Winston Churchill’s education deserves close study because it shaped his evolution from unsteady boyhood to rational statesmanship. It was this education that enabled him to exercise discernment and discover what was advantageous and disadvantageous, just and unjust, so that—whether in peacetime or in war—he could demonstrate remarkable qualities and serve the country he loved.

Churchill stood at a crossroads. When his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, died in 1895, the twenty-one-year-old son had a choice to make. Either he would live as “the wastrel his father had accused him of being,” or he would make a name for himself.[1] Churchill chose the latter path. As a soldier, he survived the heat of battle and escaped capture during the Second Boer War (1899-1902). As a writer, he penned fifteen books, countless essays and newspaper articles, and eventually won the Nobel Prize in Literature. As a public servant, he served in parliament for sixty-four years and was appointed to ten ministerial positions including Chancellor of the Exchequer—formerly held by his father (1886)—and Prime Minister on two separate occasions. And as a statesman, he made extraordinarily difficult decisions which saved Great Britain during the Second World War (1939-1945).

Churchill stood at a crossroads. When his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, died in 1895, the twenty-one-year-old son had a choice to make. Either he would live as “the wastrel his father had accused him of being,” or he would make a name for himself.[1] Churchill chose the latter path. As a soldier, he survived the heat of battle and escaped capture during the Second Boer War (1899-1902). As a writer, he penned fifteen books, countless essays and newspaper articles, and eventually won the Nobel Prize in Literature. As a public servant, he served in parliament for sixty-four years and was appointed to ten ministerial positions including Chancellor of the Exchequer—formerly held by his father (1886)—and Prime Minister on two separate occasions. And as a statesman, he made extraordinarily difficult decisions which saved Great Britain during the Second World War (1939-1945).

No one in Churchill’s early life could have predicted that the “lazy little wretch” would someday become one of the greatest men in world history.[2] After all, his school years were characterized by “an unending spell of worries,” and his efforts were then “uncheered [sic] by fruition.”[3] Hence, most accounts regard his education as “nearly a disaster.”[4] But when Churchill was appointed Prime Minister on the eve of war with Germany (1940), he reflected that “all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and for this trial.”[5] As a significant period of his life, Churchill’s education deserves close study because it shaped his evolution from unsteady boyhood to rational statesmanship. In the words of Aristotle, Churchill’s learning years cultivated his nature, habits, and reason in an unqualified sense. He became a true statesman later in life because he had already learned and grown through the trials common throughout his formative years.

As a boy, Churchill’s nature was ill-suited for the confines of school.[6] His contemporaries seemed, in every way, “better adapted to the condition of our little world,” and it was “not pleasant to feel oneself so completely outclassed and left behind at the very beginning of the race.”[7] Part of the problem was the clash between Churchill’s raw spiritedness and authority.[8] According to his first grade report (1882), Churchill was “a regular pickle” who had “not fallen into school ways yet.”[9] Instructors consistently reprimanded him for “his casual manner,” lack of ambition, and “still troublesome” behavior.[10] Another part of the problem was the routine absence of his parents. Not only did they send Churchill to four boarding schools—St. George’s (1882), Brighton (1884), Harrow (1888), and Sandhurst (1893)—but they often avoided him for months on end, whether in person or in writing.[11] Nevertheless, Churchill’s character improved over time. His development caught the attention of his betters.

Churchill’s schooling at St. George’s and Brighton witnessed his first embrace of hard work and discipline. He still behaved like any average child at first.[12] Yet Churchill was determined “to be a good boy.”[13] His teachers noticed. One headmaster remarked that Churchill was “beginning to realize that school means work and discipline.”[14] And while Churchill’s behavior was occasionally “exceedingly bad,” he was “notwithstanding [making] decided progress.”[15] Churchill’s momentum continued at Brighton. Inside the classroom, he demonstrated “decided improvement in attention to work.”[16] And when the term concluded, Churchill’s headmaster wrote an optimistic evaluation: “Very marked progress made during the term. If he continues to improve in steadiness and application, as during this term, he will do very well indeed.”[17] Upon Churchill’s move to Harrow, he faced new and greater challenges, however.

In a letter to his mother, Churchill expressed great distaste for Harrow.[18] Not only was he disciplined more harshly than before, Churchill still struggled to habituate himself to the school environment. The assistant master, H.O. Davidson, observed that while Churchill was not “willfully troublesome,” his “forgetfulness, carelessness, [and] unpunctuality” held him back from success. Churchill remained “regular in his irregularity,” and thus Davidson doubted Churchill’s fitness for any intellectually-driven task.[19] Yet at the same time, Churchill caught the attention of his peers not for his supposed ineptitude, but for his development. Murland Evans, an older classmate, observed that Churchill routinely demonstrated a “commanding intelligence,” “bravery, charm,” and a “vivid imagination.” His descriptive powers and knowledge “of the world and of history” were undisputed. No one knew how or where they came from. And while Churchill and his classmates were “under the severe repression” of the public school system, Churchill’s nature “dominated great numbers around him, many of whom were his superiors in age and prowess.”[20] Indeed, Churchill was “a remarkable boy,” but he still had a lot of growth ahead of him as he oftentimes reverted back to laziness.[21] In the following years, Churchill grew in maturity as he refined his habits.[22]

Heeding the advice of his parents and instructors, Churchill refocused his abilities both in and outside the classroom. While furiously preparing for the upcoming army preliminary examination, Churchill excelled in school.[23] He even enrolled in contests to challenge his memory: “I am learning 1000 lines of Macaulay for a prize [and] I know 600 at present. Anyone who likes to take the trouble to learn them can get one, as there is no limit to the prizes. Next term I am going in for Shakespeare.”[24] His aunt, the Duchess of Marlborough, was impressed: “I . . . Am pleased to see you are beginning to be ambitious!” She recommended that as a next step, Churchill should observe his father, “a great example of industry” and “thoroughness in work,” and model his habits in the days to come.[25] Churchill listened.[26] His success that year revealed the depth of his ambition. Under the tutelage of teachers who inspired him to embrace the rigors of the learning process, Churchill comfortably passed the preliminary examination in all subjects.[27]

But in 1892, Churchill first experienced the effects of failure. How he responded, however, demonstrated the exceptional growth of his character at the time. With the Sandhurst entrance exam approaching, Churchill devoted countless hours to his studies. He remained confident that his hard work would prove fruitful. Unfortunately, his initial attempts resulted in failure. Upon a third try his scores rose just enough to land him a position in the cavalry. Churchill was elated. He had finally surmounted an examination that consistently bested many students across the country.[28] There was only one problem. Although he had applied himself to the best of his abilities, the prior academic trial paled in comparison to overcoming his then abysmal standing in his father’s eyes.[29]

Lord Randolph was furious. Not only was he embarrassed—“[Winston] has gone & got himself into the cavalry who are always 2nd rate”—but Churchill’s performance seemed to confirm what Lord Randolph had believed all along. His son’s alleged advancements had produced nothing but “great slovenliness of work.”[30] Lord Randolph could perceive no outcome where Churchill redeemed himself from insufficiency. He would become “a social wastrel,” “one of the hundreds of the public school failures.”[31] While his father’s criticism could have altered the course of Churchill’s life for the worse, had he surrendered to despair, Churchill’s response spoke volumes.

Rather than dispute with his father, Churchill received his father’s criticism as a learning opportunity. Churchill strengthened his commitment to bettering himself. He promised “to try to modify” his father’s opinion “by my work & conduct at Sandhurst during the time I shall be there.”[32] This was an understatement. With determination and the ambition to succeed, Churchill proved that his father could not have been more wrong.

Churchill blossomed at Sandhurst. He later wrote in the Pall Mall Magazine (1896) that his time at the academy was “a period of gratified ambitions and of attained ideals.”[33] He became fascinated by his military studies, which in turn required higher levels of diligence and hard work than ever before.[34] Yet Churchill was up to the challenge. His instructors approved of his work and had “no definite complaints to make.” Lord Randolph likewise recognized Churchill’s ongoing advancement. After one of his rare visits, Churchill’s father wrote that “Winston is flourishing at Sandhurst.”[35] Over the next few years, Churchill achieved an excellent standing.[36] He had the privilege of passing the esteemed riding examinations and, most importantly, he graduated in the top fifteen percent of his class.[37] These were indeed commendable accomplishments, considering his past. But it was beyond Sandhurst that Churchill truly achieved excellence.

By the time Churchill deployed to India, his character had been molded by discipline and the fruits of well-directed ambition. Only his reason remained untrained.[38] As Churchill admitted in My Early Life, it was not until his twenty-second year “that the desire for learning came upon me. I began to feel myself wanting in even the vaguest knowledge about the many large spheres of thought.” Surrounded by liberally educated peers, Churchill reflected upon his own education and found gaps.[39] Whether at Harrow or even Sandhurst, his prior schooling had lacked the intellectual rigor, the “apt and copious information which” a university-trained man possessed. Now, in his bungalow in Bangalore, Churchill burned with a desire to learn about “the Socrates story,” and the lessons accompanying a discussion of great ideas.[40] Out of his own volition, Churchill resumed his education. He resolved “to read history, philosophy, [and] economics” in order to think for himself.[41]

The more Churchill studied—from Plato’s Republic to Darwin’s Origin of Species—the more he recognized the true value of formal education. Churchill realized that throughout his early life, he had adopted “a system of believing whatever I wanted to believe,” of “leaving reason to pursue unfettered whatever paths she was capable of trading.” These options were no longer available. With no teachers or guides to rely upon when faced with matters of truth and falsity, Churchill could not afford merely to devour books with “an empty, hungry mind.” He was alone. Hence, his “curious education” depended entirely upon the cultivation of discernment.[42]

The virtue Churchill discovered in this education was the ability to think for himself. He noticed that when his younger peers were introduced to philosophy, they had subsequently abused their knowledge by rehashing juvenile arguments proving “nothing has any existence except what we think of it.” Churchill, on the other hand, studied the same difficult ideas, but he formulated his own thoughts. He realized that while the undergraduate antics were “perfectly harmless,” they were also “perfectly useless.”[43] Although it might be a quaint experience to disprove reality as a show of braggadocio, Churchill discerned that in the end, the “metaphysicians will have the last word and defy you to disprove their absurd propositions.”[44] Churchill had spent his time in Bangalore, India, pursuing intellectual refinement through rigorous study. Indeed, his ambition and diligence had laid the groundwork for Churchill to cultivate his rational capacities in an unqualified sense. And as a result, he became accustomed to making difficult decisions, of exercising discernment during times when guides were nowhere to be found.[45]

From playing with toy soldiers to making state-decisions based upon a myriad of shifting circumstances, Churchill’s education had indeed prepared him for later, unfathomable trials. This is not to draw a strict correlation between Churchill’s success in school and his success as a statesman, however. He himself admitted that “no one [had] ever passed so few examinations and received so many degrees.”[46] Churchill’s academic standing was never preeminent, nor did he have the opportunity to attend university and study the science of politics. Nevertheless, it would be foolish to say Churchill’s education was extraneous to what he did later in life. He would not have become a statesman of unquestionable caliber had he not learned from the many challenges prevalent throughout his formative years. Those early trials taught Churchill the importance of diligence, ambition, and hard work. These, in turn, helped him discover a love of learning that enabled him to think beyond the mistakes of the past to solutions for the future.[47] But most importantly, Churchill’s education enabled him to exercise discernment and discover what is advantageous and disadvantageous, just and unjust. Whether in peacetime or in war, Churchill demonstrated these remarkable qualities when he served the country he loved.

In 1946, one year after the Second World War ended, the elder statesman spoke at the University of Miami on the importance of education in a post-war world.[48] Churchill observed that one of the unforeseen consequences of the war was the “young men [who had] their education interrupted” by the global conflict. He understood the magnitude of this problem. Education can transform lives as it did his own. Churchill was a “late-starter,” and he spoke to the other “late-starter[s]” of the world: “no boy or girl should ever be disheartened by lack of success in their youth but should diligently and faithfully continue to persevere and make up for lost time.”[49] With his life’s path on display before all, Churchill drew upon his experiences in the hope of helping millions. Although he had failed to stop the war, he could still chart a new path forward. It was time to resume “study of the philosophies, humanities and the great literary monuments of the past.” These could offer countless advantages to the many who had sacrificed everything.[50]

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Notes:

[1] Martin Gilbert, Churchill: A Life (New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, 1991), 49.

[2] The Churchill Documents: Youth 1874-1896, Vol. 1 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 1967), 364. The quotation was taken from a letter sent to Churchill from his mother.

[3] Gilbert, 34.

[4] Laurel King, “Winston Churchill Education Background,” Winston Churchill Collegiate Institute, November 6, 2013. See also Gilbert, 34: In 1930, Churchill admitted that while he was “all for the Public Schools,” he would “not want to go there again.”

[5] Gilbert, 645.

[6] Carnes Lord, ed. “Book 7, Chapter 13.” In Aristotle’s Politics, 2 ed., 217–18 (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2013), 218. Aristotle defines nature as how a man develops as a human being to obtain “a certain quality in body and soul.”

[7] Gilbert, 34.

[8] “Education of Winston Churchill,” National Churchill Museum, 1.

[9] The Churchill Documents, 90.

[10] Ibid., 371, 95, 92: “He has no ambition — if he were really to exert himself he might yet be first at the end of the Term.”

[11] Gilbert, 9,12, 88. Sir Martin Gilbert records that Churchill’s parents were less than forthcoming with the kind of love craved by a young child: “Back at Brighton for the autumn term, Churchill read in the local newspaper that his father had made a speech in the town. ‘I cannot think why you did not come to see me, while you were in Brighton,’ he wrote. ‘I was very disappointed but I suppose you were too busy to come. . . .’ That winter the son’s need for his father’s love was again disappointed.” On a different occasion, Churchill wrote to his mother, “It is very unkind of you not to write to me before this, I have only had one letter from you this term.”

[12] The Churchill Documents, 91, 92: Some commented that he did “not quite understand the meaning of hard work” and was often “very naughty.”

[13] Ibid., 86.

[14] Ibid., 93.

[15] Ibid., 94: “He cannot be trusted to behave himself anywhere. He has very good abilities.”

[16] Ibid., 98.

[17] Ibid., 99.

[18] Ibid., 194: “I hope you don’t imagine that I am happy here [at Harrow]. . . . Of course what I should like best would be to leave this [hell of a] place but I cannot expect that at present.”

[19] Ibid., 168-169.

[20] Gilbert., 23.

[21] The Churchill Documents, 168-169.

[22] See Lord, 218. Aristotle defines habits as certain qualities and decisions that mold one’s nature: “But there is no benefit in certain [qualities] developing naturally, since habits can make them alter: certain [qualities] are through their nature ambiguous, through habits [tending] in the direction of worse or better.”

[23] The Churchill Documents, 157: “I am working hard for my Examination. . . . We are getting through the 2nd book of Virgil’s Aeneid all-right, I like that better than anything else. I have done the 1st 30 Propositions in Euclid. . . . In Algebra we are doing L.C.M.’s. In English History the Saxon Period. In Ancient History the 2nd Persian Invasion & in Geography the Continents of North & South America. I hope I shall pass — I think I shall.”

[24] Ibid., 166.

[25] Ibid., 200.

[26] Ibid., 204.

[27] Ibid., 214.

[28] Ibid., 548: “The entrance examination is so difficult, and the competition so severe, that the great majority of young men who obtain cadetships come from the various ‘cramming establishments’ in London and throughout the country.”

[29] Ibid., 390. Churchill’s newly acquired standing was considered socially-inferior to the army. His father made Churchill well aware of this fact: “I [Lord Randolph] am rather surprised at your tone of exultation over your inclusion in the Sandhurst list.”

[30] Ibid., 386: Lord Randolph wrote that his son “has little [claim] to cleverness, to knowledge or any capacity for settled work. . . . In all his three examinations he has made to me statements of his performance which have never been borne out by results. Nothing has been spared on him; the best coaches every kind of amusement & kindness especially from you & more than any boy of his position is entitled to. The whole result of this has been either at Harrow or at Eton to prove his total worthlessness as a scholar or a conscientious worker.”

[31] Ibid., 390-391: “Never have I received a really good report of your conduct in your work from any master or tutor . . . Always behind-hand, never advancing in your class, incessant complaints of total want of application, and this character which was constant in your reports has shown the natural results clearly in your last army examination.” Lord Randolph also vowed never to “attach the slightest weight to anything” Churchill might say about his accomplishments.

[32] Ibid., 394.

[33] Ibid., 552.

[34] His studies included fortification, tactics, topography, military law, and military administration.

[35] Ibid., 420, 466. Lord Randolph encouraged Churchill to embrace his determination and pursue greater excellence: “when you go into the army I wish you to make your one aim the ambition of rising in that profession by showing to your officers superior military knowledge, skill & instinct.”

[36] This is not to say that Churchill’s life became any easier. In fact, Churchill continued to work through difficulties between himself and his father, most famously when Churchill lost a gifted watch while swimming and was forced to pacify his once-again enraged father.

[37] Ibid., 540-541: “The Riding Examination took place on Friday. . . . I am awfully pleased with the result, which in a place where everyone rides means a great deal, as I shall have to ride before the Duke . . . I hope you will be pleased. . . . The competition is very keen and I am working hard. . . . I trust it may be satisfactory and that I shall find I have passed successfully out of Sandhurst.”

[38] Lord, 218. Aristotle argues that above all, reason is most impacted by education: “The other animals live by nature above all, but in some slight respects by habit as well, while man lives also by reason (for he alone has reason); so these things should be consonant with each other. For [men] act in many ways contrary to their habituation and their nature through reason, if they are persuaded that some other condition is better. . . . What remains at this point is the work of education. For [men] learn some things by being habituated, others by listening.”

[39] Winston S. Churchill, “Education At Bangalore,” In My Early Life, 109–21 (Thorton Butterworth, 1930), 109: “I would have paid some scholar . . . to give me a lecture of an hour or an hour and a half about Ethics. What was the scope of the subject; what were its main branches; what were the principal questions dealt with, and the chief controversies open; who were the high authorities and which were the standard books?”

[40] Ibid., 110: “Some had used the phrase ‘the Socratic method.’ What was that. . . ? he was beyond doubt a considerable person. He counted for a lot in the minds of learned people. . . . Why had his fame lasted throughout the ages? What were the stresses which had led a government to put him to death merely because of the things he said. . . ? Such antagonisms do not spring from petty issues. Evidently Socrates had called something into being long ago which was very explosive.”

[41] Ibid., 110, 111.

[42] Ibid., 112-113: “I had no one to tell me: ‘This is discredited.’ ‘You should read the answer to that by so and so; the two together will give you the gist of the argument.’ ‘There is a much better book on that subject,’ and so forth.”

[43] Ibid., 113: “Now I pity undergraduates, when I see what frivolous lives many of them lead in the midst of precious fleeting opportunity. After all, a man’s Life must be nailed to a cross either of Thought or Action. Without work there is no play.”

[44] Ibid., 117.

[45] There are many examples of Churchill’s discernment in action, including his choice to refrain from using military troops to break up the Tonypandy Riots (1910-11), and his decision to pursue war with Germany as Prime Minister when British troops were being pushed back to Dunkirk (1940).

[46] Winston S. Churchill, “Education,” University of Miami, February 26, 1946, 1. Degrees are rewards, symbols of success and achievement in something.

[47] Winston S. Churchill, “The Munich Agreement,” Speech, House of Commons, London, October 5, 1938. Churchill opposed Chamberlain’s pact with Hitler because Churchill understood an unchanging truth: you cannot reason with a Tiger when you are in its mouth. He said, “there can never be friendship between the British democracy and the Nazi power, that power which spurns Christian ethics, which cheers its onward course by a barbarous paganism, which vaunts the spirit of aggression and conquest, which derives strength and perverted pleasure from persecution, and uses, as we have seen, with pitiless brutality the threat of murderous force. That power cannot ever be the trusted friend of the British democracy.”

[48] According to my teacher, Dr. Larry Arnn, “This is the difficult point: how did Churchill come to identify education in the way he did? Was it because he had no teachers in that corrupt age and had to figure it out for himself? Was it simply extraordinary ability?” I believe it was a combination of both. Given his upbringing, Churchill learned what he could from the teachers available to him. But it was also extraordinary ability—for any lesser man would have succumbed to the numerous obstacles thrown into his path—that allowed Churchill to understand the true value of education and its place in an ignorant world.

[49] Ibid., 2.

[50] Ibid., 3.

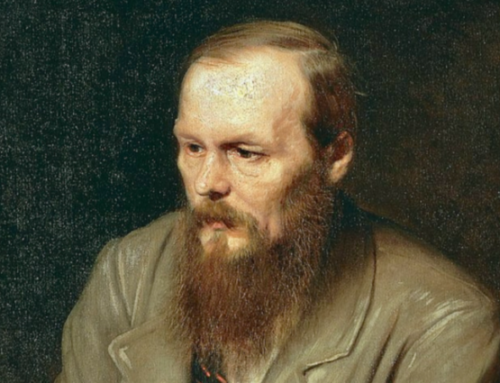

The featured image is a photograph of Winston S. Churchill at the age of seven (1881) and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

thank you