The beauty contest illustrates the difficulty with the term for and maybe the very idea of gentlemanliness—are good and beautiful two criteria or one? If they are two, how are they related? Could the beautiful be whatever compellingly attracts? Furthermore, what is truly and justly compelling?

Editor’s Note: This essay is part of a series dedicated to Senior Contributor Dr. Eva Brann of St. John’s College, Annapolis, in this, the year of her 90th birthday.

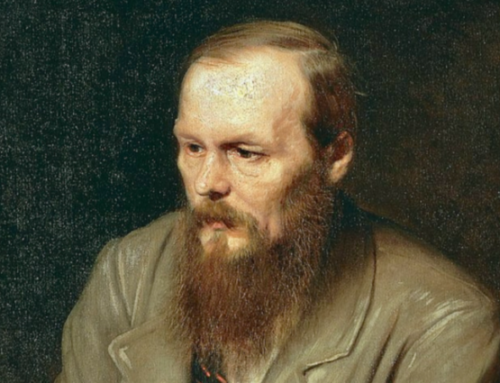

Plato’s dialogues provide most of what we know of the philosopher Socrates. Xenophon’s works offer the reader another perspective through which the extraordinary character of Socrates is visible. I offer no opinion on whether the two author’s presentations are fully consistent. Xenophon presents Socrates in contexts that appear more ordinary. In his Symposium, unlike Plato’s, we find men whose characters resemble figures in our own experience: there is, for example, no recently victorious poet to celebrate, and no brilliant political figure bursts in on the scene. It is a party for gentlemen, the kaloi k’agathoi, literally the noble (or beautiful) and good. As do leaders in every time and place, they think themselves better than their entertainers, and better than most of their fellow citizens. The dialogue illuminates the problematic meaning of their claim.

Xenophon opens his Symposium with the claim that the playful deeds of gentlemen are worth recording, implying that at least some of the participants in the dialogue are worthy of the epithet. But what does it mean to be a gentleman? The Greek term translated “gentleman” is kalos k’agathos, literally “noble (beautiful) and good.” The combination must be rare. It is not clear to what extent or how the good and the beautiful or noble can be combined in a man or in any being. What it means to be kalos k’agathos is a persistent but tacit question throughout the dialogue.

The setting of Xenophon’s dialogue is the home of the wealthy Kallias, who is throwing a party to help him win the favors of Autolycos, a young man who has just won an athletic contest. Autolycos’s father Lycon is there as well, along with a number of other guests that include Socrates and four of his companions. In Chapter One Xenophon describes how Autolycos’s beauty affected every soul of those who beheld him. Someone, Xenophon says, would have held that “beauty is something regal (basilikon) by nature (1.8).” He doesn’t simply say so himself. He does say that Autolycos combined with his physical beauty bashfulness and moderation, which contributed to the effect he made. The moderate Eros was apparent in Kallias in particular, giving him eyes that suggest kindliness and a general attitude of liberality. There is, then, another sort of Eros whose effects may not be so charming. In the course of the dialogue visible beauty and the virtues of character are in danger of being separated, exposing the veneer of conventional gentlemanliness. The separation may allow each of the two to be seen more clearly. If gentlemanliness is mere convention, such exposure runs the risk of exacerbating the problem whether the kaloi k’agathoi, the (true) gentlemen, can exist at all.

Xenophon’s presentation of Kallias is ambiguous, and it is clear that he and Socrates do not admire one another: Kallias seems to think Socrates and his companions, with their “purified” souls, will set a good tone for his exploits—they will make the setting more “resplendent (lamproteron)” (1.4)—but he does not share in their ways. He has studied with the sophists; Socrates and his companions are “self-taught (autourgos) in philosophy.” Before the party begins, as Kallias invites Socrates and his companions, he boasts that he can “say many wise things” and claims that he will show that he is “worthy of great seriousness,” (I, 6). Despite this lure (or challenge) Socrates demurs when Kallias first invites him. He accedes, evidently, to avoid Kallias’s “annoyance (achthomenos).” It soon becomes clear that Socrates finds Kallias’s intention with respect to Autolycos unsavory. The events and the dialogue of the party are a contest between Socrates and Kallias for Autolycos’s good and his good will. In the end Socrates appears to win this contest, at least temporarily, for in chapter eight, in the most extended and serious speech of the work, he persuades Kallias that he must do fine or noble things in Athenian politics if he is to win over Autolycos, who cares about noble things. But much happens before Socrates can take command of the partygoers enough to make his speech.

Far from showing his wisdom, as soon as the party is underway Kallias pulls out all the stops to display the sensual delights that his wealth can supply. Socrates successfully draws the line when Kallias offers to bring in perfumes to add to the delights of food, drink, laughter and entertaining dancers. If Kallias is indeed moved by the moderate Eros, it may be a temporary effect of Autolycus’s character and physical attractions combined. Kallias is not discriminating, as his offer of perfumes indicates. He willingly uses his wealth to obscure the discrimination of his guests. Socrates resists: by making all smell alike, Socrates says, perfumes obscure the difference between free and slave. As for the young and free, Socrates thinks they should smell as they do in the gym, of olive oil. He claims to know that the women find the odor appealing. It is no doubt an acquired taste but one that befits the wives of potential defenders of the city. Lycon, Autolycus’s father, speaks up for the older men: of what should they smell? Socrates claims that older men should smell of gentlemanliness (2. 3). If Kallias doesn’t interfere, perhaps Socrates can train noses.

By the beginning of chapter three Socrates has taken charge of the proceedings: first suggesting that “it would be shameful” if the partygoers won’t try “to benefit or delight one another,” he demands that Kallias make good on his earlier promise. This provokes Kallias to challenge each man to say what good thing each one knows. As for himself, he claims that he makes men better by teaching them gentlemanliness, “if justice is this” (3. 4). It turns out that he does so by giving them money (4. 1). There are a variety of other claims, having to do with wealth, poverty, friends, and the works of Homer. Socrates is proud of his art of pimping, which would make him wealthy if he practiced it (3.10). I will focus only on one other claim, that of Critobolus, the son of Crito.

Reasoning from his experience with respect to the absent Cleinias, Critobolus asserts that his own beauty is a great good, advantageous to others in its ability to make them “better.” For he “would even go through fire with Cleinias, and I know you would with me as well.” (4.16) Without seeing any problem with the claim, he says that he “would with greater pleasure be a slave than a free man were Cleinias willing to rule me….” (4.14). Critobolus’s sense of the good for human beings doesn’t require freedom, although it does include acts that may be considered “fine” or “noble” (i.e., kalon, the same word translated elsewhere as “beautiful”). Are these acts excellent? Are they good (agathos)? Kallias and Critobolus claim to have similar effects on others, and both claims are suspect. Socrates defends Kallias against the charge that the recipients of his largesse are unjust towards him and therefore not just at all by comparing him with the prophets who can’t prophesy about themselves (4.5). The defense is equivocal: just as prophets may not understand the messages they convey, Kallias may know nothing about justice. Socrates engages directly with Critobolus’s claim when he says he can win kisses more easily with his beauty than Socrates can with many wise sayings (4.17). Socrates retorts: “Do you make such claims on the grounds that you are even more beautiful than I (4.19)?” The beauty contest ensues.

In chapter five of the Symposium, Socrates, with his crab-like eyes and ass’s lips, is “proved” to be more beautiful than Critobolus, a young man known for his good looks and erotic passion. Critobolus and Socrates agree in speech that Socrates’ beauty prevails. The outcome in deed of the contest is, not surprisingly, different: the votes are all cast in favor of Critobolus, and it is presumably he who receives the kisses that were set out as a prize. Socrates objects that Critobolus’s money corrupted the judges (an indirect barb meant for Kallias?). If so, Critobolus’s ‘money’ consists in his physical attractions. These may indeed pose a danger of corruption to him and to others. But is the speech in defense of Socrates’ beauty more just?

It is pleasant to think that physical beauty is simply a delight for humans to behold, without necessarily endangering one’s judgment or the decency of one’s acts. But Critobolus is revealed elsewhere in the Symposium to be nearly incapacitated by erotic desire for another young man, Cleinias. Socrates has, he reports, been charged by Crito, Critobolus’s father, to loosen the hold of erotic passion on his son (4.24). It is not clear that he succeeds.

In the beauty contest proper, the central argument is that beauty involves utility, an undeniable if incomplete good. Socrates begins by asking whether only humans are beautiful. The obvious answer is no and Critobolus says it. He goes on to offer the examples of the horse and the ox, and the shield, sword and spear: these are beautiful, he says, “if they have been well wrought with a view to the tasks for which we acquire them, or if they’ve been adapted by nature with a view to the things we need….” (5.4) Critobolus accompanies this assertion with an oath “By Zeus.”[1] Well may he swear: one might object, though no one does, that a draft horse is almost always less beautiful than a race horse or even a wild horse. What is Critobolus thinking of? Is he simply enjoying the opportunity to give Socrates the chance to say ludicrous things? It is not rare for participants in beauty contests to say foolish things, and they look good while saying them; perhaps Critobolus is no different. Or was he trapped into associating the beautiful with the useful as soon as he allowed Socrates to question him? If he says the beautiful is useless and well-proportioned how can he maintain, as he did earlier, that it makes people good? Socrates, by trying persistently to remind the partygoers of a good beyond pleasure, and Critobolus, with his physical beauty, each represent one of the two elements of the gentleman. In the speeches of the contest they are mixed. For the time being, the effect of the mixture on the audience is invisible.

Speech or reason, logos, is not the most obvious medium for evaluating the beautiful. We are accustomed to relying not only on the pleasures of our senses but on differences of taste in judgments of beauty. Nonetheless we are often disconcerted when others are not moved by the same appearances, and some aver that “good taste” can be cultivated, by experience and the development of a vocabulary in which to express that experience. If there is something to be said about what makes an object beautiful, does Critobolus’s claim approach the mark? This at least is true: a denial of his claim involves rather serious difficulties, for a badly proportioned horse is sought neither for its beauty nor its utility; and a spear made of plastic would excite no one’s admiration. Socrates is correct in suggesting that eyes that don’t see or lips that neither kiss nor speak would not be in the fullest sense kalos. The standard may be correct even if Socrates’ crab–like, far set eyes are not lovely. Critobolus might have said that his own eyes allow him to see more as a man should.

But how should a man see? Socrates and Critobolus do not address the obvious question whether there is a particular utility for human eyes, or for a man in particular and therefore for his attributes. (Are eyes that can see beauty more beautiful than those which do not?) A man who is like a beautiful young horse in appearance might have a kind of beauty, but not the beauty appropriate to his kind. When Homer has Odysseus compare Nausikaa to a young tree, it is not perhaps the highest praise for a woman (Odyssey VI 161-169). But if human beauty is derivative from a peculiarly human end, how does one discern that end? There are a variety of candidates.

The outcome of the beauty contest in Xenophon’s Symposium allows the partygoers to settle for the time being for the answer that the only end worth pursuing is to delight. The contest itself, a charming diversion that forms a part of the entertainments of the evening, is playfully absurd. No one in their right mind (or with clear sight) would choose Socrates as the more beautiful of the two men, as seen by the light of the lamp. But Socrates is not simply being a buffoon; he has a reason for subjecting himself to such a humiliating comparison.

The beauty contest illustrates the difficulty with the term for and maybe the very idea of gentlemanliness—are kalos and agathos two criteria or one? If they are two, how are they related? One can easily think of men and women of distinction who are not good and good people who are undistinguished. Are these standards generally at odds with one another? It would be unsettling if there were a necessity for the fine and noble to be not-good and shocking for the good to be revoltingly ugly. But then Socrates too has his charms, and Critobolus himself delights not only in winning the kisses of others but in conversing with Socrates. Could the beautiful be whatever compellingly attracts?

Many followers attend Socrates, and it is not clear how many see him clearly. They follow him for a variety of reasons, and some are undoubtedly more welcome to Socrates than others. Whatever they see in him must differ from the conventional lures of physical beauty, wealth, and worldly honor. His attractions evidently include a kind of unabashed honesty—Socrates is entirely willing to have his eyes, nose, and lips, even his paunch, examined in the light of a lamp next to the charms of a beautiful young man. Socrates is honest, too, about the unanswered questions that beg for consideration. Whether beauty is good and whether the good attracts compellingly are two that cannot be ignored.

In the Symposium Xenophon implicitly raises these questions; he never makes them thematic. They are inseparable from the characters who live with and live out the difficulties the questions don’t fully capture. In this work they are raised playfully, and it is in play perhaps that they are most visible. Socrates’s self-deprecating performance in the Symposium permits him to strip away the pretenses of the wealthy, the physically beautiful and the simply distracting (the hired performers) to display the real issue: what is worth pursuing seriously? The question is not academic, and Xenophon presents it dramatically. His Socrates, immersed in the society of imperfect men, challenges their prejudices. He offers to educate them, too. Of course, the efforts of the Syracusan dancing master have a more immediate effect.

The Symposium ends with a display of beauty set in motion by eros. Earlier Socrates pointed out that the dancing boy, who is beautiful at rest, is even more beautiful when in motion (2.15). Immediately preceding the final erotic display Socrates makes a lengthy speech, addressed to Kallias. In it, he promotes friendship based on love of the friend’s soul instead of erotic attachment to bodies (ch. 8). Despite the playful, drinking party atmosphere of most of the dialogue, this speech is altogether serious. It is as close as we get in Xenophon’s Symposium to the ladder of love Socrates claims to have learned about from Diotima in Plato’s work of the same name. In his speech, which Socrates acknowledges may be thought too serious for the occasion, Socrates makes the case for Kallias to turn towards political ambition while discouraging him from seeking bodily satisfaction from his beloved. Socrates can’t or doesn’t suppress the speech, for he is moved by “…the Eros that always dwells with me and goads me into speaking freely regarding the Eros that is its opponent” (8. 24). Socrates too is in motion: he is no less moved by love than Kallias, and his sort of love elevates or at least distinguishes the high from the low. He is, he asserts, “a fellow lover of those who are by nature good and who seek out virtue ambitiously” (8, 41). Ambition or love of honor (philotimia) characterizes the noble. Although virtue is not an explicit topic of discussion in earlier chapters of the dialogue, it now appears that virtue and perhaps virtue alone combines the good and the noble. This much is clear: for Socrates what is truly fine, noble, or beautiful (kalon) is of compelling importance, whether or not the young athlete, or his would-be lover, has thought of it. Autolycus’s father Lycon at least seems to appreciate Socrates’s intervention (9. 1). But then again Lycon’s praise of Socrates may contain an ambiguity: he calls him a fine and noble, or gentlemanly human being rather than a real man (kalos k’agathos anthroposrather than aner).[2] Lycon didn’t object to attending the symposium in his son’s honor. He presumably wants the best things for his son but hasn’t ruled out that the best can be bought by Kallias’s wealth. Socrates’ contributions to the dialogue show that what is good demands careful examination. One might have thought beauty was more straightforward, but even that is unclear: while some are compellingly attracted to Socrates’s wise sayings, most are not.

In the final chapter the boy and girl performers Kallias has hired pose as Dionysus and Ariadne, and in doing so they move the rest of the married partygoers to rush home to their wives. Socrates, though married, remains with the unmarried men. Socrates has become friends of a sort with the Syracusan earlier in the dialogue (ch. 7). He seems to have become influential in the affairs of Kallias who, despite his earlier boasting, is no match for him. Socrates’s mastery of the situation he finds himself in at Kallias’s house is unmistakable. So too is Xenophon’s implicit defense of Socrates against the charge of corruption. If anyone is, the wealthy Kallias is the true corrupter of youth. Socrates does his best to mitigate the effects of Kallias’s seductive display not only on Autolycos. Not his eyes or lips but his speeches are compelling. But Socrates is not merely a member of the little society of partygoers who distinguishes himself.

Earlier in the dialogue Socrates attributed to himself pride in the art of pimping which he does not practice. He willingly gives over this art to one of his followers who, he implies, can gain wealth as well as gratitude by practicing it. One might think the art of pimping (or procuring) would be beneath the dignity of a gentleman, but here it appears more worthy of respect than many other arts. And yet Socrates fails to practice it and to earn a comfortable living for himself. What is it that compellingly attracts Socrates and lures him away from ordinary pursuits? In the beauty contest Socrates exposes the defects that repel some from him and draw them to the likes of Critobolous, and in doing so he highlights both the undeniable, physical truth and the less discernible deeper question, what is truly and justly compelling? The conclusion seems unavoidable that it is love of a good that is entirely compatible with poverty, bulging eyes, thick lips, and a paunch. Socrates is not only a lover of the good; he is also a defender of its pursuit. If such a defense is noble, Socrates is a true gentleman, both kalos and agathos.

Virtue and in particular the virtue of Socrates illustrates that the good and the beautiful can come together, but not in a class of men and not permanently. They come together in the genuine pursuit of the good. While bodies at rest may be beautiful, complacent souls are not. But the beautiful must be visible to be at all. In the Symposium Xenophon makes visible the beauty of Socrates’s pursuit of the good.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics as we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Editor’s Note: The featured image is the first version of “Plato’s Symposium” (1869) by Anselm Feuerbach (1829-1880), courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Leave A Comment