Even though President James Monroe could not fix the economy or dismiss the Missouri question, he could certainly distract the nation from its problems. In his second inaugural address, he gleefully announced a new target for American anger: The British were not allowing free trade between the United States and the English-occupied West Indies.

Whatever his best intentions or desire for republican virtue, James Monroe’s first administration had not gone as smoothly as one might have wished. Most specifically, as he might have wished! However deep the “Era of Good Feelings” might have been in 1817, when he took the oath of office, the great depression and the desire of Missouri to enter the Union as a slave state in 1819 shattered the illusion of a harmonious nation. Not only were thousands upon thousands of people financially desperate, but the debates surrounding Missouri’s admittance as a state ripped the Union apart along sectional lines. Senator Rufus King of New York spoke for many when he asserted:

Whatever his best intentions or desire for republican virtue, James Monroe’s first administration had not gone as smoothly as one might have wished. Most specifically, as he might have wished! However deep the “Era of Good Feelings” might have been in 1817, when he took the oath of office, the great depression and the desire of Missouri to enter the Union as a slave state in 1819 shattered the illusion of a harmonious nation. Not only were thousands upon thousands of people financially desperate, but the debates surrounding Missouri’s admittance as a state ripped the Union apart along sectional lines. Senator Rufus King of New York spoke for many when he asserted:

If Missouri, and the other states that may be formed to the west of the river Mississippi, are permitted to introduce and establish slavery, the repose, if not the security of the union may be endangered; all the states south of the river Ohio and west of Pennsylvania and Delaware, will be peopled with slaves, and the establishment of new states west of the river Mississippi, will serve to extend slavery instead of freedom over that boundless region. . . . if, instead of freedom, slavery is to prevail, and spread as we extend our dominion, can any reflecting man fail to see the necessity of giving to the general government greater powers; to enable it to afford the protection that will be demanded of it: powers that will be difficult to control, and which may prove fatal to the public liberties.

Admittance of Missouri as a slave state was, in every way possible, a complete denial of the spirit of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, King believed.

A native Virginian, President Monroe wanted nothing more than for the issue simply to go away. Even though Monroe could not fix the economy or dismiss the Missouri question, he could certainly distract the nation from its problems. In his second inaugural address, he gleefully announced a new (well, renewed) target for American anger: The British were not allowing free trade between the United States and the English-occupied West Indies. “No agreement has yet been entered into respecting the commerce between the United States and the British dominions in the West Indies and on this continent,” the president noted. “The restraints imposed on that commerce by Great Britain, and reciprocated by the United States on a principle of defense, continue still in force.”

Whatever British intentions were, they were almost certainly not meant to be hostile. After nearly twenty years of constant war—hot and cold—with France, Britain’s trade policy was a mess and in shambles, incoherent and without direction. Some—mostly the old guard—in Britain wanted to reestablish the empire as it had come together around 1774, complete with massive sea power (which it already possessed), colonial exploitation of resources, and established monopolies given to favored corporations. A younger set of British, mostly entrepreneurs and small businessmen, saw free trade with the United States, however, as the best and most secure policy for the United Kingdom. In the spring of 1820, they called—through petition—for almost complete free trade between the U.S. and the U.K.

In principle, much to the surprise of everyone, the House of Lords agreed with the petitioners.

There is no country more interested than England is, that the distress of America should cease, and that she should be enabled to continue that rapid progress which has been for the time being interrupted; for, of all the powers on the face of the earth, America is the one whose increasing population and immense territory furnish the best prospect for British produce and manufactures. Everybody, therefore, who wishes prosperity to England, must wish prosperity to America. . . . My Lords, we are now in a situation in which it is impossible for us, or any nation, but the United States of America to act unreservedly on the principle of unrestricted trade. The commercial regulation of the European world have been long established, and cannot suddenly be departed from.[1]

Being the younger country, though, the United States had to make the first move toward complete free trade.

When the United States failed to take the hint—mostly due to the personal views of one of America’s most powerful personalities, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams—the British offered a sort of peace/trade offering with its “American Trade Act,” in 1822, calling for a mutual de-escalation of tariffs. That is, if the Americans lowered its tariffs, the British would do the same.

Concerned with the chaotic state of American industry in the wake of the 1819 depression, the Monroe Administration as a whole was far more concerned with problems at home than problems with British trade.

John Quincy Adams held more specific views about and concerns regarding the British, though, few of them favorable. While Quincy Adams was not opposed to free trade as a policy per se (he knew his Burke and Adams Smith well), he was much more interested in outmaneuvering Britain in foreign affairs. Quincy Adams was willing, for example, to share custody over Oregon, but he wanted British influence to end elsewhere in the New World. Certainly, Quincy Adams said as much to the British, directly and indirectly. In no way, shape, or form, did Quincy Adams want Britain to nudge the Americas in one direction or another regarding slavery, the most divisive issue of the moment. Given that Americans were already economically depressed, their patriotism might be near the faltering point, especially when the British pushed too hard. “There the boundary is marked, and we have no disposition to encroach upon it,” Quincy Adams told his British counterpart, as they looked at a map of the Oregon Territory. “Keep what is yours, but leave the rest of the continent to us.”[2].

What neither America nor Britain could know at the time, though, was that post-Napoleonic continental Europe was deeply concerned about the future of the New World and ready to act upon those concerns. It was almost ready to impose its own designs upon the Western Hemisphere, and neither Britain nor the United States would allow that.

This essay was first published here in May 2020.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics as we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Notes:

[1] Quoted in George Dangerfield, Awakening, 153.

[2] Quoted in Dangerfield, Awakening, 167.

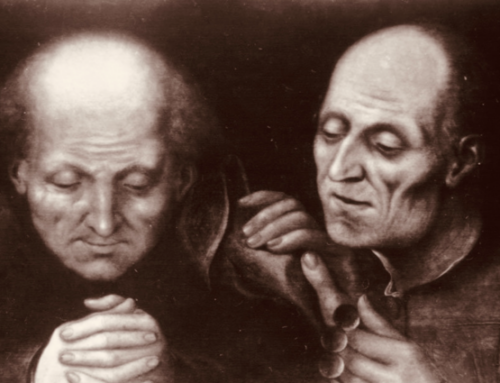

The featured image is a detail from “The Birth of the Monroe Doctrine” (1912) by Clyde O. DeLand (1872-1947) and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Thank you. Very good.

This fine article reads as a short story of exchanged hand, and leaves the reader at the point of outmost suspense: Europe (far far prior to even a concept of EU :)) aims to act in the New World, pushing GB and the USA towards each other despite disagreements! A sequel?