Why is the true Fourth such a powerful image of liberty? Because the things that most deepen us and rouse us are dangerous. An appetite for the real good means being willing to face danger, and the whole point of the liberty we celebrate is that we learn to handle danger, to face it responsibly, with care and virtue.

Most places these days treat the Fourth of July as a strangely anachronistic holiday—a celebration of liberty (didn’t we get rid of that?) when what we really need is more regulation, more laws to protect us from our own dangerous predilections. The Fourth of July in Lander, Wyoming, is an exhilarating exception.

Most places these days treat the Fourth of July as a strangely anachronistic holiday—a celebration of liberty (didn’t we get rid of that?) when what we really need is more regulation, more laws to protect us from our own dangerous predilections. The Fourth of July in Lander, Wyoming, is an exhilarating exception.

I could write about the rodeo, where children can walk around freely and nobody worries. (Some of them are even in the rodeo, riding bulls.) Dr. and Mrs. Scott Olsson’s daughter Josefina won the foot race for her age group by about twenty yards, by the way. Or I would write about the parade—a celebration of local veterans, class reunions, tribal identities, businesses, candidates, and so on—emceed by our own Gary Michaud and ending in a huge, more or less Dionysian huddle of fire engines turning all their hoses into the air at once. Younger citizens, including WCC students and their PEAK charges (not to mention a few alumni), frolic in the spray. But it’s the fireworks, which start at dusk and go on and on, that truly define the Fourth and give the most compelling image of American liberty, whose vital quality we’ve almost lost in the nanny state.

My wife and I have six of our grandchildren visiting this week, and it’s hard to describe their pure elation as darkness fell and we broke out the sparklers, the “snappers” that explode when you throw them on the ground, the (somewhat disgusting) “grow worms,” and then a whole string of firecrackers. Yes, it’s dangerous, sort of, all those little kids whirling fire around and making noise, but that’s the whole point. They couldn’t believe they got to do it! Private fireworks have been abolished where they live.

But the real revelation came when we piled everyone into cars and drove the five miles into Lander. As soon as we came over the last rise, we could see explosions all the way to the horizon. Everybody was setting off fireworks. Here’s what I wrote the next morning in a letter to friends: “It was like going through a happy war zone—explosions, the smell of smoke, loud cries. And the police, far from quashing this display, sat benignly by in case anything went wrong. It went on late into the night.” When we got back home, my oldest granddaughter (almost 11) said, “This is my first real Fourth of July!” It’s as though she’d always sensed what the celebration was supposed to be.

Why is the true Fourth such a powerful image of liberty? Because the things that most deepen us and rouse us are dangerous. The attempt to abolish all dangers turns us into what C.S. Lewis calls “men without chests.” An appetite for the real good means being willing to face danger, and the whole point of the liberty we celebrate is that we learn to handle danger, to face it responsibly, with care and virtue.

How many things in our culture, from contraception to gun control, stem from the fear that liberty will lead to our ruin? What we need is an education in the powers and dangers that come with our full participation in being human. Our real powers need liberty as fire needs air. Where could Wyoming Catholic College be except in Lander?

Republished with gracious permission of Wyoming Catholic College’s Weekly Bulletin (July 2016).

This essay was first published here in July 2019.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

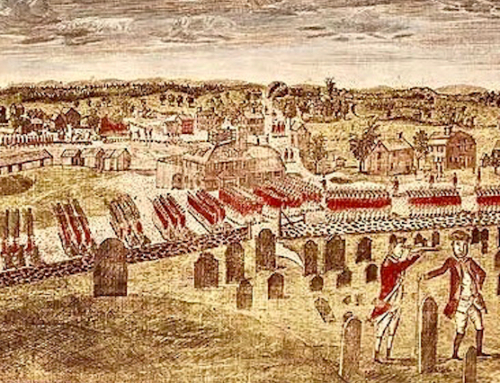

The featured image is a detail from Spirit of ’76 (1912) by Archibald Willard (1836–1918) and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. It has been brightened for clarity.

Leave A Comment