The Red Rose Revolution brought about by Princess Diana’s tragic death was a triumph of sentimentality over reality. In the intervening twenty-five years, that sentimentality has prevailed in England, sweeping away the sterling values that had been the hallmark of English character.

I am somewhat ashamed to admit that I have watched the most recent installment of the lavish royal soap opera The Crown. I reviewed earlier series here, here and here, and decided to watch the final series to see how the producers handled the dramatic events of the death of Diana, Princess of Wales.

I am somewhat ashamed to admit that I have watched the most recent installment of the lavish royal soap opera The Crown. I reviewed earlier series here, here and here, and decided to watch the final series to see how the producers handled the dramatic events of the death of Diana, Princess of Wales.

The series is billed as a drama based on historical events. That is a fair description, and viewers should not be deluded into thinking it is more than that. After all, Shakespeare himself was adept in adopting royal history and adapting it to his dramatic purposes. The main difference is that film replicates reality so much more effectively than a stage production. When we attend the theater we corporately and consciously suspend our disbelief. When we watch television it is easier and more tempting not to.

The first four episodes of season six deal with Princess Diana’s friendship with the Egyptian film producer Dodi Fayed, their doomed romance and tragic death. They also portray the stoic response of the rest of the royal family to Diana’s demise. Were the Royals really so coldhearted, devoted to duty, and dead-set on maintaining palace protocol in the face of such a public tragedy?

Peter Morgan, the writer of the series, already explored this tantalizingly complex drama in his film The Queen starring Helen Mirren. This time he plunges too explicitly into the quicksand of psychological motivations and recriminations, and does so with the cloying and annoying dramatic trick of Diana and Dodi’s ghosts having after life conversations with the Queen, Prince Charles, and Dodi’s dad, Mohammed Al Fayed.

It was too “on the nose.” A screen writer of Morgan’s intelligence and experience should have known better. While the writers, directors, and actors should be aware of deeper desires and hidden motivations, they should be kept below the surface—being revealed through actions and events, and allowing perceptive viewers to make the necessary connections through thoughtful observation and cathartic emotions, not through explicit statements.

Curiously, this explicit treatment of emotion connects with one of the underlying themes that the drama of Diana revealed. It is something I have dubbed “England’s Red Rose Revolution.” When Diana died in Paris, the royal family were on vacation at Balmoral Castle in the Scottish highlands. At one point in the film, Prince Charles (Dominic West) informs the Queen and Prince Philip about the huge surge of emotions pouring out across England while they are ensconced in Scotland.

We were living in England at the time, and I remember the astonishing outpouring of grief. Multitudes were in the streets, thronging royal palaces and laying oceans of floral tributes at their gates. As a former royal, Diana did not warrant a state funeral, and the first plans were for the Spencer family to hold a private funeral service.

Eventually a lavish state funeral took place in Westminster Abbey, replete with Elton John weeping as he sang a maudlin version of his elegy to Marilyn Monroe hastily re-written as a tribute to Diana. The massive crowds packed the streets of London were openly sobbing in scenes that were totally unprecedented.

What on earth was happening in the land of the Blitz Spirit and the stiff upper lip? In The Crown, the Prince Charles character called it a revolution. It was as if the English had bottled up all their emotion from two catastrophic world wars, the deprivations of the immediate post-war period, and the economic and political rumblings of the seventies and eighties. The Queen’s steady spirit and Margaret Thatcher’s strong backbone took them through, and the steely resolve of the English people seemed to hold steady. They could stand solid in any storm.

Meanwhile, Diana Princess of Wales became the figurehead of a new, kinder, tender-hearted England. She embraced AIDS victims, was a happy and hearty mother to her two adorable princes, and was the victim of a heartless and unfaithful husband. She wanted to be the “Queen of Hearts” and so won the hearts of the English. When she died, those hearts were broken and so was the solid, stoical, stiff English society. A dam was broken, and the flood of emotion was astonishing and disturbing.

It was a Red Rose Revolution because red roses are the archetypal symbol of sentimental romance. The facts of the matter are perhaps more sobering. While Diana was a tender-hearted, kind, and compassionate person, she was also an immature, manipulative, entitled, spoiled, and promiscuous woman. She may have been a good mother, but she was also a woman who displayed her amorous friendships not only to the public, but also before her own children. Her behavior was no worse than that of her husband and other royals and celebrities, but her carefully cultivated “shy Di” persona sheltered her from a harsher assessment of her behavior.

The Red Rose Revolution brought about by her tragic death was a triumph of sentimentality over reality. In the intervening twenty-five years, that sentimentality has prevailed in England, sweeping away the sterling values that had been the hallmark of English character.

The sentimentality that prevails in England today has taken the form of a kind of compulsive sensitivity to everyone’s feelings, but without any objective moral standard or authority. An easy tenderness accompanied by an aggressive tendency to prosecute anyone who appears, even slightly, to be “hateful” or “phobic” dominates the social conversation.

Flannery O’Connor famously quipped that “tenderness leads to the gas chambers.” Here’s why: The triumph of sentimentality is the triumph of subjective individual emotions over objective truth and values. Once sentimentality triumphs, the sentimentalist feels his own emotions to be good and therefore perceives himself as a good person for having those fine emotions.

What the sentimentalist overlooks is the fact that there are many kinds of emotions. While he is awash in the nice, sweet, tender-hearted, and compassionate emotions, he is blind to the emotions of rage, resentment, and revenge that also lurk in the human heart, and when those bitter emotions emerge (as they most certainly will), having already accepted that his emotions are worthy and virtuous, he accepts the ignoble emotions as also worthy and virtuous.

Furthermore, in his self-righteousness he will consider it his duty to act on those emotions, and if those emotions demand action against others who do not share those emotions he will take action against them—and that action is eventually the action to persecute, exclude, and ultimately eliminate the “enemy”.

The English successfully resisted the various Marxist revolutions that brought bloodshed, war, and disaster to Europe in the twentieth century. The stiff resolve of the English held firm. It is a historical co-incidence that just three months before the death of Diana, the leader of the Labor Party—Tony Blair—was elected as Prime Minister. The symbol of Blair’s leftist “New Labor” was a Red Rose.

Red had always been the color of the communist/socialist revolutionaries. The rose provided the oleaginous Mr Blair a sentimental symbol for the revolution that has transformed England, and Diana’s death was the earthquake that produced the tsunami of sentimentality that swept England into its present morass.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

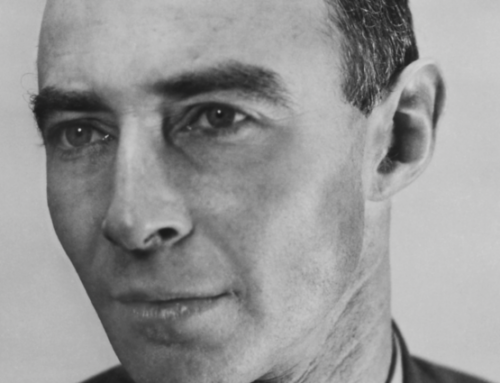

The featured image is a photograph of the “Royal Visit of Prince Charles and Princess Diana to Edmonton, Alberta – Welcoming Address by Premier Peter Lougheed at the Alberta Legislature, 30 June 1983.” This image has no known copyright restrictions, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Dear Fr. Dwight;

May Diana, Princess of Wales, requiescat in pace.

Regarding your article: Hear, hear!

Thank you,

I mean I sort of get it, but I think some of this kind of thing is a bit too much a fear of anything potentially feminine or childlike even if you quote a woman.

Gentle and kindness are not bad things so to a degree sentimentality isn’t either. America long had more sympathy to sentimentality than the Brits, but we became even less Leftist than them until very recently. And at least some of the Catholic mystics were willing to express intense emotions in public.

To me it’s more a variety of good or neutral things can become bad if they are ratcheted up to exclusion of all else. I think I get what she’s saying but “tenderness leads to the gas chambers” is a bit of an excessive thing to say. Yeah you need proper reason and sense, but if you have those allowing yourself tenderness or sentimentality I still think can be a good and comforting thing. For the Nazis they weaponized feeling sad about us disabled to get people into thinking it’s better for us to die than live our tragic lives. But even there the Nazis kind of failed, in the rare case of the German people rebelling their euthanasia program had to go underground. And I would guess some of their opponents were moved by their form of “excessive tenderness” to the disabled. (So okay I guess I’m saying that this one time O’Connor was pretty much just wrong.)

But then again I’m also not an Anglophile. I can admire the British resilience but their traditional coldness I don’t find admirable or all that Christian. (Jesus had public expressions of emotions and grief.)

Thomas R: The critique of sentimentalism is not of proper tenderness, but of sentimentality to the exclusion of rationality. The opposite extreme would be heretical in the other way: i.e. all head and no heart.

Yes, I remember the death of Lady Diana. As much as the event was a tragedy, the mass outpouring of grief was puzzling. Then, less than a week later, the death of Mother Teresa was received rather quietly. Even to me, a new and young Christian, the juxtaposition of the two seemed to indict our culture.

Father Longnecker: hear! hear! I see this sort of thing in orthodox Catholic endeavors: the people in charge assume their posts oblivious to conflicts of interest: parents on the school Board decding what fate awaits a teacher who has displeased their child etc. etc.: and when things look like a petty exercise of power rather than a judicious adherance to policy (which might not exist) those in charge want the benefit of the doubt that they have acted justlsy because “they’re Catholic” doing a Catholic thing; and I think it’s everywhere now: yes, Flannery was right. sentitmentality eventually leads to the gas chamber.

Thanks for the keen observations, Fr. L. You’ve helped me make sense of the over the top sentimentality regarding D’s life and death. <

A brilliant analysis of a phenomenon that has swept through not just England but the U.S. as well, and, I’m sure, other countries.

When Thomas R says “if you have those allowing yourself tenderness or sentimentality I still think can be a good and comforting thing,” I think he rather misses the point. Yes, of course, sentimentality is comforting to the sentimental. That’s who they are, and perhaps they are not capable of anything better.

The author is right on target in his critique of the emotion, however. One problem with it is excess. It is unmoored from a commensurate cause or grounding. Or as the author says, from reality. It is also narcissistic.

Sentiment, on the other hand, is the term we use for emotion anchored in reality. It is perfectly normal, healthy, and quintessentially human. To lack it is to be, in C. S. Lewis’, phrase, men [or women] without chests,” people “who act without trained emotions” (Abolition of Man).

The book by Lewis referenced above would in fact be another commentary on what can go seriously wrong when an ocean of sentimentality threatens to sweep over a society, no matter whether that ocean contains sweet or bitter water.

Oh okay.

Yeah there is a kind of irrational sentimentality that can also get kind of pushy or aggressive. Like expecting or demanding people grieve in some dramatic way even if that’s just not their temperament or how they do things. Or in the case of Diana being sentimental about someone you never really knew in a way you might not to someone more real to you.

(Then again romanticized imagery of female nobility might not be entirely new to the English. Queen Elizabeth I I remember reading somewhere encouraged excessive feelings about her as a replacement for some of the Marian piety of the Catholic age. To treat her or Princess Di as akin to Mother Mary would be beyond heresy into just weirdness, but maybe something a tiny bit like that happened anyway.)

If Queen Elizabeth I “encouraged excessive feelings about herself as a replacement for some of the [lost] Marian piety of the Catholic age,” it should not be surprising. Members of the royalty of that age, as well as ours, have done stranger things.

And as you say, affording either her or Princess Diana the same order of honor as the B.V.M. would be weird, or worse.

But on the basis of your comment and the article itself, it occurs to me that Princess Diana did in fact become a Mary for the secularists of the realm. (Realm should not be too tightly defined here.) The role of the B.V.M. in the Incarnation is for many of them, I suspect, viewed as a fairy tale, if contemplated at all. So, to replace what Christians believe happened, they are only too eager to confect a substitute, aided and abetted by the popular media and at least one pop crooner. Thus, Princess Diana = Queen of Hearts.

For some of us that development is understandable, given their orientation. It is also utterly bizarre.

However, was it T. S. Eliot who said in connection with Matthews Arnold’s lost faith, “Nothing in this world is a substitute for anything else”? The Christian realist knows this; the sentimentalist never will.

Thank you, Fr Longenecker, for taking a step back to gaze upon the gazing and giving it a good and thorough pondering!! Now I am going to be on the lookout for all the more examples of Sentimentalism without Truth. I think this is what defines most of our school programs, news stories, abortion narratives, trans-tales, and end of life death campaigns.

I wonder if there is any way that we could aim your truth magnifying glass to sweep across my beloved Ireland? A country that long held emotions and stories and pints and fights and public displays of sentiment… but yet held fast to Truth. Travails may have come, but was grounded and rooted. With the vote to enshrine abortion as a national right, the country seemed to sever that which kept it steady. And now is adrift.

It seems the stories we consume and proclaim because they have all the feels but none of the work of thinking, bring about our own demise. Thank you for your thought.