It is true that we can’t say with certainty what will happen in the future because it will depend on the choices we make. But we can be almost certain what will happen in the future based upon what we know about the past.

It’s not often that I find myself disagreeing with G. K. Chesterton. This is just as well. One who often finds himself disagreeing with G. K. Chesterton will, more often than not, find himself proven wrong. And yet one who sometimes disagrees with him might sometimes be right. In the immortal words of Pliny the Elder, Nemo mortalium omnibus horis sapit. No mere mortal is at all hours wise. Even Chesterton sometimes gets things wrong!

It’s not often that I find myself disagreeing with G. K. Chesterton. This is just as well. One who often finds himself disagreeing with G. K. Chesterton will, more often than not, find himself proven wrong. And yet one who sometimes disagrees with him might sometimes be right. In the immortal words of Pliny the Elder, Nemo mortalium omnibus horis sapit. No mere mortal is at all hours wise. Even Chesterton sometimes gets things wrong!

The assertion by Chesterton which has caused me to raise my eyebrows and, more to the point, raise an objection is his claim that history doesn’t repeat itself.

In his essay, “A Much Repeated Repetition,” published in the Daily News in 1904, Chesterton suggested that the person who first said that history repeats itself “must have been a man with a very dim and strange mind.” Although he conceded “a grain of veracity” in the phrase, he argued that “the correct way of stating the matter would be, ‘The Universe repeats itself, with the possible exception of history’.” He continues:

Of all earthly studies history is the only one that doesn’t repeat itself. This is the very definition of the divinity of man. Astronomy repeats itself; botany repeats itself: trigonometry repeats itself; mechanics repeats itself; compound long division repeats itself. Every sum if worked out in the same way at any time will bring out the same answer. But it is the peculiarity and fascination of the sums of history that with the most perfect calculation the sum comes out with a slight mysterious difference every time.

The point that Chesterton is making is that man has free will, the mark of what he calls “the divinity of man.” This means that men throughout history have the freedom to act in one way or the other. Their choices are not predetermined and, therefore, history is not a determinist science. This sems sensible enough but the problem is that men are not free to act in one way or the other after the event. It is simply not true to say that men throughout history “have freedom.” They do not have it; they had it. Once a decision has been made and acted upon, it has happened and has consequences. Having chosen to act in one way, we can’t turn back time and act in the other way instead. The past is an objective reality. It has happened in one particular way and can no longer happen in any other way. It is set in stone, which is why we learn objective lessons by the studying of it.

It is true that we can’t say with certainty what will happen in the future because it will depend on the choices we make. But we can be almost certain what will happen in the future based upon what we know about the past. We can know this because history does repeat itself. It is true, for instance, that history shows prideful choices preceding a fall. If this is true throughout history, we can be relatively certain that it will continue to be true in the future. It is equally true that, throughout history, selfishness, or what theologians call sin, has destructive consequences, whereas selflessness, what theologians call virtue, has positive consequences. The seven deadly sins are as deadly today and tomorrow as they were yesterday. The seven virtues – faith, hope, charity, prudence, justice, temperance and fortitude – are as life-giving and life-affirming today and tomorrow as they were yesterday. These are moral laws governing the life of man in society which are as objectively real as are the laws of physics or mathematics.

Philosophically speaking, we can say that sin and virtue are the very substance of history, the perennial and essential “stuff” of which it is made, whereas the technological trappings of every age, which do indeed change, are merely accidental. Take, for instance, Napoleon’s march on Moscow in 1812 and the German march on Moscow in 1941. The weapons that were used had changed, technology having provided weapons of mass destruction to the Nazis which were beyond Napoleon’s wildest dreams, but the pride of both Napoleon and Hitler was essentially the same. Militarism is still militarism, irrespective of the weapons being used, and imperialism still rides roughshod over the territorial rights of peoples, irrespective of whether it is pursued with swords or drones. These political philosophies, rooted in pride, neglect the dignity of the human person with destructive consequences.

All sin neglects the dignity of the human person, which is why history is decidedly undignified! Insofar as we perceive authentic dignity in human history, it is because we are perceiving authentic sanctity. It is the saints who add the dignified element to history. This is true of the past. It is true of the present. And it will be true of the future. The reason is that history does indeed repeat itself.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

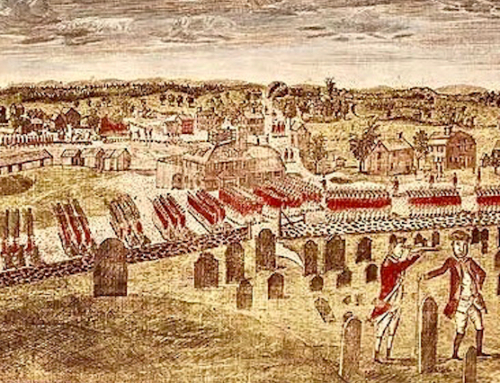

The featured image is “Bonaparte Before the Sphinx” (1886) by Jean-Léon Gérôme, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Of course, the author is absolutely correct with respect to the virtues and morals. As the Jews taught us 4000 years ago, some things are eternal, these things are absolute. And we ignore these eternal truths at our peril. But, I would also be a little more fair (to Chesterton). His quote “the sum comes out with a slight mysterious difference every time” is probably more correct than incorrect. It has been said that “No man steps in the same stream twice”. But a man steps in a “slightly mysteriously different” stream, which is located in the same place, but not the same time. So, Chesterton’s quote in my mind becomes not the “history repeating itself” but the slightly more accurate, and slightly more nuanced “history rhymes with itself”.

(p.s. I use the phrase “It has been said” because “I have forgotten who made this remark first”)

It was Heraclitus of Ephesus who said that one cannot step into the same river twice. Aristotle took Heraclitus very seriously (far more seriously than he took Parmenides and Parmenides’s disciple Xeno), but was much more skeptical of his students. He once said that, on this fella’s interpretation (of Heraclitus) you can’t step into the same river even once!

I’m with Chesterton on this. Sometimes history repeats itself and sometimes it doesn’t, and I would say for the most part it doesn’t. You say “history shows prideful choices preceding a fall, well, sometimes prideful choices do not proceed a fall. You pick Napoleon as your example. Alexander the Great was pretty prideful, and he did not have a fall. Generals Sherman and Patton were pretty prideful, and they didn’t have falls. And on the converse, General Robert E. Lee was fairly humble, and he didn’t win. No, you’re being selective in your data. Yes, sin has great consequences, and yet there are sinners that rise to great heights. Henry VIII, a despicable man in my opinion, never got the fall he deserved if go by his moral life. Sinners may rise, and sinners may fall. Virtuous people may rise, and virtuous people may fall. “For he makes his sun rise on the bad and the good, and causes rain to fall on the just and the unjust. (Matt 5:45).

However GKC felt about not being able to step into the same river twice in 1904, was surely tempered by the death of his brother Cecil in 1918. His worldview had undoubtedly been revised by reality when the nazi storm clouds were undeniably reforming over the continent in 1936 at the time of his death. His God given prophetic vision was a burden that, perhaps, his heart could not bear. Seeing europe tossed into the maelstrom again was a repetition from which he was spared.

It is less that history repeats then that humans repeat having forgotten previously hard learned lessons or choose to ignore them with the hubris that come from repeating to self that “this time it’s different”.

History repeats itself every time an essay is written about whether or not history repeats itself. The same objections and points arise.

What is missed in the responses is the nuance and contrast of definitions and meanings construed in the base words used in the arguing – “history” and “repeats”.

Do events and decisions occur exactly as they did every time before? Clearly not.

Do the outcomes generally mirror each other time and a gain? Obviously.

Are there exceptions to every rule when it comes to historical perspective? Of course.

It is human nature to focus on the trees when wisdom permeates the forest. And that repeats itself over and over and over again. But not in every situation.

Was it Mark Twain who quipped, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.”?

The Danish Lutheran historian, Kjersgaard, did an eminent television series in twelve parts, on the history of Denmark, which was blockbuster. Every episode ended with a cliffhanger, as if at this point Denmark might well have gone under (even in the twelth episode, with the cliffhanger being primeminister Jørgensen’s national debt) and Kjersgaard concluded his show with these anti-marxist words: “I can acknowledge no definite law in history.” Truly Lutheran, because if there is sin and law (confer hubris and nemesis), then there is also amazing grace, with religion.

Historical figures can be categorised and classified. Stalin, Bismarck, Palmerston, jahangir, Tito,Suleiman the magnificient were all empire-builders. Hitler, Mussolini, Saddam, Milosevic, Henry 6th, Napoleon 3rd all presided over the fall of empires