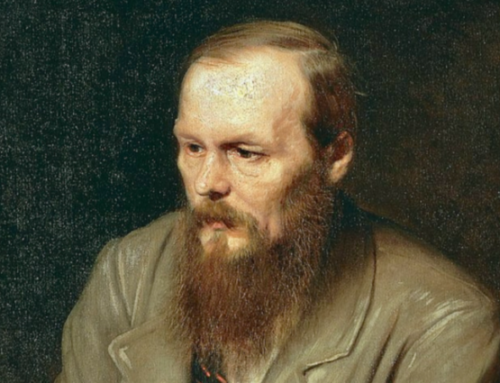

I know of no more comprehensive and reflective summary of conservatism than Sir Roger Scruton’s “Conservatism: An Invitation to the Great Tradition.” We should not expect conservative establishmentarians on either side of the Atlantic to pay it much heed, though, for the author has now been pushed into the ranks of the untouchables.

Conservatism: An Invitation to the Great Tradition, by Sir Roger Scruton (176 pages, All Points Books, 2018)

In the pantheon of science few figures merit a more honored position than does Antoine Lavoisier. Lavoisier almost singlehandedly overturned the idea that heat is a substance released by burning and friction, and developed combustion theory as an alternative; he set forth the law of conservation of matter; he laid the groundwork for the eventual establishment of the periodic table. By themselves such discoveries would confer an enduring reputation, yet even more important was Lavoisier’s systematic practice of data collection, which helped establish the modern scientific method. On the purely practical side his efforts to boost agricultural productivity and improve conditions in French hospitals and prisons offer a paradigm for the application of science to the lives of ordinary people.

In the pantheon of science few figures merit a more honored position than does Antoine Lavoisier. Lavoisier almost singlehandedly overturned the idea that heat is a substance released by burning and friction, and developed combustion theory as an alternative; he set forth the law of conservation of matter; he laid the groundwork for the eventual establishment of the periodic table. By themselves such discoveries would confer an enduring reputation, yet even more important was Lavoisier’s systematic practice of data collection, which helped establish the modern scientific method. On the purely practical side his efforts to boost agricultural productivity and improve conditions in French hospitals and prisons offer a paradigm for the application of science to the lives of ordinary people.

Neither Lavoisier’s extraordinary scientific achievements, nor his civic and humanitarian service, nor even his impeccable credentials as a man of the moderate left shielded him from the insanity of the Reign of Terror, however. In 1794, a revolutionary tribunal condemned the father of chemistry as an enemy of the people, and the first mortal head to imagine oxygen rolled its way into the executioner’s basket. That atrocities like Lavoisier’s judicial murder have been allowed to fade into obscurity tells us quite a bit about the state of the establishment right, which devotes too much time to earning leftist approval and too little time to addressing the myriad crimes perpetrated by leftists in the name of Equality. If we are foolish enough to reply upon Republican talking-heads, the egalitarian war on science, civilization, and human nature will never be checked.

There are honorable exceptions to the general rule of amnesia, though, and Sir Roger Scruton is one of them. At the very least Sir Roger is not to blame for the general public’s ignorance of the Revolution, for whether writing about the environment, music, or God, the English philosopher never fails to acknowledge his debt to the statesman Edmund Burke, arch-nemesis of the Jacobins and one of the co-founders of the conservative tradition. Even if conservative populism represents an attitude and outlook quite different from the Burkean strain, the author of Conservatism declines to join NeverTrumpers pining for the supposedly golden days of Bush II, instead seeing in the tectonic shift of 2016 an excellent opportunity for conservatives to reexamine their roots and do some heavy thinking. The long-term survival of Western culture depends in part upon how many other conservatives have the nerve to follow his lead.

Following Burke’s “complex, unsystematic but highly illuminating account of custom, tradition, and civil association,” Sir Roger affirms that the “binding principle” of society

is not contract but something more akin to trusteeship. It is a shared inheritance for the sake of which we learn to circumscribe our demands, to see our own place in things as part of a continuous chain of giving and receiving, and to recognise that the good things we inherit are not ours to spoil but ours to safeguard for our dependents. There is a line of obligation that connects us to those who gave us what we have; and our concern for the future is an extension of that line. . . Concern for future generations is a non-specific outgrowth of gratitude. It does not calculate, because it shouldn’t and can’t.

Here it becomes clear just how radical Burkean conservatism is, in the contemporary context—or, to examine the matter from the other end, it becomes clear that the underlying inspiration for the liberal project is man’s repudiation of his humanity. While “localist” liberals like to talk about neighborliness, for instance, and some of them may well practice it, anyone who thinks lucidly and coldly about the implications of leftist ideology will admit that “love thy neighbor” is, if taken seriously, every bit as “fascist” as a MAGA hat, if not more so.

Even as liberals and pseudo-conservatives alike ignore the destructive effects of runaway inclusiveness upon religion and culture, Sir Roger points out that such destruction is a feature of the inclusive regime, not a bug:

Rousseau’s social contract begins from an assembly of abstract individuals, who are without ties or attachments, and who have nothing to guide their social conduct other than the agreements that they can make with their fellows. This picture of society was shared too by the revolutionaries, for whom the old order was to be pulled down in its entirety, so that people could start again with nothing to guide them save their own free choice. But social beings are not like that, as Burke insisted. Societies are by their nature exclusive, establishing privileges and benefits that are offered only to the insider, and that cannot be freely bestowed on all comers without sacrificing the trust on which social harmony depends.

Whether we speak of pastor and flock, parent and child, or neighbor and neighbor, human relationships require a certain measure of focused intimacy, millions of Facebook “friendships” notwithstanding. So limits must necessarily be set upon inclusivity if future generations are to enjoy a recognizably human order.

Although Sir Roger emphasizes the Burkean variety of conservatism, he also introduces the unfamiliar reader to other strands, such as the French counter-revolution, the Hegelian right, and the agrarianism of the American South. Where Francois Rene de Chateaubriand highlighted the debt civilization owes to the Faith, as well as the adventurous, romantic, and aesthetic dimensions of Christianity, his fellow Francophone Joseph de Maistre argued that “the events of the Terror were literally satanic, re-enacting the revolt of the fallen angels, and displaying what ensues when human beings reject the idea of authority, and imagine themselves capable of discovering a new form of government in the freedom from government.” As for Hegel, if Sir Roger’s reading of the notoriously opaque The Philosophy of Right is accurate then Hegel’s initially revolutionary theory “evolved into the most systematic presentation that we have of the conservative vision of political order,” a presentation whereby detached Kantian universal ideals are balanced with “the historical attachments of real moral agents.” Turning to Warren, Tate, and their colleagues, Sir Roger recognizes the Vanderbilt Twelve as America’s first culturally-conservative intellectuals, and clearly appreciates their warning that high-speed, Twentieth-Century living “had detached Americans so completely from the soil that they were no longer at home in their own country.”

Although Sir Roger emphasizes the Burkean variety of conservatism, he also introduces the unfamiliar reader to other strands, such as the French counter-revolution, the Hegelian right, and the agrarianism of the American South. Where Francois Rene de Chateaubriand highlighted the debt civilization owes to the Faith, as well as the adventurous, romantic, and aesthetic dimensions of Christianity, his fellow Francophone Joseph de Maistre argued that “the events of the Terror were literally satanic, re-enacting the revolt of the fallen angels, and displaying what ensues when human beings reject the idea of authority, and imagine themselves capable of discovering a new form of government in the freedom from government.” As for Hegel, if Sir Roger’s reading of the notoriously opaque The Philosophy of Right is accurate then Hegel’s initially revolutionary theory “evolved into the most systematic presentation that we have of the conservative vision of political order,” a presentation whereby detached Kantian universal ideals are balanced with “the historical attachments of real moral agents.” Turning to Warren, Tate, and their colleagues, Sir Roger recognizes the Vanderbilt Twelve as America’s first culturally-conservative intellectuals, and clearly appreciates their warning that high-speed, Twentieth-Century living “had detached Americans so completely from the soil that they were no longer at home in their own country.”

To be sure, discerning readers are liable to raise their eyebrows at a few points. For instance, Sir Roger fails to mention the damage done to conservative thought by William F. Buckley’s respectable sanitizing of it. And this reviewer is of the opinion that Sir Roger goes much too easy upon Austrian libertarianism and Straussianism, given that the former movement embraces precisely the liberal individualism the conservative school was founded to confront, while the latter not only embraces egalitarianism uncritically but got to where it is in part by inciting leftist hatchet jobs upon the Old Right. Of course, Sir Roger is correct to note that in some circumstances conservatives might make common cause against socialism alongside libertarians, or even alongside a certain kind of neoconservative. But so what? It is just as true that conservatives could make common cause with a certain kind of leftist against the cultural and environmental depredations of global capitalism. At any rate, at a more conceptual level, by the end of the book we are still left wondering whether “conservatism” and “the right-wing” are entirely synonymous, and how our specific religious commitments might intersect with either.

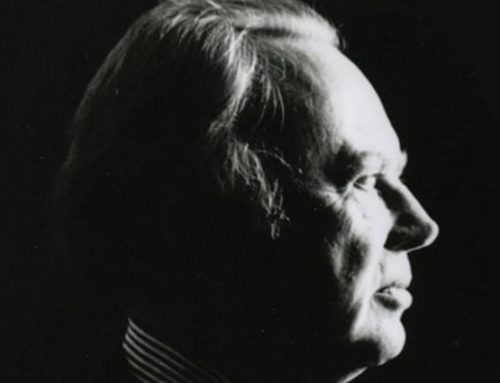

Still, when all is said and done I know of no more comprehensive and reflective summary of conservatism than Sir Roger Scruton’s. We should not expect conservative establishmentarians on either side of the Atlantic to pay it much heed, though, for the author has now been pushed into the ranks of the untouchables. During an interview conducted by a journalist from The New Statesman some time back, the English philosopher strayed from the safely obscure world of ideas to comment about current events, and so has been tagged as a “homophobe”—meaning he recognizes a natural purpose for sexuality—an “anti-Semite”—meaning he has noticed and objects to George Soros’s war upon Christian Europe—and a “racist”—meaning he frowns upon the policies of the Chinese government. Labour Party witch-hunters soon rallied on Twitter, and thus was Sir Roger booted from his advisory post with the United Kingdom’s “Building Better, Building Beautiful” commission. Apparatchiks worried about Sir Roger having a platform whereby to interfere with their dystopian urban planning can thus breathe easier: The racist conspiracy to beautify England has been thwarted—for now, at least.

Rather than commiserate with the dissident author of Conservatism maybe we should instead congratulate him, for at this point getting purged by the liberal regime is itself a mark of distinction, not shame. Getting purged nowadays means not that one is incompetent, but merely that one is not a total coward, fit only for finding new ways to regurgitate comically ossified clichés about equality and tolerance. True, Sir Roger is now persona non grata for many of the movers and shakers of British politics. Yet these movers and shakers are the spiritual cousins of Lavoisier’s murderers, the same lot who were too busy combating “xenophobia” to notice that an immigrant gang in Rotherham was freely abducting and molesting children. Really, what worth resides in the honors conferred by such people?

This essay was first published here in May 2019.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics as we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is a photo of Sir Roger Scruton, courtesy of his website.

Fine review of the latest from the leading conservative intellectual today.

Having read this book, I concur.

But, about history — it has a way of eventually defeating the ideologues who suppress everything not in accord with their narrow and myopic vision of Utopia.

Sir Roger will be vindicated.

I agree with the article, above all the remark that Sir Roger’s sacking is a medal rather than a sign of dishonour on him. But I do not believe that Sir Roger “strayed from the safely obscure world of ideas to comment about current events” just during the interview conducted by little George Eaton. I have heard a lot of Sir Roger’s lectures and read a lot of articles: he always tackles problems that concern political, moral and practical life of our days.

Thank you