Part of the philosophy of “Dune” is that after a long and dark digital age, man must learn again to become self-reliant: to think and act as self-determined and self-reliant individuals; to be active participants in nature, not mere passive receivers of pleasure and pain. For that is the place of beasts, not men.

Dune is the movie for which I have been longing for years: a high-concept, meditative, science-fiction film that really makes you think about some aspect of what it means to be human. Directed by Denis Villeneuve, Dune satisfies that desire grandly, claiming its rightful place next to Blade Runner 2049, Arrival, and Interstellar as among the best science fiction films of the past decade. From its slow and meditative pace that keeps you clinging to every frame and hanging upon every musical note, to its stunning background sets, to the vividness of its characters, every major aspect of the film reflects the fact that Mr. Villeneuve thoroughly understands the heart of Frank Herbert’s original novel. In so doing, he has made a film adaptation of a book that will thoroughly delight both new viewers and long-time readers.

Dune is the movie for which I have been longing for years: a high-concept, meditative, science-fiction film that really makes you think about some aspect of what it means to be human. Directed by Denis Villeneuve, Dune satisfies that desire grandly, claiming its rightful place next to Blade Runner 2049, Arrival, and Interstellar as among the best science fiction films of the past decade. From its slow and meditative pace that keeps you clinging to every frame and hanging upon every musical note, to its stunning background sets, to the vividness of its characters, every major aspect of the film reflects the fact that Mr. Villeneuve thoroughly understands the heart of Frank Herbert’s original novel. In so doing, he has made a film adaptation of a book that will thoroughly delight both new viewers and long-time readers.

The film’s cinematography follows the focus of the original novel in two distinct but related ways. There are shots that portray the beauty—nay, the sublimity—of the natural landscape, and there are shots that portray the awesome power of what mankind is able to construct. These two things form a contrast, yes, but also a similarity. The majesty of the natural world is, as I said, sublime. That is to say, it is awe-striking, absolutely terrifying, soul-shaking. It produces in the viewer, whether that be the audience or the contemplative figure who occupies the rest of the shot, feelings of wonder and fear. Yet, as the movie cajoles us frequently with its litany of fear, ‘we must not fear, for fear is the mind-killer’ and the purpose of these glimpses into the grand power of nature are meant to make us think, to make our minds live, not die. What then are we to make of this feeling of fear, this sense of terrible danger lurking just behind the rays of the sun that tries to steal our precious water? We must transform it.

This, indeed, is one of the lessons that book and movie alike offer us, for through his journey, the main hero, Paul, learns neither to scorn the natural world nor to fear it, but to respect it, to flow with it and become part of it. This is indeed one of Frank Herbert’s major world-building points in his books; in order to really master nature, one must care for it, respect it, become part of its natural cycle and, as a gardener, direct those cycles to yield ever-greater fruits. Such are the goals of the Fremen, and such purpose is, in part, why they are such a powerful force on their planet. Besides this lesson, which Paul learns as part of his hero’s journey, these awe-inspiring shots of the natural landscape accomplish one more thing: They spur us on to think. And not just us, but the characters in the world as well, for there are many shots and scenes of the main characters staring off into the natural world and contemplating their mortality, their purpose, or even simply their difficult situation. Book and movie both, for instance, portray a moving scene between Paul and his father the Duke Leto talking as father and son under the stars. It is poignant to note here that the villains of the film never step foot from their man-made machines; there is not a single shot of one of them deigning to step on land and enjoy an open sky.

That isn’t to say that the artifices of man don’t have their own special place in the film, though. Indeed, the movie uses many intricately-crafted background set-pieces to give the audience better insight into the world of Dune and the temperament of its main characters. House Atreides are the living embodiment of the classic western ideal of a truly noble aristocracy, something one might find in Homer or Shakespeare, where virtue and honor meet wit and cunning to create something truly heroic. And deadly. The background pieces of the movie, though they often act as a memento mori, for the Atreides family, reinforce these facts in clever and insightful ways. The first part of the movie takes place on Calladan, the homeworld of House Atreides, a land covered in forests, lakes, and misty mountains. On this planet, in a scene where Duke Leto and his son discuss leadership, responsibility, lineage, and the passing on of duty from father to son throughout the ages, tombs and gravestones dot the land. The family graveyard. They are discussing lineages and the passing on of power from father to son in the family graveyard as they are waking away from a visit to Paul’s grandfather’s tomb. Though such a backdrop for this discussion is interesting and informative in itself, the markings and depictions on the tombs adds an even deeper layer; the tombs are covered in carvings that look nearly exactly like classical Grecian friezes, like those on the Parthenon depicting the Greek gods and heroes of myth battling giants and monsters. Not only does this detail add great beauty to the scene, but it also enforces just how classical the Atreides family is. It is no coincidence, the movie asserts, that this noble family bears the same name as the brothers Agamemnon and Menelaus, for they too have a noble bearing, and they too may suffer tragic ends. What makes this scene yet more astonishing is the fact that it is entirely original to the movie. There is no scene in the original novel that has anything like this scene in the old family cemetery. Though this is by far my most favorite example of the fine detail and deep thought that was lovingly poured into this movie, it is far from the only one.

These hidden depths are one of the primary reasons the film is such an excellent adaptation of the novel. Through these depths, easily open to the wary and curious mind, the movie lets each member of the audience take away exactly as much as he wishes from it. To the avid Dune reader watching the film with an attentive eye, all these details show that the filmmakers are equally big fans of Dune; and though they had to make certain cuts for the sake of film-time, they clearly did their best to convey everything that was necessary by other means. After all, Frank Herbert didn’t write three albums’ worth of soundtracks for his book (the stunning soundtrack was composed by Hans Zimmer); he didn’t design art and architecture that would reflect each unique culture in his world; he didn’t even explain in detail what his ships looked like. The film gives all this with an attentiveness and love that cannot possibly be feigned.

The average viewer, meanwhile, if he is attentive and clever, also picks up on many extra things the film does not tell the audience outright. He too is able to take what he wants from the film, and he too is able to enjoy the film immensely, for what does he have before him but a big-budget sci-fi film about rival political factions, mind-control, sword-fights, and giant sandworms? And who can’t enjoy watching that?

There are many more things I could say about this movie, but it is fitting to end my review with this: Part of the original Dune’s philosophy was that after a long and dark digital age, and many other trials and tribulations, man would learn again to become self-reliant. To wield great technological power at his fingertips, yes, but manually. No autopilots, no artificial intelligences, nothing. Just a man, his wit, his will, and the forces he must contend with. In trusting in their audience to be attentive, to be wary and appreciative, and from this to generate legitimate love for the movie, the film shows that it acts on this philosophy it presents, prompting the audience throughout the film to be like the main characters, to think and act as self-determined and self-reliant individuals, to be active participants in nature and the world around us, not mere passive receivers of pleasure and pain.

For that is the place of beasts, not men.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

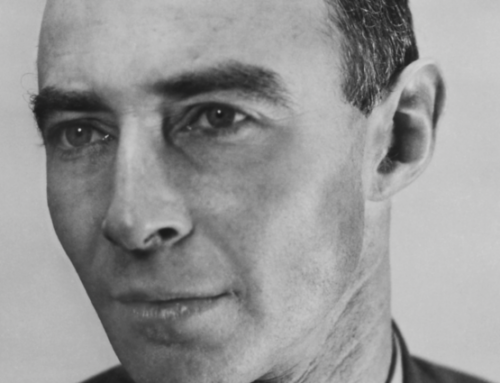

The featured image is courtesy of IMDb.

Excellent!

The most astute, soulful appreciation of Dune 2021 I’ve encountered thus far. The western Greek heritage was addressed, the central Asian and Islamic influences less so. Still the review evoked in me a more refined appreciation of the human/nature relationship and human transcendence suggested in the movie. Many thanks .

What a truly wonderful review. I loved both Frank Herbert’s books and the Villeneuve movie, talked about it with my daughters (one of whom is as keen on Herbert as I and all of whom loved the movie) and was very much taken with the movie’s love for the material and majesty. And this review brings out facets of the film that I had not even thought about (such as how the scene between Paul and his father is “artistic license” – but also a wonderfully creative way of illustrating the ties between father, son and their people), so this review to my mind is near perfect. I see the movie better now thanks to your writing.

I was worried that too much of the novel wouldn’t be able to translate well to theater screens; but Villenueve really outdid himself!

The only criticism I have is that Herbert’s theme of man adapting to life without computers wasn’t mentioned at all: The Butlerian Jihad and the ban on “thinking machines” is so key to understanding why this universe lives like it does.

Without this background, so many story elements like the Bene Gesserit stop being impressive examples of man’s capacity for self-mastery…

The movie alone is no substitute for the book, but they go excellently together.

“The average viewer, meanwhile, if he is attentive and clever, also picks up on many extra things the film does not tell the audience outright. He too is able to take what he wants from the film…”

Your review really nailed it. This film was incredibly meditative, and rich; a good example of style communicating substance. And, what i was thinking when I read the quote above, was how much this aspect of the film reminds me of traditional Latin or Greek liturgy. So much is there, but you are free to take what you want from it, and go deep, or tread upon the surface.