Propaganda has both short-term and long-term consequences. In the short term, propaganda can influence people to support particular policies, even if those policies cut against their best interests. In the long run, propaganda erodes democratic foundations.

The Imaginative Conservative‘s Brad Birzer interviews Abigail R. Hall, co-author of “Manufacturing Militarism,” which Dr. Birzer reviewed in these pages.

TIC: Abby, thank you so much for taking your valuable time to talk with us. As you know, I’ve been a fan of your work for a long time, but I think you’ve taken your scholarship to a whole new level with Manufacturing Militarism. It is at once brilliant and disturbing. Before we get into the book though, can you give us a bit of background about yourself?

Hall: I am an Associate Professor of Economics at Bellarmine University in Louisville, Kentucky. I am an affiliated scholar with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and an affiliated scholar with the Foundation for Economic Education. I am a Senior Fellow at the Pegasus Institute and a Research Fellow at the Independent Institute. I have a PhD in economics from George Mason University.

TIC: Excellent. And, can you tell us a little bit about your collaborations with Chris Coyne?

Hall: Chris and I have been working together for nearly a decade on topics related broadly to defense and national security. We’ve written on policing and policing militarization, imperialism, human rights abuses, whistleblowers, cronyism, military technology, and the intersection of counterterrorism and drug policy. In 2018, we coauthored our first book together, Tyranny Comes Home: The Domestic Fate of U.S. Militarism. In that book, we develop a framework for understanding how the tools of social control developed for foreign intervention abroad come to be used domestically. We apply it to the post-9/11 context.

The research program we work in is one I am very passionate about—and I know Chris is as well. When discussing foreign intervention—whether war, humanitarian aid, etc.—there is this real tendency for people to ignore two things. First, people tend to ignore the non-monetary costs of these activities. We might talk about the loss of military personnel or civilians in war as a nonpecuniary cost, but even this fails to capture all that is lost when we engage in intervention. Our work helps to shed light on these overlooked costs. For example, we’ve written on how troop deployments to Iraq in 2003 worsened the reaction times of first responders domestically. In Tyranny, we illustrated how intervention has profound domestic costs with respect to civil liberties. Second, even those who are generally quite skeptical of government have this patently bizarre tendency to confer positively magical powers on state actors when they operate in the space of foreign intervention. It’s as though the lessons of economics go out the window. We push back against this way of thinking and show that the problems of government aren’t lessened in an international geopolitical space but exacerbated.

TIC: Definitely important insights. Let’s go to basics and first principles. What inspired you to write MM?

Hall: This idea is one we’ve been working on for several years—and started on shortly after we finished Tyranny. One of the things that became clear to us as we were writing that book was that there is a clear role of propaganda in the war on terror. We wanted to explore that role, but also understand the form that propaganda took in the post-9/11 period. We wanted to know how propaganda was used, how was it similar to propaganda used in previous conflicts, and how was it dissimilar.

TIC: What thing surprised you most in your research and writing?

Hall: I was surprised at the historical context of all the cases we discuss. From sports propaganda to propaganda in film, to the war in Iraq, the roots run deep. These historical dynamics that are necessary to understand in order to have the appropriate perspective on contemporary activities. We did a lot of historical reading. In some cases, the histories are remarkably complex. In order to understand the propaganda surrounding the invasion of Iraq in 2003, for instance, you have to understand the geopolitical history of the Middle East, but particularly the interactions between Iraq and the United States. I was especially surprised by how many times “characters” from an earlier chapter of history came back in a critical capacity later on.

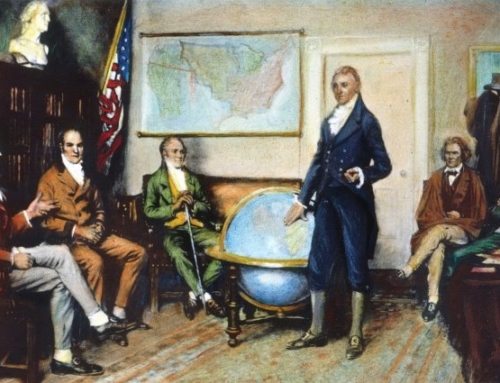

TIC: Your book is premised on the idea that America is a liberal democratic state, and you posit (rightly, to be sure) that propaganda undermines the very foundations of such a regime. When is (or was) the point of no return? It strikes me, at least from reading your book, that we’ve not been a liberal democracy since 1917.

Hall: I don’t know that there is some critical tipping point, and I am not sure where we are on Hayek’s “road to serfdom.” We do argue that propaganda has both short-term and long-term consequences. In the short term, propaganda can influence people to support particular policies, even if those policies cut against their best interests. In the long run, as you rightly point out, propaganda erodes democratic foundations. Namely, propaganda inhibits some of the critical checks and balances on government by limiting and changing the information people use to make rational decisions. You can’t hold people accountable if you don’t have the information necessary to do so or the means to reward or punish behavior.

TIC: So, I’m not a sports guy (except for the Royals in baseball), but I was really struck by how the NHL and the NFL have worked hand in hand with the military. Can you explain a bit more about “paid patriotism”? And, why do you think the public is so accepting of this?

Hall: Paid patriotism refers to the practice whereby the DOD paid major sports franchises to engage in a variety of “patriotic displays.” Think about surprise homecomings for military personnel, fly-overs, full field flag display, a military feature during home games, and so on. In many cases in the post-9/11 period, these weren’t genuine displays of patriotism, but paid propaganda. This is an example of propaganda as a means of fostering a broader culture of militarism.

I think there are a few things going on in terms of “public acceptance.” For one, I don’t think a lot of people actually know about this. It caused a minor scandal when the late Senator McCain’s office broke the story about a decade ago. They released a report that showed major sports teams received millions over a period of several years. But the report wasn’t comprehensive—we’re missing years of data on how much money the DOD spent. When I’ve mentioned this to people, I’d say only 30-40% have heard about it at all.

For those that have heard of it, there is this tendency to direct their anger toward organizations like the NFL as opposed to the government. There is this sentiment that it’s wrong of an NFL franchise to take money for patriotic displays—but not wrong of the DOD to offer it. I don’t know that I have a good idea of why that is the case. Perhaps it goes to show how deeply ingrained these patriotic ideas are in American society and how powerful patriotic appeals can be as a rhetorical tool. The sports chapter was eye-opening for me. There is quite a bit of literature on sport as a substitute for war and the language of war being transposed onto sports and vice versa. It was challenging but satisfying to weave those threads together.

TIC: Let’s talk about the TSA for a bit. Security Theater. This part of your book just made me so angry. Being 53, I remember very well how fun flying was before 9/11. What would need to be done to ask—effectively and determinatively—whether the TSA has saved lives or not? That is, how do we measure its efficacy?

Hall: The research for this chapter made me angry too. If you don’t like the TSA, reading this chapter will not help to sway to your opinion in their favor.

There are a couple of different questions here. The first question is one of efficacy and the other is the cost of the intervention relative to that efficacy. In some cases, we don’t have a lot of data to talk about the true value of some TSA programs. For a lot of TSA programs, the information about program performance is deliberately withheld citing concerns of “national security.” In other cases, they don’t collect the data at all. This is obviously problematic because it prevents us from answering the very simple question of, “is this doing anything?”

The data that we do have doesn’t paint a very pretty picture. We know that when it comes to apprehending bombmaking or other hazardous materials the TSA fails its own tests with alarming regularity—think well and above a 75% failure rate.

This leads us to the cost of an intervention. Even if an intervention is effective, is it worth the price? Throughout the TSA chapter, we draw on the work of John Mueller and Mark Stewart—who have written extensively about both threat inflation and the cost of counterterrorism policies. In one of their papers, they analyze the effectiveness of the Federal Air Marshal Service (FAMS). They find that the FAMS spends $180 million to save one life, whereas the government sets the regulatory price at $1-$10 million per life saved. In other words, FAMS miserably fails to meet the government standards for “cost per life saved.”

TIC: And, this leads me to some practical questions. You and Coyne offer a brilliant critique of the last 100+ years of government (and quasi government or government inspired and sponsored) propaganda. What are some practical things that could be done to put the United States back on a solid constitutional foundation? Is there anyone in government—Rand Paul or Thomas Massie, for example—fighting for the right side in all of this?

Hall: In the conclusion, we discuss a few possible options for countering propaganda and this march toward militarism. We talk about government regulations as one possible method—though we are not at all optimistic that this would be a successful route. This would essentially require members of government to constrain their own behavior. We have a large literature from constitutional political economy—and a lot of history—that tells us why this is unlikely to happen. We also discuss the importance of other groups of people, the media, whistleblowers, and so on as potential solutions. I don’t think there is a silver bullet or monocausal fix.

In terms of practical steps, I think one thing that people can do is critically question the information that they receive from government. This doesn’t mean you have to assume that government is lying to you at every turn, but it does mean that people can recognize that we aren’t in an idealized setting where officials offer completely truthful, unbiased information. People ought not to accept information blindly. People need to examine the militaristic attitudes that have become so incredibly pervasive. We talk about the concept of “citizen inoculation” to propaganda. This is an important step in that process.

TIC: Amen. Abby, it’s been a real pleasure talking with you. Thank you so much for your time and your powerful insights. Before we end, can you give us some info as to your next project?

Hall: I have a few things working at the moment. Chris Coyne and I, along with our coauthor Anne Bradley, are working on a monograph on the political economy of terrorism applying insights from Austrian economics and public choice. Chris and I are thinking through our next book projects—we have a couple ideas we’re pondering. We plan to tackle the military-industrial complex in a more comprehensive way. Outside of these projects, I’m working on a coauthored piece understanding the effects of U.S. border wall construction on migrant deaths. The border wall and the actions of CBP, if we remember, are all tied to counterterrorism policy, and so, we have another unintended consequence. So lots of work to do!

TIC: Wonderful. Thank you again, Abby.

Hall: My pleasure!

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Leave A Comment