squad was ready to take care of me and fix my face [with acid] so that I would never be in pictures again.” The next day Reagan was issued a loaded revolver, which he carried in a shoulder holster for self-protection for several months. For a time police stood guard at his home.

Without the support of the actors, the CSU’s job action was doomed. More than seven months after the walkout began, it ended in failure. Like Roy Brewer of IATSE (who became a lifelong friend), Reagan came to believe that the long, acrimonious confrontation had been staged and manipulated by the Communists, using Sorrell and the CSU as their accomplices and tools. Citing later governmental investigations and other sources, he charged that a “hard core” of Communists under the “direct orders of the Kremlin” intended first to paralyze the fractured motion picture industry and then, in the ensuing chaos, to bring into being a single giant union encompassing all film industry employees—a union they planned to dominate. The Communists further intended, said Reagan, to place this union under the control of the West Coast longshoremen’s union, run by a veteran Communist, Harry Bridges. The “minor jurisdictional disputes” that touched off the strike, Reagan concluded, had been a mere pretext for advancing an audacious “scheme”: the complete capture of “the American motion picture business” in order to finance the work of the Communist Party and in due course “subvert the screen” with pro-Communist propaganda.[18]

Then and later, Reagan’s critics challenged his interpretation of events as simplistic, but he never wavered from it and took pains to offer supporting evidence.[19] The searing experience distanced him from Popular Front liberalism once and for all. For the rest of his life, he disdained “‘liberals’ [who] just couldn’t accept the notion that Moscow had bad intentions or wanted to take over Hollywood and many other American industries through subversion, or that Stalin was a murderous gangster. To them, fighting totalitarianism was ‘witch hunting’ and ‘red baiting.’ ”[20]

A few years after the strike, actor and former Communist Sterling Hayden told a congressional committee that during the 1946 strike (when Hayden was still a Communist) he had been ordered to try to win support for the CSU among his fellow members of the Screen Actors Guild. He made little headway, he testified, because he ran into an anti-Communist “one-man battalion” named Ronald Reagan.[21] Hayden was not off the mark. Thanks in considerable measure to Reagan and his allies in the Screen Actors Guild, the CSU’s bid for dominance had been foiled. For years to come, Reagan told spellbound audiences the story of how he and SAG had successfully thwarted the Communists’ “big push” in 1946 to “invade our industry.”[22] There was more truth than bravado in his sobering claim.

Reagan emerged from the “battle of Hollywood” a determined anti-Communist and a wiser man. He was not, however—not yet—a conservative. He remained an avowed Democrat and liberal, albeit a chastened one. In 1947 he joined Americans for Democratic Action (ADA), a new organization of pro–New Deal, anti-Communist liberals who supported President Harry Truman’s policies and fought the farther-left brand of progressivism espoused by former vice president Henry Wallace. The ADA portrayed itself as the champion of a liberalism of the “vital center,” eschewing Communists and their dupes on the far left and reactionary, anti–New Dealers on the right. Its luminaries included Eleanor Roosevelt, Hubert Humphrey, and Arthur Schlesinger Jr. Reagan—a popular figure among liberals of this stripe in Hollywood—helped to organize the ADA in Southern California and became a member of the national board of directors. Although not especially active (he did have an acting career to pursue and protect), he considered the ADA “the only voice for true liberals” and remained a member for at least three years.[23]

In 1948 Reagan enthusiastically supported Harry Truman’s bid to stay in the White House. When the embattled president’s campaign brought him to Los Angeles in September, Reagan was invited to dine with him and stood near him on the platform at the rally. Less than two weeks later, Reagan helped to launch, and became chairman of, the Labor League of Hollywood Voters, whose purpose (in Reagan’s words) was “to fight against Communism” and help reelect Truman. The league denounced the far-left (and Communist-dominated) Progressive Party and its presidential candidate, Henry Wallace.[24] In 1950 Reagan endorsed the liberal Democratic congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas in her losing race for the U.S. Senate against Richard Nixon. And in 1952, for the second time, he was approached by Democrats about running for Congress.[25]

Like millions of other Democrats that year, Reagan voted for the Republican, Dwight Eisenhower, for president—a sign, perhaps, of the actor’s drift toward the right.[26] But that very same year he also publicly opposed two local Republican candidates for Congress in California on the grounds that they had unfairly criticized the motion picture industry’s attempts to rid itself of Communist influence.[27] Reagan had become a resolute enemy of the Reds, but—like many in his profession—he resented attempts by publicity-seeking politicians to barge in and “clean up” Hollywood.

Indeed, by the standards of the late 1940s and early 1950s, Reagan’s anti-Communism was comparatively moderate. In 1947 he publicly opposed the outlawing of the Communist Party; it would be, he suggested, “a dangerous precedent.”[28] He was forgiving of those, like himself, who had briefly been caught up in the Red smog. He told a Hollywood columnist: “You can’t blame a man for aligning himself with an institution he thinks is humanitarian; but you can blame him if he deliberately remains with it after he knows it’s fallen into the hands of the Reds.”[29] Calling himself a liberal, he declared: “Our highest aim should be the cultivation of the individual, for therein lies the dignity of man. Tyranny is tyranny, and whether it comes from right, left, or center, it’s evil.”[30]

Later that year, when the House Committee on Un-American Activities held hearings on Communism in Hollywood, Reagan testified as a “friendly” witness, but he did not grovel before a group he considered “a pretty venal bunch.”[31] Citing Thomas Jefferson to the effect that “if all the American people know all of the facts they will never make a mistake,” he argued that the antidote to Communist infiltration of American life, including Hollywood, was “to make democracy work.” “I still think democracy can do it.”[32]

For the next four and a half years, as president of the Screen Actors Guild, Reagan endeavored, by his lights, to do just that, even as he sought to deprive the Communists of any remaining influence over the film industry. It was not an easy task, and Reagan was accused, then and later, of collaborating in a sordid industry blacklist of leftists (a charge he vehemently denied). What stands out, in retrospect, was his effort at SAG to provide procedures for repentant radicals and the falsely accused to clear their names. One of these would be a woman who became his second wife.

In 1948 Reagan’s marriage to the actress Jane Wyman ended in a painful divorce: a rupture in part caused, she asserted, by his total immersion in Hollywood politics—an obsession that had bored her and driven her to distraction.[33] Reagan was devastated. A couple of years later, a Hollywood starlet named Nancy Davis noticed that another Nancy Davis was being mentioned publicly as a supporter of Communist causes and that the non-Communist Miss Davis was receiving Communist literature in the mail because of it. Fearful that her career in Hollywood might be jeopardized by the confusion, Miss Davis the actress asked the Screen Actors Guild to confirm her lack of Communist taint—which Reagan, after checking the files, duly did. But the worried young lady insisted on personal reassurance from SAG’s president—a request that soon led to a dinner date and instant romance. They married in 1952.[34]

It is sometimes said that Reagan’s second wife was instrumental in turning her husband to the right. There is no evidence to support this speculation. But Nancy’s unbending stepfather, Dr. Loyal Davis, a renowned brain surgeon, was an outspoken conservative, and it is possible that his opinions on socialized medicine (for example) may have eventually rubbed off on his son-in-law. Thanks in part to Dr. Davis, new and more conservative acquaintances began to enter Reagan’s circle of friends. Among them was the doctor’s neighbor in Phoenix, Senator Barry Goldwater.[35]

All this was happening while Reagan was one of the best-paid and most prominent personalities in Hollywood. As president of the Screen Actors Guild from 1947 to 1952, and as a member of its board of directors for some time thereafter, he was now more than just another celebrity. He was a high-profile spokesman for the industry and one of its principal defenders against its critics. As an officer (and eventually president) of the newly founded Motion Picture Industrial Council (a trade association of sorts), he was in the novel position of being an advocate for a big business: his business. His opinions on its problems—from Communists to meddlesome politicians, from small-town film censors to intrusive local gossip columnists, from foreign governments’ discrimination against American films to the U.S. government’s discrimination against actors in the federal tax code—were sought out and reported in the press.

Despite the lingering unpleasantness of the Communist controversy, Reagan remained much admired around town. His charm, prestige, and inexhaustible fund of humor made him a popular speaker and master of ceremonies at social and civic events.[36] By 1961 he had appeared at more than one thousand fundraising benefits for “good causes.”[37] In 1952 he was invited to deliver the commencement address at William Woods College in Missouri. His speech, entitled “America the Beautiful,” was an inspiring paean to America’s exceptional place as a land of liberty among the nations—a theme that cast a bright gleam into his maturing political soul.[38]

Around 1950 Reagan began to hit what he called the “mashed potato circuit” in defense of his embattled industry. He did not yet know it, but the logic of his advocacy was to drive him far from Trumanesque New Dealism and ever closer to a militantly libertarian brand of conservatism.

* * *

Reagan’s case for his profession was developed in what he later called “my basic Hollywood speech,” which he delivered at the Kiwanis International Convention in June 1951, and elsewhere on innumerable occasions.[39] The actor portrayed his industry and community as a victim of “more misconceptions and misinformation . . . than any other spot on earth.” Contrary to the stereotype, he contended, Hollywood was not full of feckless immoralists and Communists but of normal, reputable, largely churchgoing people who were defending America in one of the crucial battle zones of “the ideological struggle that is going on on the [movie] screens of the world.” He contended that the American film industry was “operating in the best manner of free enterprise,” without ever having sought government aid or subsidies “of any kind.”

Reagan assured his listeners that the Communists in Hollywood had been “licked.” Nevertheless, he warned, the industry and our “democratic institutions” generally were under attack from certain “enemies of democracy and our way of life.” One enemy was the “political censorship” of movies, an evil afflicting “over two hundred cities in the United States.” It threatened to create “an entire generation of Americans” conditioned to accept without protest the idea that someone could tell them what they could see and hear and perhaps even read.

The other “insidious” attack, Reagan warned, came from the federal government’s tax policies toward Hollywood. No industry, he thundered, “has been picked for such discriminatory taxes as have the individuals” in the movie business. He prophesied that “if they can get away with it there, it is aimed at your pocketbook and you are next.” And he warned that “you can’t lose a freedom anyplace without losing freedom everyplace.”[40]

For the rest of the 1950s, Reagan hammered away at these concerns. As the film industry slid into a prolonged, postwar recession, exacerbated by the rise of television, he came more and more to see federal tax and regulatory policies as a significant source of the industry’s troubles. In 1948 the Supreme Court held that the big Hollywood studios were in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. The studios were compelled to divest themselves of their theater chains—a heavy blow, in Reagan’s opinion, to the structural stability and prosperity of the business. President Truman did not help matters by proposing to close a tax loophole that allowed filmmakers and actors to trim their taxes considerably. Nor did Congress calm the waters when a certain senator introduced a bill to license movie actors and permit only moral ones to appear on screen.[41]

As Reagan analyzed the industry’s mounting difficulties, he began to see something he had never noticed before: a U.S. government in “adversarial relationship with its own business community.”[42] After reciting a litany of the industry’s complaints, he wryly told one audience that “we in Hollywood have a suspicion that when you ask the government for help, you are likely to wind up with a partner.”[43] In 1958, as a film industry spokesman, he testified before Congress in favor of reducing federal income taxes, especially the “confiscatory” rates at the top of the tax structure. The existing tax system, he claimed, with its strongly progressive and “excessive” rates for the highest earners, was stifling the entire motion picture business, since the most successful actors and writers had no incentive to make more than one or two films a year. Why should they, when nearly all of their annual income over $200,000 would be taxed away from them? And since the people at the pinnacle of the film business were working at less than full capacity, everyone dependent on them for work (like camera crews and stagehands) was suffering also. Reagan argued that if tax rates were lowered, the resulting stimulus to “business and investment” plus the “normal growth of the economy” would actually cause the government’s “share of the national income” to increase instead of decline. It was a remarkable foreshadowing of what would become known twenty years later as “supply side economics.”[44]

For Reagan, of course, the existing tax system had more than theoretical interest. In 1944 he had signed a lucrative acting contract guaranteeing him a total income of a million dollars over the next seven years. Financially he was at the peak of his profession. The trouble, he remarked some years later, was that this “handsome money lost a lot of its beauty and substance going through the 91 per cent bracket of the income tax.” He felt that he was being penalized for his success, and it angered him.[45] His son Michael never forgot his father’s frown one day around 1954 as he told his boy, “I don’t get to keep very much of the money I earn.”[46] In a lighter vein, Reagan advised a congressional tax committee: “If I could keep 50 cents on the dollar I earned, I would be too busy in Hollywood to be here today.”[47] But the wound went deep, and his rhetoric intensified accordingly. By the late 1950s, he was telling audiences, including Congress itself, that America’s progressive income tax system had “many features that can only be defended by endorsing the principles of the Socialism we are sworn to oppose.”[48]

Gradually the ideological furniture was rearranging itself in Reagan’s mind. The onetime member of Americans for Democratic Action had discovered that government could be a dangerous foe as well as a friend. It was a decisive and transformative insight.

Nevertheless, in 1954 Reagan was not yet the full-throated libertarian conservative he would shortly become. He was still a creature of the rarefied world of Hollywood and, on paper at least, a Democrat. In 1953 he chaired the committee to reelect the liberal mayor of Los Angeles, a Democrat, against a Republican opponent. But his ongoing crusade to defend Hollywood against “discriminatory taxation” and “needless government harassment”[49] had planted seeds of doubt about welfare state liberalism—seeds that were soon to sprout in spectacular fashion.

In 1954 Reagan’s professional life veered in an unexpected direction. He became the host and production supervisor of a weekly, televised dramatic series, General Electric Theater, sponsored by the General Electric Corporation.[50] For the now middle-aged actor, whose career had been languishing lately, the opportunity came as a godsend: the company agreed to pay him $125,000 per year (later raised to $150,000)—a figure equivalent to at least $1 million today. For his corporate sponsor, the new show and its celebrity host held out the promise of exposing millions of consumers to GE’s goods and services, marketed under the slogan “Progress Is Our Most Important Product.”

GE’s hopes were more than fulfilled. On Sunday evening, September 26, 1954, General Electric Theater under Reagan’s supervision debuted on national television to immediate acclaim.[51] As both host and an occasional performer in the weekly, half-hour, original dramas, Reagan brought onstage as guest stars a glittering array of Hollywood talent. By 1959 more than twenty-five million Americans a week were tuning in.[52] In its eight years on the air, General Electric Theater was the most-watched program in its time slot until its final season, and one of the most popular shows on television.

As part of his arrangement with his sponsor, Reagan agreed to become its “general good-will ambassador,” touring its plants and participating in its social functions. Almost alone among great American corporations in 1954, GE was highly decentralized, with more than 130 plants in nearly forty states.[53] GE’s chairman, Ralph Cordiner, conceived the idea of dispatching his television spokesman on visits to these facilities as a form of morale-building for the employees.[54] Even before the first episode of General Electric Theater went on the air, Reagan began traveling to the far-flung outposts of GE’s empire.

It was grueling work, lasting sometimes for weeks before Reagan got to go home again. Because of his fear of flying, he traveled by train or automobile, with a GE handler always by his side. The hours were long, frequently from dawn to after midnight. In one five-day tour of New England in late 1954, he “addressed five Good Neighbor fund meetings; made four TV and four radio appearances; attended 12 receptions, luncheons, and dinners; addressed five miscellaneous groups; toured five departments at the River Works, West Lynn, Bridgeport, and Plainville; and got writer’s cramp from signing well over 1000 autographs.”[55]

And this was only the beginning. By early 1956 Reagan was delivering as many as thirteen speeches a day to company employees and local community organizations. On one memorable day in Lynchburg, Virginia, in 1957, he gave eighteen separate talks (or was it twenty-five)?[56] His GE traveling companion on that trip found him a “veritable bionic man, all stamina and drive.”[57]

Initially, most of Reagan’s engagements were simple meet-and-greet affairs on local plant premises, where he would make a few remarks and take questions from starstruck employees. But GE’s management quickly discovered his talents as a speechmaker. Before long his scheduled events included luncheon talks and dinner addresses to local Rotary Clubs, chambers of commerce, and similar groups. By 1957 his handlers were scheduling his formal appearances far in advance, and at ever more distinguished venues, as his reputation spread.

At the outset Reagan recycled the familiar elements of his “basic Hollywood speech,” such as his battles against the Communists and his biting critique of federal tax discrimination against the film industry. But then a funny thing began to happen. After hearing his denunciations of federal harassment and unfair tax rates, people in his audiences would come up to him and say: You’ve got troubles in your business? Well, so do we in our business! Whereupon his listeners would pour out examples of governmental arrogance, intrusiveness, and overregulation that were “encroaching on liberties” in their lives.[58]

This reaction from his audiences seems to have startled Reagan and caused him to rethink his residual New Deal attitude toward government. Here we come to a crucial observation: when Reagan became part of the GE entourage in 1954, he was still in his own mind a liberal—and a strong union man, to boot. Although incensed by his high taxes and by governmental meddling in Hollywood’s business, he was not yet an across-the-board free-marketeer. Two GE executives who worked intimately with him during his mid-1950s tours recall having “fierce debates” with him in which he lauded the New Deal and defended the Democratic Party “to the last.”[59] The conservative GE aide who traveled with him from 1955 to 1962 remembered “arguments running for days or weeks” during the mid-’50s. Reagan, he remarked, was “the least malleable man I ever met.”[60]

Nevertheless, chinks in what was left of his liberal armor were becoming visible. Sensitive to the feedback from his audiences, Reagan began to look into their stories and read more widely about current affairs. In doing this, he worked entirely on his own. He conducted his own research and composed his speeches without assistance. Nor did anyone at GE ever try to tell him what he should or should not say.

What did Reagan read in this critical period? Surprisingly, it is a question that cannot be answered comprehensively. Although Reagan was, by his own account, an “inveterate” reader, he later admitted that it would be “hard for me to pinpoint” any books that had influenced his “intellectual development.”[61] In 1965 a Reagan biographer visiting his home noticed on the bookshelves “dog-eared and annotated” copies of three books hugely popular among American conservatives in the 1950s: Whittaker Chambers’s anti-Communist classic Witness (long passages of which Reagan could recite from memory); Henry Hazlitt’s free-market primer Economics in One Lesson; and the nineteenth-century French author Frédéric Bastiat’s anti-statist tract, The Law.[62] It is not known precisely when Reagan discovered these works. It is known that in 1945 he read the Reader’s Digest condensed version of Friedrich Hayek’s anti-socialist bestseller The Road to Serfdom, but it obviously made little impression at the time.[63]

Far more crucial for Reagan’s intellectual reorientation was the growing number of hard-hitting conservative magazines and advocacy groups that were beginning to alter the political climate of the 1950s. In addition to avidly reading the monthly Reader’s Digest (as he had been doing for years), he at some point discovered the conservative weekly newspaper Human Events, which he later said “helped me stop being a liberal Democrat.”[64] He also—again, the date is uncertain—began to read the libertarian monthly The Freeman, published since 1954 by the Foundation for Economic Education, headed by Leonard Read, with whom Reagan became a correspondent.

Also influential, in all likelihood, was the highly conservative corporate culture of GE to which he was now exposed: above all, the unending torrent of pro-free-market newsletters, pamphlets, and instructional materials disseminated to GE employees by the company’s tireless vice president of employee and community relations, Lemuel R. Boulware. A devotee of free market economics and a consummate propagandist, Boulware had a crusading temperament like Reagan’s and a desire to make others believe. The two men became friends during Reagan’s GE years, and Reagan undoubtedly read much of Boulware’s literature.[65] Boulware may also have purchased for Reagan a charter subscription to National Review, the conservative magazine founded by William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955.[66] Reagan became an enthusiastic and lifelong reader: “I’d be lost without National Review,” he wrote Buckley in 1962.[67]

It is no disparagement of Reagan’s intellect to suggest that it was from the Reader’s Digest, National Review, and similar magazines, plus Boulware’s barrage of free-market publications, that Reagan derived most of the source material for his increasingly popular, and increasingly ideological, speeches in the mid-to-late 1950s. The actor-turning-evangelist was not a disciplined scholar, nor did he have time to be. Like some other men of affairs of an intellectual bent, he was an autodidact, gathering up knowledge in sometimes indiscriminate ways. But he was bright, intellectually curious, and eager to make sense of the grievances against government that he was hearing from the “box office” (his audiences). He was also, no doubt, eager to please. Pithy, informative pamphlets and magazine articles were ideal reading matter on his frequent rail journeys around the country. Easy to stuff in his pocket and read on the run, they became an invaluable source of lively anecdotes, apt quotations, and startling statistics that Reagan, with his remarkable memory, could readily absorb and eventually put to good use.

Reagan later called his GE tours “almost a postgraduate course in political science for me.”[68] He was not thinking so much of what he read but of what he experienced during these long journeys: the faces, the voices, and the good sense of middle Americans. “Meeting the people was an unforgettable experience,” he told a friend in later years. “It confirmed a belief I’d always held that politicians as well as film producers underestimated and lacked understanding of John Doe American.”[69] He “realized I was living in a tinsel factory. And this exposure brought me back.”[70] It reinforced his growing aversion to arrogant elites who presumed to tell the rest of America how to live.

By his third year as GE’s roving “ambassador,” Reagan’s speeches to corporate and civic groups had supplanted his factory tours in importance. He now began to talk less and less about Hollywood’s problems and more and more about “the threat of government” to everyone.[71] An early sign of this shift was his commencement address at his alma mater, Eureka College, in June 1957. Five years earlier, in his commencement address at William Woods College, he had extolled “America the Beautiful” as a “promised land”—“the last best hope of man on earth.” In 1957 he spoke again in similar terms but with a crucial twist. America, he declared, was engaged in an “irreconcilable conflict” between “those who believe in the sanctity of individual freedom and those who believe in the supremacy of the state.” But the threat, he now asserted, was found not just abroad but here at home. “[A] great many of our freedoms have been lost,” he contended, and it was not “an outside enemy” that had taken them. “It’s just that there is something inherent in government which makes it, when it isn’t controlled, continue to grow.” “Remember,” he warned, “that every government service, every offer of government financed security, is paid for in the loss of personal freedom.” Whenever anyone urges you to “let the government do it, analyze very carefully to see whether the suggested service is worth the personal freedom which you must forego in return for such service.”[72]

With these words Ronald Reagan effectively crossed the political Rubicon. During the next half dozen years, he articulated his message with increasing vehemence and alarm. Speaking before the Executives’ Club of Chicago in the spring of 1958, he declared that “the revolution of our times is collectivism,” “the tendency of all of us to turn to the government for the answer to everything—centralizing of authority in one central body of government.” He castigated the nation’s tax code as the “machine” of this “revolution.” A year later, at a dinner in Schenectady, New York, he took issue with those who claimed that taxes could not be cut until government spending was cut first. “No government in history,” he rejoined, “has ever voluntarily reduced itself in size. Government does not tax to get the money it needs; government always finds a need for the money it gets.” Americans were losing their freedom, he told a GE interviewer afterward. The government’s tax burden on the economy was endangering “our private enterprise system.”[73]

A few months later, in a letter to Vice President Richard Nixon, Reagan reported his amazement at the reaction his set speech was getting from audiences around the nation. He was “convinced” that “a groundswell of economic conservatism” was “building up” and that it “could reverse the entire tide of present day ‘statism.’”[74] “Economic conservatism”: for the first time, perhaps, he used this term to describe his new identity. Ronald Reagan had become a man of the right.

By 1960, Reagan later wrote, he “had completed the process of self-conversion.”[75] It was a revealing phrase. No outside proselytizer, he seemed to suggest, had led him down the sawdust trail. No one else had coaxed or compelled him to switch direction. Instead, by a long and arduous process, he had changed himself.

But there had been a supporting cast, as it were, in the final act of his ideological transformation. By the time Reagan’s affiliation with General Electric ended, in 1962, he had visited every one of its 135 (or more) plants. In his eight years of work as GE’s “good-will ambassador,” he had delivered more than nine thousand extemporaneous speeches and had shaken the hands of at least 250,000 people. In the words of one of his General Electric associates, Reagan had been “saturated—marinated—in middle America.”[76] Out of this immersion in the dreams, frustrations, and grievances of ordinary Americans had come a libertarian, populistic conservative with a mission.

* * *

Irving Kristol once remarked that a neoconservative is a liberal who has been mugged by reality. This witticism has some relevance to our subject. In his later years, Reagan often minimized the extent of his political metamorphosis by claiming that he had not changed much at all. He had not left the Democratic Party, he came to believe; the Democratic Party had left him.[77]

This self-description was perhaps comforting to him, and politically astute, but it was not really true. To be sure, his idol Franklin Roosevelt had run in part on a conservative platform in 1932, but he had also promised a New Deal and had delivered one. After 1932, Roosevelt and most of the Democratic Party had moved leftward, and young Reagan had moved left along with them, until, under the influence of Popular Front liberalism, he had naively found himself for a time in the pink penumbra of the Communist Party.

What saved him from sliding further into its embrace? Amid the protracted U-turn of his later political development, one core conviction remained constant. At a memorial service in 1945 for a Japanese-American soldier who had lost his life fighting for the United States in World War II, Reagan (then a liberal) affirmed: “America stands unique in the world—a country not founded on race, but on a way and an ideal. Not in spite of, but because of our polyglot background, we have had all the strength in the world. That is the American way.”[78]

There it was: the embryonic affirmation of his unshakable faith in American exceptionalism, in American goodness, and in America’s destiny to be a beacon of liberty unto all nations. Holding this conviction, Reagan could never fall prey to Communist preachments that capitalist America was an inherently evil and reactionary force in the world and that an enlightened elite must lead a revolution to overthrow it. Reagan was always a democrat (with a small “d”). His belief in America’s exceptional character and democratic decency inoculated him against the temptations of the totalitarian left.

His all-American faith, however, did not instantly make him a conservative. As we have seen, his transition from left to right was a multiphasic process that unfolded over a number of years. Reagan did not read his way to conservatism, as some people do. He experienced his way. The ferocious war in Hollywood in 1946–47 (in which his life had been threatened) taught him many lessons; the government’s perceived harassment of Hollywood taught him more. The ravenous appetite of the progressive income tax taught him that not everything labeled “progressive” was good for one’s health. The concerns and travails of middle Americans taught him that Hollywood was not alone at risk and that an intrusive, unaccountable government could be a grave obstacle to the pursuit of happiness. The experience of dealing with Communists and bureaucrats strengthened his lifelong distrust of overbearing elites. The emerging popular literature of the postwar conservative movement then provided him a new frame of reference, as well as a source of wit and knowledge for increasingly powerful jeremiads against liberal statism.

How, then, did a “near-hemophilic liberal” movie actor in the mid-1940s become an impassioned conservative a dozen years later? In the final analysis, it came down to this: Ronald Reagan was mugged by reality.

Republished with gracious permission from Modern Age. (spring 2018). This essay was originally presented at a conference at Regent University.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Notes:

[1] Ronald Reagan and Hubert Humphrey radio speeches for Harry Truman’s presidential election campaign, n.d. (October 1948), under the auspices of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union. The nearly fifteen-minute program was aired on radio stations from coast to coast. A recording of it is in the Ronald Reagan Library, Simi Valley, California.

[2] Ronald Reagan, “A Time for Choosing,” October 27, 1964 (a nationally televised address for Barry Goldwater’s presidential campaign). A videotape of the speech is accessible online at YouTube. For a copy of the text, see Kurt Ritter and David Henry, Ronald Reagan: The Great Communicator (New York and Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982), 135–43.

[3] For Reagan’s early political beliefs and admiration for Franklin Roosevelt, see Anne Edwards, Early Reagan: The Rise to Power (New York: William Morrow, 1987). For Reagan’s “avid” support for Roosevelt, see the recollections of Jane Dart quoted in Doug McClelland, Hollywood on Ronald Reagan (Winchester, MA: Faber and Faber, 1983), 166.

[4] Jerry Griswold, “‘I’m a sucker for hero worship,’” New York Times Book Review, August 30, 1981, 11, 21.

[5] Edmund Morris, Dutch: A Memoir of Ronald Reagan (New York: Random House, 1999), 157–59, 719. From Morris’s sources, it appears that it took an emissary of the Party to talk Reagan out of wanting to join. It is not clear what arguments were persuasive.

[6] Bernard Vorhaus interview in Patrick McGilligan and Paul Buhle, Tender Comrades: A Backstory of the Hollywood Blacklist (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997), 674.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ronald Reagan with Richard G. Hubler, Where’s the Rest of Me? (New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1965), 123–25.

[10] Ibid., 139; Ronald Reagan, An American Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990), 105.

[11] Reagan, An American Life, 105.

[12] Reagan, Where’s the Rest of Me?, 140.

[13] Stephen Vaughn, Ronald Reagan in Hollywood: Movies and Politics (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 277–78, n. 45.

[14] John Cogley, Report on Blacklisting, I: Movies (New York: Fund for the Republic, 1956), 69.

[15] Reagan, Where’s the Rest of Me?, 141; Lou Cannon, Reagan (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1982), 74.

[16] Reagan, Where’s the Rest of Me?, 141–42; Reagan, An American Life, 106; Vaughn, Ronald Reagan in Hollywood, 130.

[17] Reagan, Where’s the Rest of Me?, 166–69; Reagan, An American Life, 105, 111–15; Vaughn, Ronald Reagan in Hollywood, 121–32. See also Reagan’s testimony in Jeffers v. Screen Actors Guild, reported in the Los Angeles Times, January 15, 1954, 17, and Reagan to Hugh Hefner, July 4, 1960, printed in Kiron K. Skinner, Annelise Anderson, and Martin Anderson, eds., Reagan: A Life in Letters (New York: Free Press, 2003), 147–49.

[18] The story of the strikes in Hollywood in 1946–47 is convoluted. The brief account given here has benefited from the following sources (listed in chronological order): contemporary accounts of the strife in the Los Angeles Times and New York Times; a series by James Bassett on Communism in Hollywood, published in the Washington Post, June 5, 6, and 8, 1951; Reagan testimony reported in the Los Angeles Times, January 14, 1954, A3; Cogley, Report on Blacklisting, I: Movies, 60–73; Los Angeles Times, June 10, 1957, 6; Reagan to Hefner, July 4, 1960; Reagan, Where’s the Rest of Me?, 142–65; Reagan, An American Life, 107–10; Morris, Dutch, 235–46; Lou Cannon, Governor Reagan: His Rise to Power (New York: Public Affairs, 2003), 86–90; Ronald Radosh, Red Star Over Hollywood: The Film Colony’s Long Romance with the Left (San Francisco: Encounter Books, 2005), 117–22.

[19] Reagan to Hefner, July 4, 1960; Reagan, Where’s the Rest of Me?, 157–64.

[20] Reagan, An American Life, 110.

[21] New York Times, April 11, 1951, 14; Reagan, Where’s the Rest of Me?, 173–74.

[22] See Reagan’s oft-given “basic Hollywood speech,” printed in Ronald Reagan, Speaking My Mind (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1989), 18–21. (The anti-Communist passage is on page 20.) See also Variety, October 24, 1956, 10, for an account of one of Reagan’s speeches on this subject.

[23] Vaughn, Ronald Reagan in Hollywood, 166–68. In June 1947 Reagan was a member of the ADA’s organizing committee for its Southern California section. See Melvyn Douglas to Philip Dunne, June 21, 1947, Melvyn Douglas Papers, Box 13, folder 4, Wisconsin Historical Society.

[24] Los Angeles Times, October 5, 1948, 5; Vaughn, Ronald Reagan in Hollywood, 158.

[25] The first time had been 1946. Cannon, Governor Reagan, 83.

[26] Cannon, Reagan, 90–91; Reagan, An American Life, 133. It was Reagan’s first vote ever for a Republican.

[27] New York Times, April 26, 1952, 18.

[28] Reagan interview with Hedda Hopper, printed in the Chicago Tribune, May 18, 1947, G7, and in the Los Angeles Times, May 18, 1947, B1.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Reagan interview with Lou Cannon, July 31, 1981, quoted in Cannon, Governor Reagan, 96.

[32] Cannon, Governor Reagan, 96–99. Reagan testified on October 23, 1947. For contemporary accounts, see New York Times, October 24, 1947, 1, 12, and Los Angeles Times, October 24, 1947, 1, 4.

[33] Los Angeles Times, June 29, 1948, A1. See also Reagan, Where’s the Rest of Me?, 175, 201–2.

[34] Reagan tells the story in Where’s the Rest of Me?, 233–40, and in An American Life, 121–23.

[35] Anne Edwards, Early Reagan, 482–83; Lee Edwards, The Essential Ronald Reagan (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2005), 37, 47.

[36] Many of these events were covered by the Los Angeles Times in the 1950s.

[37] Los Angeles Times, June 11, 1961, O15.

[38] Ronald Reagan, “America the Beautiful” (commencement address at William Woods College, June 2, 1952), printed in Davis W. Houck and Amos Kiewe, eds., Actor, Ideologue, Politician: The Public Speeches of Ronald Reagan (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1993), 4–10.

[39] Reagan, Speaking My Mind, 17–21; Congressional Record 91 (August 15, 1951): A5151, A5153–54.

[40] Reagan, Speaking My Mind, 17–21.

[41] Ibid., 17.

[42] Ibid., 18.

[43] Variety, October 24, 1956, 20. See also Reagan’s Executives’ Club of Chicago speech, May 2, 1958, printed in its Executives’ Club News 34 (May 8, 1958): 1–3, 6–10.

[44] Reagan testimony, January 27, 1958, printed in U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means, General Revenue Revision, 85th Congress, Second Session, 1980–83; Los Angeles Times, January 28, 1958, 8; Amos Kiewe and Davis W. Houck, A Shining City on a Hill: Ronald Reagan’s Economic Rhetoric (New York: Praeger, 1991), 12–18.

[45] Reagan, Where’s the Rest of Me?, 245; Reagan testimony, January 27, 1958, p. 1985.

[46] Michael Reagan with Jim Denney, The City on a Hill: Fulfilling Ronald Reagan’s Vision for America (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1997), 135–36.

[47] Reagan testimony, January 27, 1958, p. 1990.

[48] Ibid., p. 1988.

[49] Los Angeles Times, June 10, 1957, 6.

[50] Among the best accounts of Reagan’s GE years are the following primary and secondary sources (in chronological order): Reagan, Where’s the Rest of Me?, 251–73; Edward Langley, “How the Star Changed His Stripes,” Politics Today 7 (January/February 1980): 44; Edward Langley, “How Reagan Hit Road for GE and Met His Destiny,” Chicago Tribune, July 13, 1980, A1–A2, printed also (with some variations) in Knoxville Journal, July 14, 15, and 16, 1980; Francis X. Clines, “About Politics,” New York Times, July 24, 1980, A17; Earl B. Dunckel, “Ronald Reagan and the General Electric Theater, 1954–1955” (oral history interview, 1982), Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California; Anne Edwards, Early Reagan, 451–64; Reagan, An American Life, 126–38; Cannon, Governor Reagan, 107–114; Thomas W. Evans, The Education of Ronald Reagan: The General Electric Years and the Untold Story of His Conversion to Conservatism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006); Kim Phillips-Fein, Invisible Hands: The Making of the Conservative Movement from the New Deal to Reagan (New York: W. W. Norton, 2009), 87–115.

[51] GE Monogram, December 1954, 7. This was the General Electric Corporation’s publicity magazine for company managers and sales people.

[52] Ronald Reagan, “What Keeps the Theater on Top?” GE Monogram, September 1959, 19.

[53] In Where’s the Rest of Me?, 259, Reagan stated that GE had 135 plants. In An American Life, 127, he recalled that the company had 139 plants. His recollections also varied on the number of states where these were located (38, 39, or 40).

[54] Reagan interview with Lou Cannon, August 30, 1981, quoted in Cannon, Governor Reagan, 107–8.

[55] GE Monogram, October 1954, 16.

[56] Edward Langley of GE, who was traveling with Reagan that day, recalled the number as eighteen and twenty-five in separate reminiscences. Langley, “How the Star Changed His Stripes,” 44; Langley, “How Reagan Hit Road for GE . . . ,” A2.

[57] Langley, “How Reagan Hit Road for GE . . . ,” A2.

[58] Reagan, An American Life, 129.

[59] Langley, “How the Star Changed His Stripes,” 44; Langley article in Knoxville Journal, July 16, 1980; Dunckel oral history (1982), 22–23.

[60] George Dalen, quoted in Edward Langley’s article in Knoxville Journal, July 16, 1980.

[61] Michael S. Klausner, “Inside Ronald Reagan: A Reason Interview,” Reason, July 1975.

[62] Lee Edwards email to the author, December 17, 2010; Edwards, The Essential Ronald Reagan, 53–54; Paul Kengor, God and Ronald Reagan: A Political Life (New York: ReganBooks, 2004), 76–88.

[63] Lee Edwards email to the author, December 17, 2010.

[64] Lee Edwards, “Reagan’s Newspaper” (posted at the Human Events website, February 5, 2011).

[65] Evans, Education of Ronald Reagan, 74–75. The Lemuel R. Boulware Papers in the Annenberg Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Pennsylvania contain a file (folder 1435) of Boulware’s correspondence with Reagan. The men became lifelong friends.

[66] Langley, “How Reagan Hit Road for GE . . . ,” A1; Evans, Education of Ronald Reagan, 106.

[67] Reagan to William F. Buckley Jr., June 16, 1962, printed in Reagan: A Life in Letters, 281.

[68] Reagan, An American Life, 129.

[69] Reagan to Edward Langley, November 29, 1967, Ronald Reagan Gubernatorial Papers, Correspondence Unit: X-Files, Box 440, folder “Lang (1),” Ronald Reagan Library.

[70] Reagan, quoted in Cannon, Governor Reagan, 108.

[71] Reagan, An American Life, 129.

[72] Reagan commencement address, “Your America to Be Free,” July 7, 1957, at Eureka College, printed in Ritter and Henry, Ronald Reagan: The Great Communicator, 127–34. Accessible online here

[73] GE Schenectady News, January 23, 1959, 1, 5. See also ibid., January 30, 1959, 3.

[74] Reagan to Richard Nixon, June 27, 1959, in Reagan: A Life in Letters, 702.

[75] Reagan, An American Life, 134.

[76] Langley, “How the Star Changed His Stripes,” 44; Langley, “How Reagan Hit Road for GE . . . ,” A1; Clines, “About Politics,” A17; Cannon, Governor Reagan, 108.

[77] Dunckel oral history (1982), 15; Reagan, An American Life, 134.

[78] Quoted in Morris, Dutch, 228.

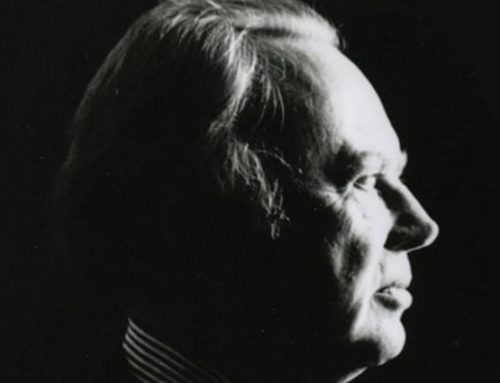

The featured image is a publicity photograph of Ronald Reagan sitting in General Electric Theater Director’s Chair, 1950s, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Leave A Comment