People in my hometown of Galveston, Texas don’t have a superb explanation or philosophy for their city. It’s just their home. It’s a beautiful place with a beautiful history. Statues still stand. The streets are largely clean; the police take care to contain crime to the smallest radius possible. That all is a clear contrast with the capital city of Washington, where I came to work.

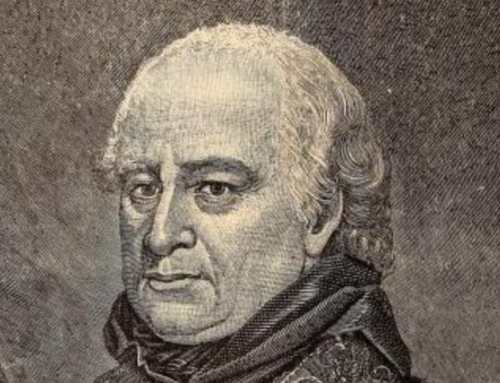

When I first moved to Washington, D.C., I sought out a statue of the Spanish Revolutionary War general Bernardo de Galvez. He’s the namesake of my hometown: Galveston, Texas. I found it directly in front of the State Department, wholly engulfed by a homeless encampment. Drugs, trash, and strung-out users lay all over the lawn. I had come to send a picture of the general to my family, to show them our representation in the nation’s capital. I left without taking a photo at all.

When I first moved to Washington, D.C., I sought out a statue of the Spanish Revolutionary War general Bernardo de Galvez. He’s the namesake of my hometown: Galveston, Texas. I found it directly in front of the State Department, wholly engulfed by a homeless encampment. Drugs, trash, and strung-out users lay all over the lawn. I had come to send a picture of the general to my family, to show them our representation in the nation’s capital. I left without taking a photo at all.

Galveston is a city constantly reminded of its mortality. In my short lifetime, it’s been hit by four major hurricanes and countless tropical storms. It’s the site of the deadliest natural disaster in American history: the 1900 Storm. Local businesses paint flood-level markers on their walls with the dates and names of major storms. Many of the markers stand several feet above my head.

It has always been remarkable to me that a long-irrelevant cotton port constantly subjected to natural destruction has maintained such care for itself. Galveston is home to the oldest churches in Texas and many of the most beautiful. The Bishop’s Palace dominates its main thoroughfare, accompanied by the Moody Mansion and countless Victorian marvels that once belonged to cotton merchants and shipping tycoons. Even the average home in the city is a small Victorian, likely restored two or three times over after enduring a century of storms.

People in Galveston don’t have a superb explanation or philosophy for their city. It’s just their home. It’s a beautiful place with a beautiful history. Statues still stand. The streets are largely clean; the police take care to contain crime to the smallest radius possible. They just want their kids to enjoy living there. They want their kids to know who came before them. They’re not going to let vandals take that away from them.

That all is a clear contrast with Washington. Vandals are not only tolerated, but occupy the highest public offices. Washington is the most powerful city on earth and the wealthiest in America. Cleaning the city up would be easy, and it would pay dividends for America’s image around the world and help burnish perceptions of the political class. But instead, brutalist atrocities cruelly named after L’Enfant accompany homelessness, crime, trash, and drugs. Crumbling infrastructure and public parks unsafe for children sit just blocks from the Capitol and the White House. There’s no public policy benefit to this. There are no white papers that advocate filth. They can’t even blame hurricanes.

The capital is a town filled with vandals—nihilists who hate their history, themselves, and the children they don’t and won’t have. Some live in cramped apartments, others in Kalorama mansions, and a few in the White House. They pretend to be an enlightened ruling class, but they can’t even pick up the trash on their own streets.

The people in Galveston are ship crewmen, restaurant workers, fishermen, and roughnecks. Some are artists, surfers, and nurses. Most don’t have master’s degrees, fewer still have read Aristotle. But they maintain their community of souls, and they love their homes. It’s time for Washington, D.C., to dust off the statue of General Galvez and learn from the people it once represented.

Republished with gracious permission from The American Conservative (August 2021).

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image, uploaded by Farragutful, is a photograph of the statue of Bernardo de Gálvez along Virginia Avenue, N.W., in Washington, D.C. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Washington is run by which political party? Great article!

Ah, life among brutality atrocities, life in America today…..

This is such an awesome read! And so very true. Very well said. Thank you!

When I was very young I used to spend a long vacation in Washington with cousins. I could ride my bike from Foxhall Road down to the Pentagon, by myself and safely. It was a beautiful city, loved and cared for by residents and tourists alike.