So, you’re attracted to imaginative conservatism, and you’re wondering how such a school of thought came about. The roots, to be sure, are planted firmly in the first half of the twentieth century as a number of diverse thinkers strove to fight populism and progressivism (left and right, gentle and severe) in all their myriad forms. While there are thousands of books yet to be written and devoured, here are ten that helped shape the movement.

Irving Babbitt might not be the best-remembered conservative, but he was a critical figure in the movement. Along with Paul Elmer More, Babbitt founded imaginative conservatism. His 1919 book, Romanticism and Rousseau, while not the easiest of reads, completely deconstructed the essence and the appearances of his great bête noire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau. As Babbitt explains (correctly or not), the Romanticism of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries took its inspiration from Rousseau’s flights of fancy. Later conservatives, such as Barfield, Dawson, and Kirk, while respecting Babbitt, took issue with him over this, but they still gave him all due respect and pride of position.

Irving Babbitt might not be the best-remembered conservative, but he was a critical figure in the movement. Along with Paul Elmer More, Babbitt founded imaginative conservatism. His 1919 book, Romanticism and Rousseau, while not the easiest of reads, completely deconstructed the essence and the appearances of his great bête noire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau. As Babbitt explains (correctly or not), the Romanticism of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries took its inspiration from Rousseau’s flights of fancy. Later conservatives, such as Barfield, Dawson, and Kirk, while respecting Babbitt, took issue with him over this, but they still gave him all due respect and pride of position.

Willa Cather’s greatest book—and, in some ways, given the subtle twist on the last page, the most deceptive—is her 1927 novel, Death Comes for the Archbishop. Ostensibly following the life of Archbishop Lamy as a young evangelist, the novel explores the most important questions of the human condition.

If one placed Owen Barfield’s Poetic Diction next to any one of Babbitt’s books, there might well be a matter/anti-matter explosion. Barfield is, unlike Babbitt, nothing if not utterly romantic. Barfield’s romanticism, though, is tied more deeply to the thought of Edmund Burke than to that of Rousseau. Originally written as his undergraduate Oxford capstone paper, Poetic Diction has never been out of print since it first appeared in 1928. However young Barfield was when he wrote it, Poetic Diction has all the earmarks—such as they are—of genius. He is original in his thought and engaging in his writing. His theory is that imagination is not just fancy, but actually comprises real, true, and objective things.

If one placed Owen Barfield’s Poetic Diction next to any one of Babbitt’s books, there might well be a matter/anti-matter explosion. Barfield is, unlike Babbitt, nothing if not utterly romantic. Barfield’s romanticism, though, is tied more deeply to the thought of Edmund Burke than to that of Rousseau. Originally written as his undergraduate Oxford capstone paper, Poetic Diction has never been out of print since it first appeared in 1928. However young Barfield was when he wrote it, Poetic Diction has all the earmarks—such as they are—of genius. He is original in his thought and engaging in his writing. His theory is that imagination is not just fancy, but actually comprises real, true, and objective things.

Paul Elmer More wrote Pages from an Oxford Diary on his deathbed. Truly. And it shows. In it, the great imaginative conservative reconsiders his life in light of his journey toward Christian orthodoxy. Though he never quite reached it, he apologized to God for having taken so many wrong turns in the world. The last two pages of the book might, quite simply, be one of the greatest notes to God ever penned—at least since the Martyrdom of Perpetua.

Dedicated to the British people in the midst of war, Christopher Dawson’s 1942 The Judgment of the Nations is everything a history book should be but rarely is. With lively prose and ceaselessly innovative ideas, Dawson considers the role of Providence in history and produces a twentieth-century version of St. Augustine’s City of God. Modern evils and totalitarianisms, he notes, are the results of the shallowness of liberalism and the wickedness of progressivism, each conspiring to make men nothing but cogs in a grinding machine.

Dedicated to the British people in the midst of war, Christopher Dawson’s 1942 The Judgment of the Nations is everything a history book should be but rarely is. With lively prose and ceaselessly innovative ideas, Dawson considers the role of Providence in history and produces a twentieth-century version of St. Augustine’s City of God. Modern evils and totalitarianisms, he notes, are the results of the shallowness of liberalism and the wickedness of progressivism, each conspiring to make men nothing but cogs in a grinding machine.

One of Dawson’s rivals for most imaginative British conservative was the greatest Christian apologist of the last century, C.S. Lewis. The two, not surprisingly, knew one another but were not friends. Regardless, Lewis is at his absolute best in Mere Christianity (1952). Indeed, the book is so good and so earnest and so honest that even devout Roman Catholics teach it as a form of catechism to their children. It is, at base, an examination of the Natural Law, a sort of sequel or companion to his more philosophical book, The Abolition of Man. To be fair, one should read both. To be really fair, one should read all of Lewis. If you need Lewis’s philosophy and theology in its most digestible form, read That Hideous Strength.

Though he would (and did) hate the label conservative and often mocked conservatives while cynically accepting money from their few institutions, in The New Science of Politics (1952), Eric Voegelin brilliantly traces the route of the ancient Christian heresy of Gnosticism to its modern forms as found, especially, in the fascist and communist varieties of modern progressivism. Much like Dawson, though in a less theological manner, Voegelin laments the corruption of ancient symbols and the modern machine that grinds and destroys all that it surveys. Voegelin is the only person on this list who was not an imaginative conservative, but he was an important—if often unwilling—ally.

In the same year, 1952, T.S. Eliot’s publisher compiled his Complete Poems and Plays, 1909-1950. While it’s not comprehensive, it is brilliant. It includes Eliot’s Dantesque trilogy of The Waste Land, Ash Wednesday, and The Four Quartets, and it also includes Eliot’s best play, Murder in the Cathedral. The greatest poet of our age, Eliot was truly conservative and truly imaginative.

In the spring of 1953, Russell Kirk published his dissertation-turned-magnum-opus, The Conservative Mind. It is, as it turns out, a romantic sequel to the works of Irving Babbitt. Looking at the world through twenty-nine different historical figures—from Edmund Burke and John Adams through the then still living T.S. Eliot—Kirk arrives at six tenets of conservatism, each of which shifts according to the time and place of a particular issue. For Kirk, conservatism reaches toward the transcendent but always is rooted in the particular. What connects the divine to the mundane? Imagination.

In the spring of 1953, Russell Kirk published his dissertation-turned-magnum-opus, The Conservative Mind. It is, as it turns out, a romantic sequel to the works of Irving Babbitt. Looking at the world through twenty-nine different historical figures—from Edmund Burke and John Adams through the then still living T.S. Eliot—Kirk arrives at six tenets of conservatism, each of which shifts according to the time and place of a particular issue. For Kirk, conservatism reaches toward the transcendent but always is rooted in the particular. What connects the divine to the mundane? Imagination.

Though it took him at least twelve years to write, J.R.R. Tolkien finally published The Lord of the Rings in 1954 and 1955. In terms of his politics, Tolkien was a conservative. In terms of his artistry, he was absolutely imaginative—in the best sense. He understood language and the human condition—though he wrote of Elves and Hobbits—as well as anyone since Dante, Virgil, and Homer. Indeed, The Lord of the Rings is best thought of as the greatest epic of the modern world, rivaled only by The Divine Comedy, The Aeneid, The Iliad, and The Odyssey of previous vast eras of Western civilization.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

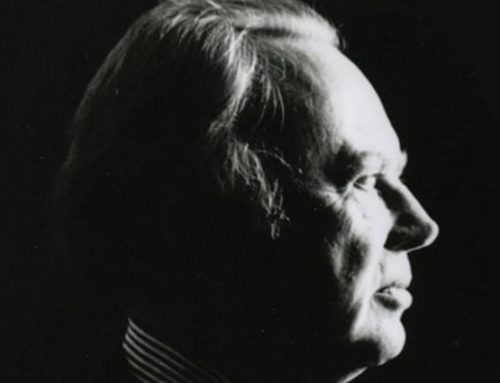

The featured image is courtesy of Unsplash.

That is a great list. Each of the works illuminates the life we have here in the modern world. Any one seeking to understand and work through the crisis of modernity would do well to follow Bradley Birzer’s lead on what to read. The books he includes are a kind of starting lineup for recovering one’s bearings.

Thanks, Andrew. These books have meant a great deal to me, spiritually as well as intellectually. Glad you agree!

Thank you. I think the last page of Death Comes for the Archbishop is one of the most unforgettable in all literature. Could someone please explain what is meant by the “subtle twist” on the page?

On You Tube there is a beautiful video about the friendship of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien titled “On the Power of Fiction,” by Timothy Keller.

Frances, thanks for the comments. I don’t want to give too much away, but when the Archbishop’s life flashes before his eyes, his life’s purpose WAS NOT want the reader would expect. The entire story is, beautifully, inverted.

While having read some of the works on this list, I have (alas) not read them all. Thanks Brad (sarcasm/not-sarcasm) for adding to my lengthy list of Books To Be Read Next Year.

However, your essay reminded me of an occasion when I responded to an acquaintance who (smugly) declared,” I am spiritual, not religious.” by informing him I was the opposite, as I could not conceive of a “spiritualism” that was noir firmly grounded in religious practice. (Which is a rant for another time.) “Imaginative Conservatism” is not some piece of tomfool flight of fancy. It is grounded in concrete examples, of which you have gracefully provided a few. (As you are well aware, there is a vast library of works which could have been mentioned.)

As I have been looking at this since Goldwater ran for President, my view may be a tad jaundiced, but it seems as though conservatism proper is not a linear or confided ideology but a broad and deep vein which may be mined for years without ever exhausting it. (Even if, by “conservatism proper”, I may be venturing into “No True Scotsman” ground.

David, I was born in 1967, so I missed Goldwater–but my mom was, very proudly, a Goldwater girl, and I grew up with great stories about him.

I would add Plato’s Republic, or any of his writings on love. Reading Plato is both informative and artfully poetic. A true gateway into the transcendent.

Agreed! I meant for this post only to focus on the first half of the twentieth century. I’ll do another post with the ten most important classics an imaginative conservative should read. Thanks for the comment!

“Regardless, Lewis is at his absolute best in Mere Christianity (1952). Indeed, the book is so good and so earnest and so honest that even devout Roman Catholics teach it as a form of catechism to their children. It is, at base, an examination of the Natural Law, a sort of sequel or companion to his more philosophical book, The Abolition of Man. To be fair, one should read both. To be really fair, one should read all of Lewis. If you need Lewis’s philosophy and theology in its most digestible form, read That Hideous Strength.” Agree 100%. I have probably read (or heard Mere Christianity) a dozen times. There is recording of Lewis doing it

Richard, I always love hearing from you. I’ve only read Mere Christianity three times. Here’s hoping for another 9!

Excellent list of important books everyone should read.

Thanks, Allen! Much appreciated.

“I’ll do another post with the ten most important classics an imaginative conservative should read. Thanks for the comment!”

Looking forward to it.

Great list! The last two pages of Pages from an Oxford Diary are incredible. Does anyone know of a translation for the last section (XXXIV) of the book? I believe it is in Greek.

re: Voegelin — I think it’s doubtful that someone can be much of an “ally” in politics if he doesn’t want to be.

re: Babbitt — Although it doesn’t (unlike Rousseau and Romanticism) shed much light on how imaginative conservatism came about, I would highly recommend Babbitt’s Democracy and Leadership. A great favorite of Russell Kirk’s, incidentally.