The loudest voices right now are exhorting us to “listen to the science.” And we should. But we would do well to listen also to the wisdom of our ancestors. For if science is what will get us out of the pandemic, it is the humanities that will help us flourish while we endure it.

Over the last year, pundits have commonly averred that we are living in “unprecedented times.” When this assertion is made with respect to the pandemic, it is often accompanied by declarations that we must “listen to the science,” since (as the reasoning goes) science is our best hope for getting back to “normal.” These claims are myopic and symptomatic of an ahistorical worldview that is excessively committed to the notion that scientific progress is the sole mechanism for promoting prosperity. We are in fact not living in unprecedented times. And while science is critical, science alone is insufficient for the cultivation of human flourishing in these challenging times.

Over the last year, pundits have commonly averred that we are living in “unprecedented times.” When this assertion is made with respect to the pandemic, it is often accompanied by declarations that we must “listen to the science,” since (as the reasoning goes) science is our best hope for getting back to “normal.” These claims are myopic and symptomatic of an ahistorical worldview that is excessively committed to the notion that scientific progress is the sole mechanism for promoting prosperity. We are in fact not living in unprecedented times. And while science is critical, science alone is insufficient for the cultivation of human flourishing in these challenging times.

The ancient preacher was right to say that “What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun” (Eccl. 1:9). History is replete with plagues and pandemics. Among many others, one recalls the plague of Athens in the late 5th century BC,[1] “Cyprian’s Plague” in the 3rd century AD,[2] the Black Death that decimated Europe in the late Middle Ages,[3] the plague that rattled London in the mid-17th century,[4] and the Spanish Flu in the early 20th century.[5] Importantly, when we study these plagues, we find that they bred problems much like the ones we presently face: physical and emotional suffering, grief, economic instability, social and political disarray, questions of whether and how to conduct schooling and religious observances, uncertainty over whether to gather with friends and family. Thus, while COVID-19 and its attendant problems may seem new to 21st-century westerners, the challenges we face are hardly unprecedented in the annals of history.

As for science, while it is obviously indispensable to our efforts to eradicate COVID-19, science alone cannot provide all the answers we need in this season. Science can tell us—indeed, has told us—how the virus spreads and how best to treat the sick. Medical professionals deserve endless credit for their selfless and Christ-like care of the sick and dying. Scientists have now even produced a number of safe and effective vaccines. These are major contributions for which we ought to give thanks. But while scientific knowledge does save lives, science itself cannot explain why we should care about the preservation of life and health in the first place. Science can reduce the pain of those who suffer, but it cannot teach us how to live well in a world in which suffering, loss, and disappointment are inevitable. Science can tell us that keeping six feet apart will mitigate the spread of germs, but it cannot help us cope with the loneliness that social distancing forces upon us. For these things we must look to the humanities.

The humanities are in the business of networking. They introduce people of one time and place to those of another so that individuals from different generations and cultures can have a discussion. This is why practitioners sometimes speak of studying the humanities as entering “The Great Conversation.” The Conversation is at its best, and is most nourishing, when it revolves around perennial and quintessentially human questions: for example, what is the purpose of man? What makes for a good life and a good death? Why do pandemics and other tragedies befall us? Does suffering have any purpose? How does God relate to suffering and sufferers? It seems to me that these questions are, or at least ought to be, just as important today as the questions that science can answer.

Those who are most qualified to help us answer such questions are our forebears who lived in circumstances like our own and who asked similar questions to the ones we are asking. It is to our benefit that there are many among them. Having endured challenges that are similar to those we face, they are equipped to lead us through our own trying times.

The fact that our predecessors faced similar problems to our own means that we are not alone in our suffering. By sharing in the sufferings of our ancestors, we have an invitation to fellowship with them and to learn from them.[6] To do so, though, we must unmoor ourselves from the tyranny of “now” so that we can give our attention to more enduring things, more nourishing things. In other words, we must make space for our ancestors, especially by putting down our screens and picking up old books.

Since last March, my students and I have spent considerable time discussing texts that document human responses to plagues, sickness, and suffering. We have reflected upon Thucydides’ account of the plague of Athens, Cyprian’s “Treatise on the Mortality,” Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy, Julian of Norwich’s Revelations of Divine Love, Martin Luther’s letter in response to the question whether Christians may flee a deadly plague, C.H. Spurgeon’s 1866 sermon on an outbreak of cholera, and Albert Camus’ The Plague. These are just a fraction of the texts that are pertinent to our current circumstances, but with just these few my students and I have been able to evaluate a variety of responses to sickness and suffering—all in dialogue with previous generations. In the process, we have contemplated our own mortality, reflected upon the orderliness of our fears and the substance of our hopes, and envisioned how we will respond when (not if) suffering and death come to us, whether through COVID or something else.

Implicit in our decision to listen to earlier voices is a conviction that our ancestors, even from their graves, can prepare us for the challenges we face. We do not have all the answers. If we are to flourish during these trying times, we will need guidance, hope, and purpose; we will need truth and wisdom that endure longer than our ephemeral existence in this world. We can glean these things in the writings and works of our forebears. Their wisdom is our inheritance, and they have bequeathed it to us for our enrichment and fortification.

If someone responds that the best place to find wisdom and hope for our times is actually in the word and works of God, I agree completely. But this does not render all other voices irrelevant. The Church has always affirmed, at least since Paul’s sermon in Athens, that there are truth, wisdom, and virtue to be found in non-biblical, even non-Christian, sources.[7] To acknowledge that supreme wisdom is to be found in God alone—for God is himself supreme wisdom—enables us to put human voices in their proper places. God’s wisdom is a touchstone for evaluating all other claims.

The loudest voices right now are exhorting us to listen to the science. And we should. But as we listen to the science, we would do well to listen also to our ancestors. For if science is what will get us out of the pandemic, it is the humanities that will help us flourish while we endure it.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Notes:

[1] Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, II:vii.3–54.

[2] See especially Cyprian of Carthage, “On the Mortality”. In addition to exhorting his flock to faith and sacrificial service amid the plague, Bishop Cyprian also provided a vivid description of the plague’s symptoms (ibid. §14). It is for the latter reason that the plague came to be called after him. See also Dionysius of Alexandria’s Eastertide letter to the Alexandrian church, which comments on the same plague (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, vii: 22). Dionysius notes that there was hardly a home in Alexandria that did not lose someone to the disease. For a modern assessment of “Cyprian’s Plague” and the Christian response to it, see Rodney Stark, The Rise of Christianity: How the Obscure, Marginal Jesus Movement Became the Dominant Religious Force in the Western World for a Few Centuries (New York: Harper Collins, 1997), 73–94.

[3] For an anthology of primary responses to the Black Death, see John Aberth, ed. The Black Death, The Great Mortality of 1348–1350: A Brief History with Documents (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2005).

[4] See Daniel Defoe, A Journal of the Plague Year, originally published in 1722. The book is almost certainly based on the diaries of the author’s uncle, Henry Foe, who witnessed the plague firsthand nearly sixty years earlier.

[5] See John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History (New York: Penguin, 2018 [orig. 2004]). For a recent work on how the Spanish Flu influenced literature, see Elizabeth Outka, Viral Modernism: The Influenza Pandemic and Interwar Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019).

[6] Hence the clever title of Alan Jacobs’ recent book, Breaking Bread with the Dead: A Reader’s Guide to a More Tranquil Mind (New York: Penguin, 2020).

[7] Acts 17:22–34. See also Basil the Great’s lecture, “To Young Men, on How They Might Derive Profit from Pagan Literature,” pages 182–88 in Richard Gamble, ed. The Great Tradition: Classic Readings on What It Means to Be an Educated Human Being (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2007).

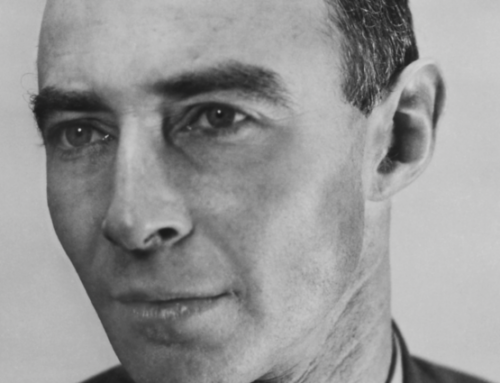

The featured image is courtesy of Unsplash.

Any who makes the claim that we must “listen to the science”, at the most fundamental level fails to comprehend science. Ironically, so-called scientists whose egos are larger than their curiosity. The true scientific mind understands that, in discovering the true nature of things, the scientific approach creates more questions then resolutions. A true scientist understands that the nature of discovery involves questioning one’s results, and debating the nuances that generally reveal more truth but, more than they would like to admit, there’s a twist or turn that changes everything they/we once believed.

The contrarian view that is belittled and berated by the most passionate believers of “the science” threatens, not the science, but the believers.

We are not witnessing the scientific method being applied to “the pandemic”. What we are witnessing is ego, hyperbole, confusion about conclusion, and the triumph of message over matter.

Media is little more than theatre these days. For me, finding humor in all the hypocrisy on display is about all that keeps me sane. “In an insane world, it is the sane man who seems insane.” ~Spock (he was a scientist, you know)

Science, human wisdom and anything human in nature can not help in these changing times. God alone is the answer what we must do is to pray to God so that the pandemic can be quenched.

Our wisdom and science can just diminish the issue. But God quenches it all. It is naive to believe and abide on science alone, we must keep our faith to God.

Thank you for your insightful and thought-provoking essay. I very much enjoyed it.

Covenant School, Huntington, WV is very fortunate to have you teaching Humanities.