When I was a child, my mother would regularly put my brothers and me to sleep by playing Fulton Sheen talks on tape and (later) on CD. I remember marveling first at the man’s voice, its weathered timbre and solemn cadence and massive fluctuations in volume. What held my attention next were the stories: stories of souls saved and souls lost and souls still hanging in the balance, with an occasional humorous story thrown in for comic relief. But what finally made Fulton Sheen my lifetime mentor were his ideas—his beautiful, crystalline, elemental articulations of Catholic doctrine and Catholic morality.

When I was a child, my mother would regularly put my brothers and me to sleep by playing Fulton Sheen talks on tape and (later) on CD. I remember marveling first at the man’s voice, its weathered timbre and solemn cadence and massive fluctuations in volume. What held my attention next were the stories: stories of souls saved and souls lost and souls still hanging in the balance, with an occasional humorous story thrown in for comic relief. But what finally made Fulton Sheen my lifetime mentor were his ideas—his beautiful, crystalline, elemental articulations of Catholic doctrine and Catholic morality.

Later on, when I got my first teaching job (about fifteen years ago now), I simply wouldn’t give a lecture on any topic whatsoever without looking to see if Sheen had a talk on the subject that I could listen to first. And, of course, he had talks on nearly everything. Even so there were a handful of themes that surfaced over and over whenever he spoke and whenever he put pen to paper. These five themes were the Eucharist, the Cross, the Holy Hour, Mary, and Sin. He spoke on these topics so much that I came to recognize not only the ideas, but even the formulations he used to express them. Sheen never minded repeating himself, plagiarizing his own best phrases across different works. If there was a point to be made, he made it, reiterated it, drove it home tirelessly over decades for the conversion and edification of his listeners.

Many of these classic Sheen insights on the Eucharist, the Cross, the Holy Hour, Mary, and Sin have been gathered into the anthology recently published by Sophia: Lord, Teach us to Pray. This volume embodies the heart of Sheen’s message, the essence of what he wanted to say, and the fruit he hoped that message would bear in his audience. And in addition to characteristic Sheen themes, this book conveys the characteristic elements of Sheen’s style.

He loved to insert poetry into his teaching and exhortation, and many of his favorite verses enter into this compilation. (Perhaps none is more lovely than St. Robert Southwell’s metaphor for the Incarnation: “The bird that built the nest is hatched therein.”)

One of my favorite Sheen traits, one he shares with the greatest theologians, is his delight in correlating the discrete parts on one aspect of the faith with the discrete parts of another. For instance, in Lord, Teach us to Pray, he lines up the seven last words from the cross with the seven parts of the Our Father and the seven parts of the mass (as it was at the time of his writing). This means that when we pray the Confiteor, for instance, we can imagine the crucified Christ invoking the Father’s forgiveness, and when we pray “Give us this day our daily bread,” we can link our wants and needs to the Lord who said “I thirst.”

Sections of the book are dedicated to brief meditations, many of which have all the force of timeless epigrams. Consider the moral and eschatological elegance, for example, of the following formula:

Love without pain is heaven.

Love with pain is purgatory.

Pain without love is hell.

Sheen never went long in writing or speaking without including Scripture. I’ll select just one passage, glaringly applicable to our present situation, from this volume: “The Breviary, which priests read daily, offers praise to Judas Maccabeus, who refused to surrender to superior enemy forces and died saying: ‘God forbid we should . . . flee away from them; but if our time be come, let us die manfully for our brethren, and leave no cause to question our honor’” (see 1 Macc. 9:10).

But I would suggest that the most valuable section of this new compilation is its inclusion of Sheen’s discussion on the Holy Hour—why to pray it and how to pray it. One of the arguments he gives on behalf of regular meditation is that it “keeps us from seeking an external escape from our worries and miseries. When difficulties arise, when nerves are made taut . . . there is always a danger that we may look outwards, as the Israelites did, for release.” But only by seeking God above and Christ within—only in prayer—will we find the solution to any ultimate problem. Only in prayer is peace.

This insistence on the Holy Hour was perhaps the greatest contribution of a great man. Fulton Sheen was many wonderful things: a priest, bishop, scholar, apologist, catechist, university professor, television star, retreat-preacher, supporter of foreign missions, and embracer of lepers. But most importantly, he was a man of prayer. It is in that more than in anything else that we can learn, in this book and elsewhere, from Bishop Sheen.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

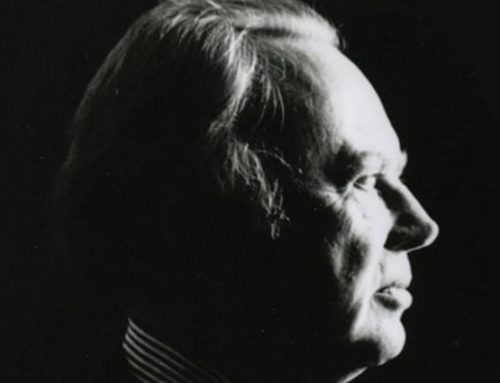

The featured image is a photo of Fulton Sheen (1956) and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Leave A Comment