Those who read as Shakespeare wrote, seeing the facts in the light of the truth they serve, will be servants of that greater science animated by a love of wisdom (philosophy) and of the greatest of all sciences which leads to a knowledge of God (theology). Those who read reality in this way are never satisfied with the mere facts because they seek the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

One of the most beguiling of Chesterton’s aphorisms is his insistence that we should not put facts first but truth first. As with Christ’s paradoxical axiom that the first shall be last and the last shall be first, Chesterton’s paradox would appear to be blatantly self-contradictory and therefore patently absurd. Facts are true and the truth is a fact. Chesterton is, therefore, an (oxy)moron. Similarly, and blasphemously, the first is not last and the last is not first, which makes Christ an (oxy)moron also. The problem is not with the apparent oxymoronic nature of the paradoxes, however, but in the inability of the reader to see the paradoxical truth which transcends the mere literal “facts”. A paradox is an apparent contradiction that points to a deeper truth.

One of the most beguiling of Chesterton’s aphorisms is his insistence that we should not put facts first but truth first. As with Christ’s paradoxical axiom that the first shall be last and the last shall be first, Chesterton’s paradox would appear to be blatantly self-contradictory and therefore patently absurd. Facts are true and the truth is a fact. Chesterton is, therefore, an (oxy)moron. Similarly, and blasphemously, the first is not last and the last is not first, which makes Christ an (oxy)moron also. The problem is not with the apparent oxymoronic nature of the paradoxes, however, but in the inability of the reader to see the paradoxical truth which transcends the mere literal “facts”. A paradox is an apparent contradiction that points to a deeper truth.

Pride is putting ourselves first and others last. Love is putting others first and ourselves last. It is in this sense that the first shall be last, and the last first. He who puts himself first shall be last in the kingdom of heaven. He who puts himself last shall be first.

Facts, in the sense in which Chesterton uses the word in the aforementioned axiom, are literal whereas the truth is only accessible allegorically. Thus, for instance, we will not be understanding the Bible if we remain stuck with the facts and the facts alone. This must be insisted upon. Those who read the Bible only literally are not really reading it at all. As Thomas Aquinas reminds us, there are four levels of meaning in Scripture. The first level is the literal level, the facts being presented. Then there is the allegorical level, in which the Old Testament can only be understood in the light of the New Testament. Next is the moral level in which what we read is applicable to our own lives and situations, and those of our neighbours. Finally, there is the anagogical level of meaning in which what we read in the Bible relates to eternity in general and our own eternal destiny in particular. Since the literal level of meaning (the facts) is a means of pointing to deeper truths, we can say, with Chesterton, that we must not put facts first but truth first, in the sense that the former are the means by which the end is attained.

The foregoing is an explanatory preamble to the critical blindness of the so-called “scientific” approach to truth exemplified in a recent book, Death by Shakespeare by Kathryn Harkup, a British chemist who undertakes to explain what Shakespeare got wrong in his depiction of death in his plays. “He’s good at observation, but without necessarily understanding the science of what’s going on,” Dr. Harkup said in a recent talk at the Cheltenham Science Festival in Gloucestershire. “But he is not making a science documentary. He is entertaining his audience.” We might add that he is also telling the truth, as well as merely entertaining his audience, which means that he puts the scientific facts at the service of truth.

Take, for instance, the murder of Hamlet’s father. According to Dr. Harkup, the facts of his death display a lack of scientific knowledge on Shakespeare’s part which made his murder “unrealistic”:

Hamlet and the poisoning — I have big issues with this. If you want to get rid of your brother, don’t poison them by pouring stuff in their ear. That is a terrible idea. There’s not many blood vessels around that part of you. Your ear is protected with cartilage, thick skin, wax — getting the poison to be absorbed into the body properly to do the damage is not really going to work.

This is all very amusing, indicative of Dr. Harkup’s own commendable ability to entertain her audience and readership, but is she being fair to Shakespeare? Irrespective of whether he had a firm grasp of all the scientific facts with respect to the anatomy of the ear, he would surely have been aware that pouring poison into the ear is not a very efficient or effective way of killing people. People had been killing each other for thousands of years by the time that Shakespeare was writing Hamlet. He would presumably have been as aware as the rest of us that the ministering of poison to the ear was not a tried and tested method of killing someone. He chose this unusual method, using poetic licence and expecting his audience to suspend their disbelief, because the poisoning of the ear is a major theme of the whole play. It is the poisoning of the ear by lies and deception which is the main cause of death in the play. The ministering of poison to the ear is indeed deadly. It has killed millions of people in the past and will continue to kill millions of people in the future. Sin is the poison which manifests itself throughout Hamlet, of which the poisoning of Hamlet’s father was but a metaphor.

Another example that Dr. Harkup cites is that of Cleopatra. In Antony and Cleopatra, the Egyptian queen chooses an asp to end her life because its venom “kills and pains not” and will make her die “at once”. “She wants two things from this death,” Dr. Harkup explains. “She wants a painless death. And she wants to make an attractive corpse.”

Presuming that the asp was probably a cobra, considering that the action of the play is taking place in Egypt, Dr. Harkup explains that any death caused by a cobra bite would be very painful and would not be instant, nor would it leave the corpse looking especially attractive. This is all impeccably accurate in terms of the facts but is not a reflection of the truth that Shakespeare is conveying. The asp is nothing as mundane as a mere cobra or any other species of snake. It represents that other serpent which tempted Eve in the Garden.

Let’s look at the facts surrounding Cleopatra’s selfish act of self-destruction in order to see the deeper truth to which they point. She kills herself in spite of Caesar’s warning that he would kill her own children should she commit suicide. Her act of self-slaughter is, therefore, a slaughter of the innocents. She chooses a serpent as the means by which she will take her own life, connecting the play’s final scene to the Book of Genesis, because its venom “kills and pains not”. Cleopatra chooses her own comfort in death as she had chosen it in life. She is the antithesis of the Christian who is called to accept and embrace suffering by taking up his cross and following Christ. “Peace, peace!” she proclaims as she holds the serpent to her chest. “Dost thou not see my baby at my breast that sucks the nurse asleep?”

Lest we should fail to connect the fall of Cleopatra with the fall of Eve, Shakespeare has the Guard report that the serpent had left a trail of slime on “these fig leaves”, indicating clear proof of the means by which she had died. In making this final biblical allusion, we are invited to see Cleopatra as more than merely a tragic heroine from ancient history but as a representative of fallen Eve and, by extension, our representative also. She is an Everyman figure. She is who we are and who we are doomed to be if we will not accept the redemption offered by Christ.

Such emergent truths are the living splendour of Shakespeare’s works, transcending the literal level of meaning grounded in the mere facts of the plot.

Those who read as Shakespeare wrote, seeing the facts in the light of the truth they serve, will be servants of that greater science animated by a love of wisdom (philosophy) and of the greatest of all sciences which leads to a knowledge of God (theology). Those who read reality in this way are never satisfied with the mere facts because they seek the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

This essay was first published here in June 2022.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

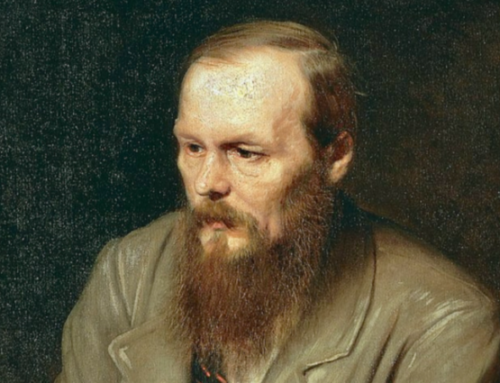

The featured image is the Chesterfield Portrait of William Shakespeare (c. 1679) by Pieter Borsseler, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Much in Shakespeare doesn’t make literal sense. In Ii of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” Theseus says that he and Hippolyta will wed on the night of the new moon; in Iii Peter Quince suggests there’ll be a full moon. In “Twelfth Night” Viola has no reason to masquerade as a young man — though a woman and traveling alone (her brother assumed dead), she has the protection of the Sea Captain and is in the domain of a duke who knew her father; nevertheless, had she not disguised herself, there would hardly have been a play. And toward the end of “Romeo and Juliet,” what Pearce refers to as “the mere facts of the plot” are so far-fetched that even my former ninth-graders considered them unbelievably unrealistic. Does one read or watch Shakespeare for believable realism? Hardly.

It is interesting to note that if “Hamlet” is, in fact, an allegory against Henry VIII having broken with Rome, having usurped the authority of the Church, and having “wedded” Church to State, a union too close, “incestuous”, then allegorically the poison poured into the King’s ear would have been heresy which spread “swift as quicksilver” during the Reformation and “tainted” the faithful. While the Church “slept”, failed to reform, the poison of heresy had spread.