For all its levity, there is gravitas enough in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Its all-too-evident lesson is that those who succumb to the madness of erotic love, spurning chastity, will find themselves “enamored of an ass.”

Angels can fly because they take themselves lightly. So says G. K. Chesterton. On the other hand, as Chesterton also says, the devil falls by the force of his own gravity. Putting the matter less paradoxically and therefore more prosaically, we can say that angels and saints are good humoured because they have humility, whereas the devil and those who sympathize with him are prideful prigs who take themselves far too seriously. The former fly to heaven, carried by flights of angels to their rest; the latter make themselves gods of their own gollumized selves and have to live with themselves eternally. Nowhere is this shown more clearly than in The Great Divorce by C. S. Lewis, itself a diminutive echo of Dante’s divinest of comedies.

Angels can fly because they take themselves lightly. So says G. K. Chesterton. On the other hand, as Chesterton also says, the devil falls by the force of his own gravity. Putting the matter less paradoxically and therefore more prosaically, we can say that angels and saints are good humoured because they have humility, whereas the devil and those who sympathize with him are prideful prigs who take themselves far too seriously. The former fly to heaven, carried by flights of angels to their rest; the latter make themselves gods of their own gollumized selves and have to live with themselves eternally. Nowhere is this shown more clearly than in The Great Divorce by C. S. Lewis, itself a diminutive echo of Dante’s divinest of comedies.

These two types or archetypes can also be seen in the works of William Shakespeare. His comedies are full of the levitas which takes itself lightly, whereas his tragedies are full of the gravitas of those who take themselves far too seriously. This is, however, only part of the picture. The divine and the devilish dance and sing throughout each of the plays, comic and tragic alike. The levitas of his comedies is seasoned with the gravitas of sin, and the gravitas of the tragedies is lightened with the levitas of humour and enlightened by the presence of virtue.

Macbeth begins by taking himself far too seriously and falls into a state of suicidal despair in which he judges life itself as nothing but idiocy signifying nothing. “Nothing again nothing,” laments T. S. Eliot in The Waste Land. “Do you know nothing? Do you see nothing? Do you remember ‘Nothing’?” Macbeth is left with nothing. His quest for self-empowerment has left him impotent, not merely politically but philosophically. He is nothing, not merely physically but metaphysically. He is annihilated by the nihilism which he has embraced. Like the devil, he has taken himself far too seriously and has fallen by the force of his own gravity into the bottomless pit of the hell he has made of himself and for himself.

Hamlet, on the other hand, is the anti-Macbeth. He begins in the slough of despond, tempted to despair and to the suicide which is its cankered fruit. He ends, through a process of reasoned circumspection, with the acceptance that the “readiness is all” and with the words of the Gospel as his guide. He shows the “no greater love” that is the laying down of one’s life for one’s friends. It is no wonder that his faithful companion, Horatio, prays that flights of angels should sing the self-sacrificial victim to his rest.

Nowhere is angelic levitas and demonic gravitas more evocatively present in Shakespeare’s plays than in his treatment of the two types of love, caritas and eros. The former is rational, rooted in the rational choice to lay down our lives self-sacrificially for the beloved, even if the beloved is our enemy. Such love governs emotion and is not governed by it. The latter is irrational, rooted in the heart or the loins, and is often headless because it is heedless of the demands of virtue.

Numerous examples could be given of Shakespeare’s engagement with these two mutually antagonistic types of love but we’ll limit ourselves to looking at two very different plays written at around the same time. Romeo and Juliet and A Midsummer Night’s Dream were both probably written in late 1595 or possibly early 1596. Although ostensibly very different, the theme of both plays is the meaning and nature of love.

For Romeo, love is anything but rational. On the contrary it is “madness”:

Love is a smoke made with the fume of sighs;

Being purged, a fire sparkling in lovers’ eyes;

Being vexed, a sea nourished with loving tears.

What is it else? A madness most discreet,

A choking gall, and a preserving sweet. (1.1.197-201)

For Juliet, love is a blindness which prefers the darkness to the light. “If love be blind,” she says, “it best agrees with night.”

As for the dispassionate voice of the Chorus, which speaks, one suspects, with the voice of the playwright himself, it proclaims that there is no difference between Romeo’s obsessively unhealthy love for Rosaline and the love for Juliet which replaces it:

Now old desire doth in his deathbed lie,

And young affection gapes to be his heir.

That fair for which love groaned for and would die,

With tender Juliet matched is now not fair.

Now Romeo is beloved and loves again,

Alike bewitchèd by the charm of looks … (2.1.1-6)

The voice of the Chorus, being impartial and aloof, and therefore closest to the narrative voice of the playwright, makes no distinction between the nature of Romeo’s love for Rosaline and that which he has for Juliet. The “old desire” for Rosaline may be dead but the “young affection” for Juliet desires eagerly to be “his heir”. One “love” has simply been replaced by another in its likeness. Romeo is “beloved and loves again, / Alike bewitchèd by the charm of looks”. Again, no distinction is made between the earlier love and its heir. Indeed, the Chorus seems to be suggesting that there is no distinction. Romeo simply “loves again”. He has not spurned false love for true, but merely loves both women in the same way. In this sense the phrase “alike bewitchèd” seems to have a double-meaning. Romeo and Juliet are “alike bewitchèd”, i.e. bewitched by each other, but Romeo is also “alike bewitchèd” in that he was bewitched by Rosaline and Juliet alike. In both cases, he is bewitched by physical beauty, by “the charm of looks”. And let’s not forget that the love between Romeo and Juliet can be nothing but skin-deep and purely physical at this stage. Romeo and Juliet do not know each other. They do not even know each other’s names. Romeo declares his “love” before he has even spoken a single word to his beloved. How can such love be anything but superficial, a bewitchment of the eye in erotic response to great physical beauty?

The connection between the tragedy of Romeo and Juliet and the comedy of A Midsummer Night’s Dream is made manifest in the famous “Queen Mab’s Speech” by Mercutio in the former play. Mercutio tells us that Mab, the queen of the fairies, “gallops night by night through lovers brains, and then they dream of love”. Mercutio’s words serve as a curtain-raiser to the play about fairies which Shakespeare is about to write or, if A Midsummer Night’s Dream was written first, a deferential nod to the play he had just written. Either way, these two plays, so different, the one marked by the gravitas of the lovers’ fatal fall and the other by the levitas of the lovers’ frolicsome folly, have the same theme in common. Both plays contrast rational Christian love with irrational erotic love.

The “magic” of the fairies in A Midsummer Night’s Dream appears to have less to do with any supernatural or elvish power than with the natural and biological power to be found in woodland herbs. The “love-at-first-sight” drug that has the power to make people love the first thing they see, causing chaos, is known as “Cupid’s flower”, whereas its antidote, which enables people to judge rationally in matters of love, is known as “Dian’s bud”. The allegory is clear enough. Diane is of course the goddess of chaste love, the love that Romeo specifically spurns: “Her vestal livery is but sick and green, And none but fools do wear it. Cast it off.”

Oberon, King of the Fairies, begs to differ with the feckless and reckless Romeo, who is addicted to “Cupid’s flower” and blinded by his abuse of it. “Dian’s bud o’er Cupid’s flower hath such force and blessèd power,” says Oberon, applying the blessed herb to his wife’s eyelids, that it serves as an antidote to the madness brought on by the aphrodisiac.

“Methought I was enamored of an ass,” says Titania, after the blessed herb of chaste love restores her reason and her sight.

For all its levity, there is gravitas enough in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Its all-too-evident lesson is that those who succumb to the madness of erotic love, spurning chastity, will find themselves “enamored of an ass”.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

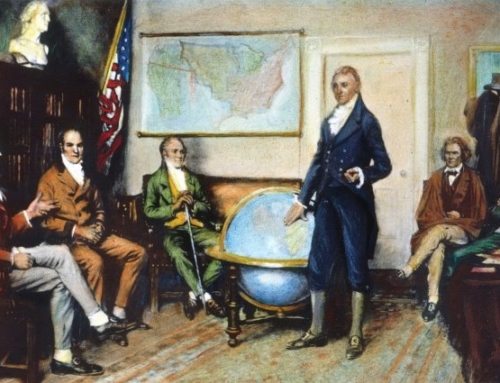

The featured image is “Scene from A Midsummer Night’s Dream” (between 1848 and 1851) by Edwin Landseer, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

As someone who never had the language to penetrate the beauty of Shakespeare’s works, these essays are a blessing. Thank you.

Love you Joe, but I still think Shakespeare’s presentation of the MARRIED Romeo & Juliet is an example of requited (two way) holy love, as opposed to the UNREQUITED (one way)”love” of Romeo for Rosaline. It’s madness if it’s obsessive, but Romeo and Juliet are both (equally) in love. The tragedy is that they create and live (ever so briefly) in that holy world which the outside world of Montagues and Capulets can’t seem to get to. They tragically die due to fate, stupidity, family wars, none of which are their fault.

I’ve never seen the play done as a “morality play” preaching against lust or “love at first sight”, or “sin”, though of course they tease about “sin” when they first meet.

I respect your opinion and I can see where you can read such things into the play, but I think of the play differently; I think more in line with the conventional interpretation. Perhaps that is the magic of Shakespeare.

I think at times I sort-a feel a bit of both thing. That Romeo and Juliet’s love is in many ways immature and unwise, but it’s kind of sympathetic because they are young and in an unusual situation. I read that in the early Irish penitentials the penance for irrational eroticism was a bit less for adolescents because of lessened maturity, etc. So this makes it tragic, rather than foolish or stupid, because ordinarily their youthful immaturity could get seasoned with time or guidance but they’re in a situation of feuding parents, etc so it instead ends in death. (That said there is a case of what seems to be legitimate “love at first sight” in music history with Felice and Boudleaux Bryant. They eloped five days after meeting and were together for over 40 years so it probably was something real.)

Mr. Pearce’s ongoing campaign against sympathy for Romeo (which I have read of elsewhere) strikes me as just bizarre. The play has been held up as the epitome of romantic tragedy, not because Romeo is a sexist pig and a shallow sensualist, but because he and Juliet have been struck by love (and, yes, desire) at first sight, in the old-fashioned way that people believed in 400+ years ago and still do. Sometimes it’s an illusion, but frequently it isn’t. And Shakespeare’s contemporaries certainly held to the old “eye-beams entwining” theory. Over the centuries that theory has diminished from solid science to something more emotional, but the star-crossed lovers have been embraced as sweet and sincere, and their tragic end regarded as the product of irrational hatred between long-term rival seats of territorial power, and not the product of selfish adolescent lust — even when the audiences came to the play with proper Victorian Protestant morals. With all due respect, Mr. Pearce, you have a strange bee in your bonnet on this subject, and it does you little credit.

In my experience, young students studying the play, who usually focus on the story and the content, tend to find the characters of Romeo and Juliet annoying and unsympathetic while Shakespeare professors, who usually focus on the beauty of the poetry, tend to find them sympathetic. If you ask me, a proper analysis of the play should take both interpretations into consideration as they’re both latent in the text.

I’m not really sure how A Midsummer Night’s Dream can be seen as having a pro-chastity message when the central disaster in it (Puck applying the love juice to Lysander instead of Demetrius) happens because of a character insisting on sexual boundaries. Lysander wants to sleep next to Hermia. She insists he maintain his distance. As a result, Puck mistakes them for Demetrius and Helena. I wouldn’t interpret the play as being pro-fornication either but calling it pro-chastity seems forced without more evidence.

Excellent analysis as always. It seems like there are a lot of commenters who believe in “love at first sight.” Personally I’ve never encountered it or met anyone who has. Plus, once this wears off is when the real living begins.