It is the encounter with beauty, all-consuming beauty, the infinite, which directs the human soul back to God. The sky calls us up; the earth drags us down.

On December 2, 1805, the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte achieved his most spectacular victory at the Battle of Austerlitz against an allied army of Russians and Austrians. The battle is remembered for its brilliance and savagery and was immortalized in Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace. On the blood-stained slopes of the Pratzen Heights, Prince Andrei Bolkansky—wounded and looking up at the skies—gazes upon its immense beauty before he passes out. For the first time in the story Andrei puts aside his empty personal ambitions and allows the serenity around him lift him up to the heavens despite the chaos of a battle surrounding him.

On December 2, 1805, the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte achieved his most spectacular victory at the Battle of Austerlitz against an allied army of Russians and Austrians. The battle is remembered for its brilliance and savagery and was immortalized in Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace. On the blood-stained slopes of the Pratzen Heights, Prince Andrei Bolkansky—wounded and looking up at the skies—gazes upon its immense beauty before he passes out. For the first time in the story Andrei puts aside his empty personal ambitions and allows the serenity around him lift him up to the heavens despite the chaos of a battle surrounding him.

Prince Andrei is one of the many, and memorable, characters in Tolstoy’s epic. Rightly considered one of the greatest works of literature and the seminal Russian odyssey, Andrei stands in for Tolstoy, you, and me. The young prince seemingly has everything going for him. He is handsome. He comes from a wealthy and important family. He has a successful career as the aide-de-camp to Mikhail Kutuzov, the greatest of the Russian generals. Yet, Andrei has also abandoned his pregnant wife to seek glory in war. Leading up to Austerlitz he constantly fantasizes of having his “Toulon moment.” He idolizes Napoleon to the point of erasing his own identity. Andrei is the tragic man of St. Augustine’s insight, a man turned entirely inward to himself and can only think of himself and his desires at the exclusion of others.

During the Battle of Schöngrabern, Andrei experiences the encounter as a relatively detached observer. He heaps praise upon Captain Tushin’s isolated battery as the heroic unit that stymied the French advance and allowed the Russians under Prince Bagration to withdraw in good order and link up with Kutuzov before the disaster at Austerlitz. In his report he is like a giddy child, a reproductive image of the artillerists who were described as having a child-like joy at watching the town catch fire and blast grapeshot at the French soldiers advancing on their position. He is—like his hero, Napoleon—unable to see the human faces of war; the enemy are de-humanized or entirely invisible to him. He has lost his own humanity too, in the process.

Andrei embodies the discontented and alienated lives that many live. He is away from home and, therefore, away from his family. He does not seek the true masculine value of fatherhood; rather, he passes it off to his father and mother to look after his wife and soon-to-be-born child. He indulges in vanity and self-centered individualism that borders on a narcissism as he dreams of being the lone hero who will lead the Russians to a glorious victory against Napoleon—his hero—and win the laurels of all Russia. He is a man with his face centered on the muck and mud of the earth rather than the sky above which illuminates man and calls him to higher things.

War and Peace is a profoundly Christian novel. It is a story of the struggle to find joy and meaning in life. What is joy? How is it found? Andrei, like the rest of the characters at the beginning of the novel, are either unsure or seeking to find life’s fulfillment in things that cannot ultimately bring contentment to life. While the story develops and it becomes clear that love is the answer, especially the love found in marriage—family—the many characters are still unable to properly ascertain why marriage is that which will bring joy. Pierre, the other great hero, is the first to intuitively gather that love has something to do with it despite all his flaws and waffling agnosticism during his conflicted torment on whether to marry Hélène whom he acknowledges he doesn’t really love though proceeds to marry her which exhausts itself in disaster for all persons involved; though he later becomes a sort of missionary to others as the story develops.

The transformation of Andrei begins as he lay wounded at Austerlitz. Filled with an impetuous nihilistic streak when he grabs a fallen standard and charges the French knowing that he will die, his peering up at the sky after being wounded is one of the most majestic scenes in the novel. His wounding and solemn reflection upon the sky above leads to his, admittedly, slow transformation away from himself to others. “How quiet, peaceful, solemn, not at all as I ran…How was it I did not see that lofty sky before? And how happy I am to have found it at last! Yes! All is vanity, all falsehood, except the infinite sky.” Instead of forcibly changing the world—as was the dream of his hero Napoleon—Andrei finally accepts the world as it is and dwells in the marvelous beauty of it all for the first time.

Andrei’s first transformative moment is from the encounter with beauty amid chaos and individual wants. That he is looking up at the sky, the stars, is not something to overlook either. His slow march to embodying forgiveness and love of others begins with the clouds and fog of the battlefield giving way and his finding, for all intents and purposes, that true star which directs one to the incarnate God who preached love on earth and goodwill to men. Andrei’s conversion moment, his re-orientation, ought to remind one of the Annunciation to the Shepherds in the Gospel of St. Luke. It is not until Andrei has been brought low, humbled, that he glimpses eternity. Andrei’s slow journey to love of God, culminating in forgiveness and love of others (which is agape, or brotherly love), begins with his looking up to the heavens and finding a wonderous sight before his eyes. At long last he has the eyes to behold and receive. He is visited by divine as he lay wounded looking up at the sky in all its wonder and majesty rather than the clay to remold into a shallow parody of politicized and utilitarian life.

In fact, the Austerlitz transformation of Andrei continues when Pierre visits him for the first time in two years. While Andrei has become something of a reclusive contemplative monk who seeks to shun the world, Andrei is brought to life in this crypto-annunciation where Pierre serves as the angelic figure who snaps Andrei out of his contemplative slumber. As they journey in the carriage and discuss the great chain of being, Pierre ends his conversation by pointing to the sky—the sky that Andrei experienced in all its glory and majesty as he lay wounded. It is a slow journey with many trials, but Andrei’s transformation began as he crossed the threshold at the Battle of Austerlitz. In their conversation it becomes clear that Andrei, though confused and still disoriented in reorganizing his life, is on the path of service to others though he remains adamant he has forsaken that in service to himself.

The orientation of the eyes, which are also the windows to the soul, to the skies is an important inclusion that is not supposed to be missed. Imagination is that which is directed to the infinite, and the skies above are the window to the soul of God much like how human eyes are the windows to human souls. It is the encounter with beauty, all-consuming beauty, the infinite, which directs the human soul back to God. The sky calls us up; the earth drags us down.

From Austerlitz to Borodino, Andrei’s pilgrimage to God is completed as he lay beside Anatole Kugarin. Anatole, the man who carried on an affair with Natasha while married and destroyed Andrei’s and Natasha’s relationship, is moaning and whimpering like a child having lost his leg in battle. In that moment, feeling great pity for Anatole, Andrei utters unforgettable words, “Compassion, love of our brothers, for those who love us and for those who hate us, love of our enemies; yes, that love which God preached on earth.” A lesser man, a vengeful and spiteful man, could have found sadistic pleasure in the sufferings of such a man who has wounded one over the course of the years. Andrei takes the higher road. Dying, he asks for the gospels and, in meeting Natasha again who begs him to forgive her, Andrei’s self-giving love is consummated when he tells Natasha that he already has forgiven her. Andrei’s heroic journey is complete; from embodying the image of Achilles to becoming an image-bearer of Christ.

Part of Tolstoy’s realism is how one must go through chaotic struggle to find peace—love—in life. While not everyone will have to go through an Austerlitz and Borodino to reach that place, all need to reach the same place that Andrei arrives at by novel’s end. He is at peace with the world, himself, and others. This peace he finds is, as Tolstoy indicates by so many subtle and not-so subtle clues, through God. The removal of the centrality of God, however “invisible,” in readings of War and Peace cannot, therefore, come to understand the real heart of the work. Austerlitz and the other great battles are the battles that all struggle against sin; the reward of running that race is the bliss found in God which permits a true dwelling and appreciation of the world. Rather than conquering and remaking the world one finds peace in the world and is lifted up to the infinite expanse that is the heavens which transforms the soul to a love of the majesty (rather than blandness) of the world including love of others.

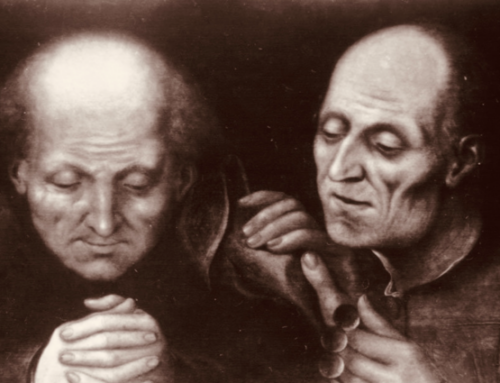

Advent, for Christians, signifies God’s love for humanity. It marks the first step of God’s desire to dwell with men—through the incarnation and birth of Christ. Amid chaos, internal and external struggles, one could look to the sky to see the light pointing to the ultimate beauty and majesty of God’s in-dwelling with man. The incarnation and birth of Christ is meant to be a beautiful and majestic moment—the time when God broke into the world of men for all to see. It should be the moment of humanity’s (re)awakening. It should be the moment of reorientation of our hearts to the love of others; the moment when one finds beauty, love, and peace in the world.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is a detail from “The Annunciation” (1501) by Bernardino Pinturicchio (1454-1513), courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Brilliant. Just a brilliant article.

Beautiful, the world can never be changed unless man changes. And this is one of those moments described and finds expression for others. A Testament to the wonders of life, of what we consider good and bad. In the end…God is Love!