Rather than being condemned as a manipulative populist feeding the people’s paranoia, Tucker Carlson should be commended for asking us to reconsider the first principles of conservatism, and for addressing the same ideas that G.K Chesterton also believed to be a threat to society: materialism, imperialism, feminism, and progressivism.

Responding to Mitt Romney’s op-ed in the Washington Post, Tucker Carlson delivered a now-famous monologue calling attention to the many problems burdening regular Americans.[1] He spoke out against the loss of manufacturing, morality, and manhood; all the while, people at the top of the social pyramid pay little attention to it or fail to recognize it as a problem. He lamented the breakdown of families caused by the spread of opioid addiction, militant feminism that vilifies men and denigrates domesticity, and disappearing opportunities for self-improvement and employment. He particularly criticized the conservative elite for not taking responsibility or caring, preferring to instead speak of GDP, tax cuts for privileged groups, and forever fighting wars in random backwaters. Should this continue, he concludes, then socialism will undoubtedly rear its ugly head in the U.S.

Responding to Mitt Romney’s op-ed in the Washington Post, Tucker Carlson delivered a now-famous monologue calling attention to the many problems burdening regular Americans.[1] He spoke out against the loss of manufacturing, morality, and manhood; all the while, people at the top of the social pyramid pay little attention to it or fail to recognize it as a problem. He lamented the breakdown of families caused by the spread of opioid addiction, militant feminism that vilifies men and denigrates domesticity, and disappearing opportunities for self-improvement and employment. He particularly criticized the conservative elite for not taking responsibility or caring, preferring to instead speak of GDP, tax cuts for privileged groups, and forever fighting wars in random backwaters. Should this continue, he concludes, then socialism will undoubtedly rear its ugly head in the U.S.

This has provoked a flurry of critical responses all over, particularly from the writers at National Review—many of whom deplore President Trump and populist conservatism. Those who disagreed with Mr. Carlson did so on the basis of where he places blame, mainly the elites in government and commerce. David French takes issue with the idea that individuals can’t advance when so many metrics of success show otherwise and, for that reason, sees the elites as “workers and strivers,” not “exploiters and elitists.” Both French and his colleague Jim Geraghty tout the charitable contributions of these workers and strivers as proof that they are not selfish—and, if so, their self-interest enriches them to the point of helping those in need.[2]

To follow up, Kevin Williamson and Kyle Smith find general fault in Mr. Carlson’s populism and shameless demagoguery—or “demagoguery’s near neighbor” as Mr. Smith puts it. If Mr. Carlson and so much of America have all these problems, what do they propose to do about it? And, where’s their evidence, besides feelings and personal anecdotes? In their view, the natural consequence of following Mr. Carlson’s logic is enlarging government and making it into some sort of parent who can arrange marriages, clean up drug addictions, and regulate away all the bad things in life. Williamson concludes the barrage of objections by finding the whole thing counterproductive and more a “status game,” a way to take the elite down a peg.[3]

On the other side, J. D. Vance agrees with Mr. Carlson and cites his own experience growing up in a drug-addled household as well as contrary evidence in the news to rebut the claim that the elites have little to do with the problems faced by Americans. On the contrary, they push addictive drugs onto unsuspecting patients with little care of the consequences to families, and they will happily empower the world’s largest police state to terrorize its people more efficiently. Mr. Vance maintains that though he doesn’t necessarily want the government to intervene, he wants those in government at least to give a little more thought on the matter and stop putting so much confidence in the marketplace.[4]

In addition to Vance’s heartfelt defense of Mr. Carlson’s complaint, William Krumholz and Kirk Jing at The Federalist takes a more logical approach with a point-for-point rebuttal of French and Ben Shapiro who also disagreed with Mr. Carlson. First, they show how they put the cart before the horse in arguing that marriage permits prosperity when it’s the other way around. Instability, caused by misguided welfare policies from the government and continual outsourcing of manufacturing jobs by business leaders, not automation, has kept down working-class men all over the country. Additionally, Mr. Krumholz calls attention to astronomical levels of debt at both in the private and public sphere, which again falls on the working class who are given few incentives to save yet plenty of incentives to spend beyond their means: “Cheap debt equals more debt.” Mr. Jing points out that the charity from elites is not only dwarfed by the much larger contributions of the working class that Carlson champions, but it mainly goes to causes that benefit the already wealthy.[5]

As this debate continues for conservatives, liberal commentators have largely ignored the whole matter, or have concluded once more that Mr. Carlson is a Neanderthal who caters to his fellow Trump-supporting troglodyte audience.

If nothing else, the debate that Mr. Carlson’s monologue has offered conservative readers very good articles over key issues that lie at the heart of American life. And yet, there is still more to say about it. Nearly all responses have delved into the logistical details of the monologue (which elites? which policies? which particular law or event caused this or could fix this?), but few, if any, have considered the monologue as a whole. In style and purpose, Mr. Carlson is approaching the wellbeing of America differently than the usual pundit—not as a shrill populist, but as a bona fide distributist. In this sense, he resembles less the “Mad as Hell” angry news anchor Howard Beale in Network that Kyle Smith suggests, but more so the famed early-twentieth century writer G.K. Chesterton, who upheld conservative values for the sake of the common man and common sense.

First, a primer on distributism (Joseph Pearce offers a good explanation here): In contrast to the theories of socialism and capitalism that held sway during his time—and which, ironically, still prevail today—Chesterton and his associates sought to promote an alternative to both of these theories, which, from their point of view were mainly two prongs on the same fork of progressivism. It was a system that would not aggrandize the state (as in socialism) or business (as in capitalism), but rather strive to keep all things small and human-scaled. This meant widespread decentralization and a healthy localism. This also meant that each family should own their own land and live as self-sufficiently as possible, leading to the unsuccessful Catholic Land Movement in England. Fond of the medieval villages, which exemplified distributism in key ways, distributists proposed that church should serve as the center of the community, not the factory or the courthouse.

To the dismay and confusion of progressive capitalists and socialists, distributism is not a system built upon maximizing productivity or material equality, but on maximizing the human person. Before examining policies, it considers the much deeper questions of what leads to human flourishing: faith, family, and community. Because of the many writings Chesterton devoted to these deeper questions, he has now become better known for his Christian apologetics (which would later influence the young atheist-turned-Christian C.S. Lewis) than his several essays and books dedicated to advocating distributism and criticizing modernism.

Because distributism dealt with underlying ideas, most arguments in its favor were deductive and humanistic, not empirical or scientific. This means that most distributists would purposely dispense with facts and figures (which form the substance of capitalist and socialist arguments) while still remaining intensely logical (separating it from populism or nationalism). Neither Chesterton nor Mr. Carlson would be so glib as to rally their audience to a popular cause; they instead see where their reasoning leads them, which sometimes frequently pits them against certain popular causes.

It seems more likely that Mr. Carlson provoked a response less because of what he said, but more because of how he said it. Because he focused on the person in general, and not specific facts and data, his monologue resonated far better with normal audiences than the whole mass of analyses produced by think-tank writers. Intellectually, he played dirty by going “populist,” and Mr. Williamson was honest enough to show his disgust: “I cannot imagine how a man of Tucker Carlson’s wit and intelligence participates in such risible pageantry without being embarrassed to death.”

Instead of taking it this way (and betraying a slight hint of pettiness), it would be better to interpret Mr. Carlson’s monologue as an invitation to reconsider the first principles of conservatism. In fact, much of the structure and content of his argument is suspiciously close to Chesterton’s book, What’s Wrong with the World, in which Chesterton suggests that people first develop their vision of a healthy society before they set off on fixing the supposed ills that plague it.

When this is done, it becomes apparent that a healthy society is one where every man and woman can live a fulfilling life. This involves providing material goods like owning property, working at a good job, and upholding law and order as well as supporting spiritual goods like marriage, family, friendship, and a healthy sense of belonging. What threatens these goods is not necessarily specific groups or individuals, but ideas. Despite being a century apart, both Mr. Carlson and Chesterton address the same ideas that threaten society: materialism, imperialism, feminism, and progressivism.

Put briefly—since Chesterton and Mr. Carlson have already articulated these things superbly—these ideas have corrupted institutions, which in turn have corrupted the people, explaining the widespread modern malaise. Materialism has corrupted government and businesses by making them large, oppressive, and focused on efficiency and authority more than human welfare. Imperialism has corrupted the idea of home and community, reducing close relationships, tradition, and history to a mere system of values and legal mechanisms that can transfer anywhere and everywhere. Feminism has corrupted the family by destroying the natural and complementary roles of men and women in the interest of making both unimaginative wage slaves competing with one another at the cost of their children. And progressivism has corrupted schools and universities by making them outlets of propaganda and bosh instead of sources of culture and intellectual development.

True, many have identified these problems and have proposed solutions, but as a whole these efforts will go unnoticed until both elites and non-elites tackle them together. Policy wonks can publish paper after paper, each crammed with technical, self-important jargon, but the subjects they explain should be addressed to the people, not elites or other wonks. People in power should shun the temptation to seclude themselves in a bubble with their peers and grow out of touch with normal people—a problem Andrew Carnegie speaks of at length in The Gospel of Wealth. Everyone else should strive for self-reliance and resist the socialist impulse to shove their problems onto some leviathan government; Mr. Carlson’s detractors are right to fear this, though they are wrong to think that Mr. Carlson does not fear this as well when he concludes with this very point.

Rather than being condemned as a manipulative populist feeding the people’s paranoia, Mr. Carlson should be commended for voicing these concerns and putting them on the forefront and reviving optimism and humanity of distributism. Both conservatives and liberal thinkers should take it as a challenge to come up with solutions, not excuses and sophistry—which is what critics largely respond with, albeit with zest and insight. All Americans should have an interest in recovering the things that help human beings flourish, and not allow details to obscure the big picture.

This essay was first published here in January 2019.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Notes:

[1] See Mitt Romney’s op-ed here; see Tucker Carlson’s monologue here.

[2] “The Right Should Reject Tucker Carlson’s Victimhood Populism,” by David French, National Review (January 4, 2019); “Tucker Carlson’s Populist Cri de Cœur,” by Jim Geraghty, National Review (January 4, 2019).

[3] “The Non-Debate,” by Kevin D. Williamson, National Review (January 8, 2019); Government Can’t Heal Us, Tucker Carlson,” by Kyle Smith, National Review (January 5, 2019).

[4] “The Health of Nations,” by D.D. Vance, National Review (January 7, 2019).

[5] “Tucker Carlson Is Right About America’s Elites And Working Class,” by Willis L. Krumholz, The Federalist (January 8, 2019); “It’s Not ‘Victimhood Populism’ To Point Out Our Elites Have Failed,” by Kirk Jing, The Federalist (January 9, 2019); “Tucker Carlson Claims Market Capitalism Has Undermined American Society. He’s Wrong,” by Ben Shapiro, The Daily Wire (January 4, 2019).

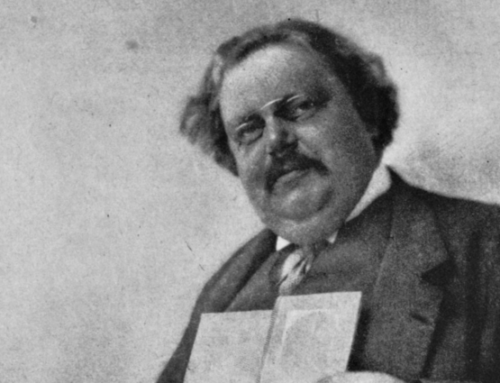

The featured image, uploaded by Gage Skidmore, is a photograph of Tucker Carlson. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Very educational. This opens another door forward.

OTOH, the people’s paranoia….its not paranoia when they really are out to get ya’.

Speaking of distributionism, while Benjamin Franklin might nothave advocated it, he once said, “[W]hat we have above what we can use is not properly ours tho’ we possess it.,” and a provision in the 1776 Pennsylvania constitution, approved by Franklin but later removed, read, “That an enormous Proportion of Property vested in a few individuals is dangerous to the Rights and destructive to the Common Happiness of Mankind and therefore every free state has the Right by its laws to discourage the Possession of such Property.”

Thank you for an extremely informative–and helpful–way of understanding this prominent conservative voice. The parallels you draw are both astute and persuasive.

Very sensible and fair. Tucker Carlson’s observations were on target.

That’s why they got rid of him. Surprised?

Don’t be.

I will look for Chesterton’s book “What’s Wrong with the World?”

Re “Mr. Vance maintains that though he doesn’t necessarily want the government to intervene, he wants those in government at least to give a little more thought on the matter and stop putting so much confidence in the marketplace.[4]”

MORE than additional intervention, we call on the “government” to do its job by prosecuting criminals to the full extent of laws already on our books . And this includes prosecution/punishment of corporate/media/pharma/deep state/international CRIMINALS.

If Tucker Carlson was truly a conservative thinker, he would understand dangerous game he played in alluding to the fact that the insurrection on January 6th was just an inside job. Patriot Purge was not grounded in fact. But hey, just because one side is overthrowing the Constitution and culturally imposing its will it must be okay for us on the right to do it too, right? Wrong. Tucker Carlson has been nothing but an opportunist and a threat to the American Republic, much like the leftist movement he pretends to deplore. He and the NatCons believe in overstepping the bounds of the Constitution, much like the left he deplores. A return to first principles and limited government would be nice, but you won’t find it with Tucker and his essentially left-leaning, opportunistic “thought”.

The comparison is mistaken and defies the Catholic views regarding Virtue and Morality. He represented a liability to the organization he used to work for due to the nature of his journalism and the hypocrisy of his positions. More recently, he was found to be prone to statements considered (by any civilized society) as blatantly racist. Are these qualifications in any way consistent with Chesterton positions and ideas? A true Catholic man doesn’t dwell on innuendo and scandal: a leveled head and a cheerful disposition were the marks of the man Chesterton was. Besides, a powerful intellect’s not necessarily a requirement for a Catholic man but any Catholic man who aspires to be compared to Chesterton would certainly had t express complex ideas and concepts clearly and consistently while Mr. Carson is better known by his rhetoric and his smarts, not his intelligence or intellectual capacity.

I’m glad you say Chesterton, “espoused conservative values” and not “a conservative”. Chesterton was smart enough to be frustrated with both sides, seeing that neither truly was living up to the call of Christ through the Church. Which is why Chesterton was happy to say this about Conservatives and progressives:

“The whole modern world has divided itself into Conservatives and Progressives. The business of Progressives is to go on making mistakes. The business of Conservatives is to prevent mistakes from being corrected. Even when the revolutionist might himself repent of his revolution, the traditionalist is already defending it as part of his tradition. Thus we have two great types — the advanced person who rushes us into ruin, and the retrospective person who admires the ruins. He admires them especially by moonlight, not to say moonshine. Each new blunder of the progressive or prig becomes instantly a legend of immemorial antiquity for the snob. This is called the balance, or mutual check, in our Constitution.”

Personally, I think it’s an insult to the memory of G. K. Chesterton to compare him to Tucker Carlson.