Perhaps the final fall that proceeds from a life of prideful “success,” irrespective of the judgment of God which follows, is the miserable way in which tyrants die.

I was intrigued by some of the comments prompted by my essay “Does History Repeat Itself?” In particular, my eyebrows were raised by the objections to my claim “that history shows prideful choices preceding a fall.” It was pointed out by one of my most lucid interlocutors that this is not always the case: “You say [that] ‘history shows prideful choices preceding a fall’, well, sometimes prideful choices do not precede a fall. You pick Napoleon as your example. Alexander the Great was pretty prideful, and he did not have a fall. Generals Sherman and Patton were pretty prideful, and they didn’t have falls. And on the converse, General Robert E. Lee was fairly humble, and he didn’t win. No, you’re being selective in your data. Yes, sin has great consequences, and yet there are sinners that rise to great heights. Henry VIII, a despicable man in my opinion, never got the fall he deserved….”

I was intrigued by some of the comments prompted by my essay “Does History Repeat Itself?” In particular, my eyebrows were raised by the objections to my claim “that history shows prideful choices preceding a fall.” It was pointed out by one of my most lucid interlocutors that this is not always the case: “You say [that] ‘history shows prideful choices preceding a fall’, well, sometimes prideful choices do not precede a fall. You pick Napoleon as your example. Alexander the Great was pretty prideful, and he did not have a fall. Generals Sherman and Patton were pretty prideful, and they didn’t have falls. And on the converse, General Robert E. Lee was fairly humble, and he didn’t win. No, you’re being selective in your data. Yes, sin has great consequences, and yet there are sinners that rise to great heights. Henry VIII, a despicable man in my opinion, never got the fall he deserved….”

These are very intelligent, thoughtful and thought-provoking observations, which require a thoughtful and thought-provoking response.

The first response I would make is that I did not actually offer Napoleon as an example of pride preceding a fall. I mentioned him to make a comparison between his march on Moscow in 1812 and Hitler’s in 1941, doing so to illustrate that human motive was the substance of history whereas technology was accidental, philosophically speaking.

This clarification having been made, let’s address my interlocutor’s principal objection. He says that “sometimes prideful choices do not precede a fall,” offering the examples of prideful men, such as Alexander the Great, Henry VIII and Generals Sherman and Patten, who enjoyed great military or political success, as compared to the “fairly humble” Robert E. Lee, who suffered humiliating military and political defeat. Who could argue with such a line of reasoning? Indeed, we could add other prideful “success stories,” such as Josef Stalin or Chairman Mao, both of whom lived to ripe old age having prevented millions of their fellow countrymen from doing likewise through the millions of deaths for which they were responsible. These men literally got away with bloody murder, becoming the most successful serial killers in history in terms of both the numbers of their victims and the fact that they were never brought to trial. Did pride precede a fall in their cases?

Leaving aside the judgment of God, which within the context of our strictly historical discussion might be considered a deus ex machina, it does seem that worldly people enjoy great worldly success. It is usually the wicked who lord it over their fellow men, which is why, in the words of the Salve Regina, this world is a “vale of tears” and a “land of exile.” It is also why J. R. R. Tolkien considered history to be the “long defeat” which only offers “occasional glimpses of final victory.”

This whole issue was addressed by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who knew more than most about the evil consequences of the decisions made in ivory towers by those who had made a success of pride. Struggling with the mystery of suffering, having suffered more than most, Solzhenitsyn wondered why the innocent victims of evil seemed to suffer more than the perpetrators of evil. If suffering was a consequence of sin, did that mean that he and the millions of other prisoners in Stalin’s camps were more evil than those who had escaped their miserable fate, including the very people who had sent them to prison? Did it mean that the torturer was less evil than the tortured? And what of those proud souls who had prospered rather than suffered? What of Stalin himself? “Why does fate not punish them?” Solzhenitsyn asked. “Why do they prosper?” He then answered his own questions:

[T]he only solution to this would be that the meaning of earthly existence lies not, as we have grown used to thinking, in prospering, but … in the development of the soul. From that point of view our torturers have been punished most horribly of all: they are turning into swine, they are departing downward from humanity.

In these few words, Solzhenitsyn has encapsulated what I was trying to say in my previous essay with respective to the destructive consequences of pride. Apart from the numerous innocent victims of pride, it is the proud themselves who ultimately suffer the consequences of their choices. Insofar as they remain proud, they are becoming less human. They are falling from humanity.

We can only see Alexander the Great, Napoleon, Hitler and Stalin as representing prideful “success” if we buy into the lie that worldly “empowerment” is synonymous with success and that such power is the purpose of life and therefore of history.

As a postscript, it might be worth mentioning that Alexander the Great was forced to abandon his military adventures to avoid the rebellion of his troops, his pride being humbled, and that his posthumous legacy was a series of civil wars which ripped his short-lived empire apart. The respective marches on Moscow by Napoleon and Hitler have become a byword for the disastrous consequences of political and militaristic pride. As for how “successful” other tyrants, such as Henry VIII, Stalin or Mao, might have felt in their final days, it is doubtful that any of them was at peace with themselves or with God. Perhaps the final fall that proceeds from a life of prideful “success,” irrespective of the judgment of God which follows, is the miserable way in which such tyrants die. Perhaps, as a means of illustrating this, I will devote a future essay to the final pathetically miserable days of another “successful” tyrant, Elizabeth I.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

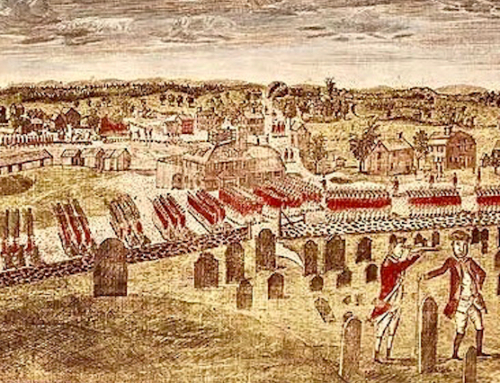

The featured image is “Napoleon in burning Moscow” (1841) by Adam Albrecht, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. It has been brightened for clarity.

Thanks Joseph for your gracious reply. It does seem the Psalmist himself, per Ps 10:1-28, struggled with the apparent “success” of the wicked. But then the eternal post-history perspective both Solzhenitsyn offer is a wonderful albeit ‘expanded’ corrective. We Christian are notorious for too quickly seeing reality as do the secular modernist/post-modernist. Thanks again for your provocative mind and writings.

As with most things, we can look to Solzhenitsyn for some pretty good answers. (Which he learned the very hard way.)

I did not read your original essay as speaking about individual pride, but of societal pride.

One only needs to read of Stalin’s well-deserved suffering in his last hours/days to understand that it was mostly the makings of his own decisions and actions. His last dying breath had him shaking his fist in anger, seemingly at God, by those few who were present. If ever there were a textbook case of hell being “a state of getting everything one wants”, ol’ Joe would be the photo child example.

History and pride, what a great title that pretty much sums up the zeitgeist of one’s life. The forces of history forming the spirit of the time that has been laid in place to welcome our birth. I am currently reading a book that traces the uncomfortable and fearful subject of the hardening of one’s heart through the history of an individual’s, or a nation’s, fall that is documented in the Bible. Pride is an internal attitude often presented in fear, hatred, anxiety, jealousy, envy, lust, boasting , just to name a few terrible powers that often can’t be tamed. It is that dread , that lack , or loss, of not remembering what God has said and how we are accountable to Him.