It’s always important to remember that the Founders of our country did not predicate their arguments for independence on some idea of liberty as the release from all constraints of law or qualms of conscience, but on real, reasoned understandings of the duties that come with freedom and the gratitude that binds us to the past and to each other.

On Tuesday afternoon, three camp chairs facing out onto the street showed up beside one of the light posts on Main Street in Lander. By tonight, more and more of them will crowd almost every available curbside space from one end of town to the other. Those who leave them, confident that they will not be moved or stolen, are laying claim to their spots for the spectacle that will unfold tomorrow. The Fourth of July parade in Lander harkens back to the deep traditions of our country, and it’s an unabashed celebration. At the end of it, after every group in the region, after Native-American dancers and marching bands and victorious swim teams have their moment of recognition, the fire engines will gather on both sides of one block. Children and teenagers—our PEAK students among them—will start running toward that block from both ends of town. Great geysers of water will shoot up into the air from the hoses, and getting drenched will be a kind of complement and prologue to the extraordinary town-wide fireworks displays of the night to come.

On Tuesday afternoon, three camp chairs facing out onto the street showed up beside one of the light posts on Main Street in Lander. By tonight, more and more of them will crowd almost every available curbside space from one end of town to the other. Those who leave them, confident that they will not be moved or stolen, are laying claim to their spots for the spectacle that will unfold tomorrow. The Fourth of July parade in Lander harkens back to the deep traditions of our country, and it’s an unabashed celebration. At the end of it, after every group in the region, after Native-American dancers and marching bands and victorious swim teams have their moment of recognition, the fire engines will gather on both sides of one block. Children and teenagers—our PEAK students among them—will start running toward that block from both ends of town. Great geysers of water will shoot up into the air from the hoses, and getting drenched will be a kind of complement and prologue to the extraordinary town-wide fireworks displays of the night to come.

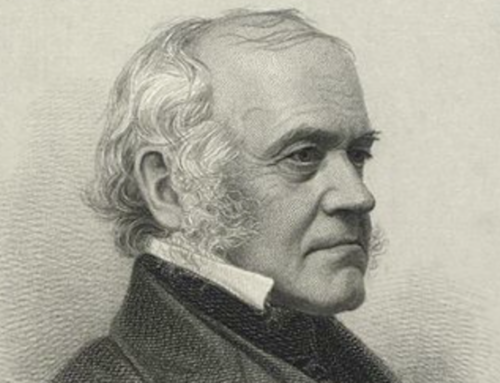

What are we celebrating? If we look at the rancor of public discourse these days, it’s easy to forget. That’s why I’m so heartened by a book I neglected to put on my summer reading list a few weeks back. Wilfred M. McClay’s Land of Hope, a new history of the United States, sets out to remind us of what should make us so grateful on occasions like these. Prof. McClay, who teaches at the University of Tulsa, spoke here at Wyoming Catholic College back in April, and his insights on the “forgotten virtue of loyalty” were moving. At the time, his book had not yet been released, but from what he said about it, we already knew that loyalty to our country would be a crucial dimension. And in fact, it radiates from the very first pages of this book. I hope that it rapidly displaces the cynical textbooks foisted upon American students for several generations.

Look at this simple reminder with which he starts: “You didn’t call yourself into existence out of the void. You didn’t invent the language you speak, or the food you eat, or the songs you sing. You didn’t build the home you grew up in, or pave the streets you walked, or devise the subjects you learned in school. Others were responsible for these things. Others, especially your parents, taught you to walk, to talk, to read, to dress, to behave properly, and everything else that goes with everyday life in a civilized society, things that you mainly take for granted.”

As simple as these things seem, Prof. McClay is addressing what has come to be a major problem in the America we now inhabit—the sense that individuals do in some sense get to call themselves into existence out of the void, as though they were somehow not only self-inventing, but also deprived of choices about who to be from the outset (a contradiction that C.S. Lewis’s Screwtape must surely relish). Prof. McClay’s insistence that we owe so many crucial things to others cannot help but remind his readers that human beings are by nature social and political creatures, not robbed from the outset, but given the very basis of self-understanding.

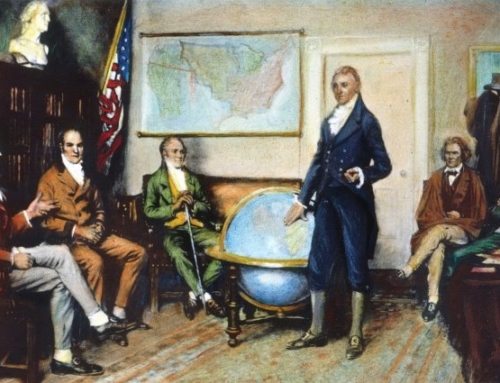

The keynote of Prof. McClay’s book comes very early in the first chapter, “Beginnings,” in which he looks back to the first people from Asia who crossed onto this continent as well as to Leif Eriksson and other Norse explorers. Prof. McClay sees a continuity that characterizes what this nation has, in some sense, always been:

Maybe the lost civilizations of the first Americans and the episodic voyages of Erickson and other Norsemen, taken together, do point powerfully, if indirectly, to the recognizable beginnings of American history. For they point to the presence of America in the world’s imagination as an idea, as a land of hope, of refuge and opportunity, of a second chance at life for those willing to take it.

That hope has never been groundless. Just looking west from where we live outside Lander, as in the photograph above, you can feel it in the land itself, the promise of beauty and difficulty and independence. It’s always important to remember that the Founders of our country did not predicate their arguments for independence on some idea of liberty as the release from all constraints of law or qualms of conscience, but on real, reasoned understandings of the duties that come with freedom and the gratitude that binds us to the past and to each other.

Prof. McClay’s book is itself a sign of hope, and I look forward to finishing it this summer. Speaking of hope, I will be taking these next two weeks to celebrate the wedding of my youngest daughter. Please keep her and the whole community of Wyoming Catholic College in your prayers. And Happy Fourth of July!

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics as we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is “Aurora Borealis” (1865) by Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900) and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Leave A Comment