Henri de Lubac distilled Dostoevsky’s importance to our own times: “Yes, Dostoevsky was a prophet: because he not only revealed to man the depths that are in him but opened up fresh ones for him, giving him, as it were, a new dimension; because, in this way, he foreshadowed a new state of humanity.”

For the past three months or so, I’ve been discussing The Drama of Atheist Humanism by Henri de Lubac during the weekly sessions of the FORMED Book Club. Along with my co-hosts, Father Fessio and Vivian Dudro of Ignatius Press, we’ve been engaging with the insightful brilliance of the Jesuit theologian and philosopher as he grapples with the minds of four great atheist philosophers, Ludwig Feuerbach, Karl Marx, Friedrich Nietzsche and Auguste Comte. There is so much that I could say about de Lubac’s penetrative analysis of the ideas of these four men, each of whom has profoundly influenced the secular humanist culture in which we find ourselves, but I’d like to focus instead on de Lubac’s discussion of the great Russian novelist, Fyodor Dostoevsky.

For the past three months or so, I’ve been discussing The Drama of Atheist Humanism by Henri de Lubac during the weekly sessions of the FORMED Book Club. Along with my co-hosts, Father Fessio and Vivian Dudro of Ignatius Press, we’ve been engaging with the insightful brilliance of the Jesuit theologian and philosopher as he grapples with the minds of four great atheist philosophers, Ludwig Feuerbach, Karl Marx, Friedrich Nietzsche and Auguste Comte. There is so much that I could say about de Lubac’s penetrative analysis of the ideas of these four men, each of whom has profoundly influenced the secular humanist culture in which we find ourselves, but I’d like to focus instead on de Lubac’s discussion of the great Russian novelist, Fyodor Dostoevsky.

The third part of de Lubac’s book, entitled “Dostoevsky as Prophet”, examines how Dostoevsky’s novels serve as a response to the atheist humanism of his times and as a prophecy of the rise of Nietzscheanism and its consequences, as well as serving as the antidote to Nietzsche’s poison.

Beginning with a summary of the common misreadings of Dostoevsky’s work, de Lubac suggests that, “even when Dostoevsky stands revealed as a genius, he has not yet been understood”. Whereas his critics flounder in the shallows of perception, Dostoevsky dives and delves into the spiritual depths. He explores an “entirely different domain” to that of the atheists who remain trapped within either the confines and constraints of mere matter or the confines and constraints of the subjective egocentric self, both of which deny the existence of the spirit or the spiritual. Endeavouring to fathom “the domain of the spirit”, Dostoevsky looks into and through a “formidable unconscious” in order to catch a glimpse of a “mysterious beyond”. Nowhere is this made manifest more evidently, de Lubac writes, than in Notes from Underground:

In it, Dostoevsky declares some of the most exalted truths of any of his writings through the spokesman of a miserable and abject failure who explores the lower depths of his nature with cynicism. Dostoevsky’s underground represents both “the hidden world of the subconscious” … and the sacred cave in which the prophetic voice is raised.

Through such an approach, De Lubac insists, Dostoevsky “compels us to follow him in uncovering the spiritual depths of being”. In order to buttress his insistence on the primacy of the spiritual in Dostoevsky’s work, de Lubac then quotes Dostoevsky directly. “They call me a psychologist,” Dostoevsky wrote, “but it is not true: I am a realist in the highest sense of the term; that is to say, I show the depths of the human soul.” In making such a distinction between the quasi-scientific psyche and the spiritual reality of the human soul, Dostoevsky was showing himself to be, “in his own way, a metaphysician”. Once this is understood, we can understand his novels as invitations to the “spiritual adventure to which he summons us”. In this light, we might be reminded of the words of G. K. Chesterton. “An adventure is only an inconvenience rightly considered,” Chesterton wrote. “An inconvenience is only an adventure wrongly considered.” Although the juxtaposition of Chesterton’s paradoxical wit and whimsy might seem to sit a little uncomfortably beside Dostoevsky’s dark and doom-laden novels, if we see “inconvenience” as a soft euphemism for “suffering”, we can see that the Russian’s “spiritual adventures” are informed by this Chestertonian understanding of the connection between suffering and the adventure of life. An adventure is only suffering rightly considered, Dostoevsky might say of his own work. It is not the suffering itself that purifies or crushes the soul but our response to it.

Perhaps the greatest proof of Dostoevsky’s stature as a genius is his enduring relevance and perhaps perennial pertinence. “As the years go by, Dostoevsky grows in stature,” de Lubac writes. “The novelist no longer seems merely a psychologist and a metaphysician; he has the look of a prophet.” Like Shakespeare (and misquoting Jonson), Dostoevsky is not of an age but for all ages.

We will conclude this brief appraisal of Dostoevsky’s stature as a prophet with Henri de Lubac’s distillation of Dostoevsky’s importance to our own times:

Yes, Dostoevsky was a prophet: because he not only revealed to man the depths that are in him but opened up fresh ones for him, giving him, as it were, a new dimension; because, in this way, he foreshadowed a new state of humanity (that is to say, he heralded it by giving a preview of it); because in him the crisis of our modern world was concentrated into a spearhead and reduced to its quintessence; and because there is the vital adumbration of a solution there, a light-fringed cloud for our present journey through the wilderness.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

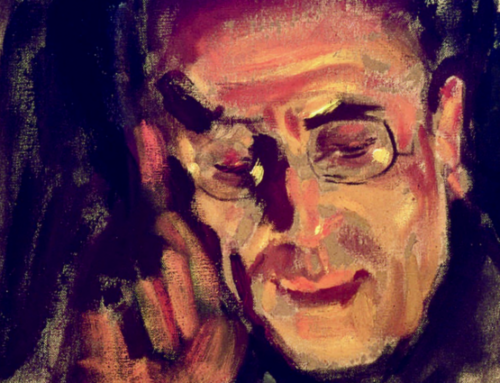

The featured image is “Portrait of Fedor Dostoyevsky” (1872) by Vasily Perov, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Yes I do believe it that Dostoyevsky was a prophet, his words is meaningful for everybody with any culture. I use word (culture) because it’s contents every religion, every language, every race, ……

In my opinion he was much much more greater than Shakespeare. None of novelists never ever could reach to Dostoyevsky level.

He was great writer , great philosopher, great psychologist, great ethnologists, he was great analysis of human behavior, interpreter women behavior and attitudes.

Yes he was different really great man on our planet.

Now in my early 70’s, I’ve studying and pondering Dostoevky for half a century now. In this timely and well-reflected article, I keep coming back and beyond to the word, prophet-prophetic. It is our alarmingly urgent business of life now to recreate an early 21st LANGUAGE of renewal and meaning of ‘this universal word, prophet, and what this sacred landscape nurtures for recognizing and preserving the prophetic. In any age, the prophet carries and sees through reality with his/ her old ancient eyes of wisdom. It is this age now that dedperately needs to HEAR and experience this new language…as if for the first time.