Just as no person can last forever, no republic can last forever. The trick, however, to prolonging its life is to promote that which gives it energy and vigor in its youth—virtue—and that which also staves off the inevitable tepidness that accompanies mid-life: audacity.

No true republican believes that a republic lasts forever. Far from it. Republics reflect the organic order and natural law of the universe, and they mimic the three faculties of human understanding: the head/executive (rationality); the soul/aristocracy (reason/imagination); and stomach/democracy (the passions and the senses). As a reflection of the biological, the republic must also—as Polybius, Cicero, and Livy well understood—go through stages of birth, middle age (corruption and decay), and finally death. The process is the same for a human being as well as for a republic. Again, it must be remembered that just as no person can last forever, no republic can last forever. The trick, however, to prolonging its life is to promote that which gives it energy and vigor in its youth—virtue—and that which also staves off the inevitable tepidness that accompanies mid-life: audacity.

No true republican believes that a republic lasts forever. Far from it. Republics reflect the organic order and natural law of the universe, and they mimic the three faculties of human understanding: the head/executive (rationality); the soul/aristocracy (reason/imagination); and stomach/democracy (the passions and the senses). As a reflection of the biological, the republic must also—as Polybius, Cicero, and Livy well understood—go through stages of birth, middle age (corruption and decay), and finally death. The process is the same for a human being as well as for a republic. Again, it must be remembered that just as no person can last forever, no republic can last forever. The trick, however, to prolonging its life is to promote that which gives it energy and vigor in its youth—virtue—and that which also staves off the inevitable tepidness that accompanies mid-life: audacity.

At the end of his profound Radicalism of the American Revolution (Pulitzer Prize winner, 1993), Gordon Wood argues that with only one exception—that of Charles Carroll of Carrollton—all the signers of the Declaration of Independence believed that the American republic had already run its course. Interestingly enough, Woods is actually wrong about Carroll—who was as distraught over the state of the republic as any of the other founders.

Taking Wood’s overall argument seriously, political theorist Dennis C. Rasmussen has recently given us his deeply disturbing and wonderfully executed Fears of a Setting Sun: The Disillusionment of America’s Founders (Princeton, 2021). Not surprisingly, given Wood’s troubling claims, Rasmussen comes to a similar conclusion. Of the major founding fathers, only James Madison departed this world with hope for and in the future of the American republic.

Because they saw themselves as playing for history’s highest stakes, the founders were thoroughly absorbed with the fate of of their experiment and ever wary of anything that might dampen its chances of success. Their eventual disillusionment with America’s constitutional order was especially profound precisely because of the transcendent importance that they attached to it. This disillusionment eventually ran so deep that their complaints and laments can seem overwrought—even hysterical—to modern readers.

For George Washington, it was the fear of parties and of divided government. Over and over again, Washington warned, a republic (res publica; common good or good thing) cannot remain if its rulers divide into Manichaean fashion. For Alexander Hamilton, it was the worry that the government lacked the energy to maintain its authority. For John Adams, the American public simply lacked virtue, the most necessary component of a successful republic. For Thomas Jefferson, it was the horrific issue of slavery that would tear the union apart.

Of the truly greats among the founders, only James Madison kept the faith.

Though excellent and thoroughly captivating, Fears of a Setting Sun is far from perfect. First, Rasmussen is too hard on Hamilton and too soft on Adams. Indeed, though often veiled in humor, the author too often expresses his likes and dislikes about his subjects’ personalities. It’s one thing to focus on quirks, it’s a different thing to mock them for the same quirks. The founding fathers were, obviously, exceptional human beings, but they were definitely human beings, possessed of both good and ill traits.

Second and far more critically, Rasmussen fails to define either a republic or a democracy, and, even worse, he often conflates the two terms. The founders, though, knew very well that a democracy must be a part of the republic, but also that it should not necessarily be the predominant part of the republic. The best republic balances monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy, letting one play off and against the others. Too frequently, the author interprets an attack on democracy as an attack on the republic.

Third, and related to the second problem, he—as author—never really engages in republican theory. He somewhat allows his subjects to explain republicanism, but Rasmussen himself fail to do so. Given how much history the founders understood, how often they chose Roman republican terms and architecture and other ancient trappings, and how classically educated most of them were, this failure on the author’s part is a significant disappointment in and of the book for me.

Fourth, his conclusion feels empty, hollow, and merely tacked on, especially after how fetching the rest of the book is. I’m guessing that some editor or some anonymous reader/reviewer somewhere made Rasmussen write a conclusion befitting the generic image of a best-selling book. Sadly, the final paragraphs of the book only serve to create some truly unnecessary and unwanted confusion to the book.

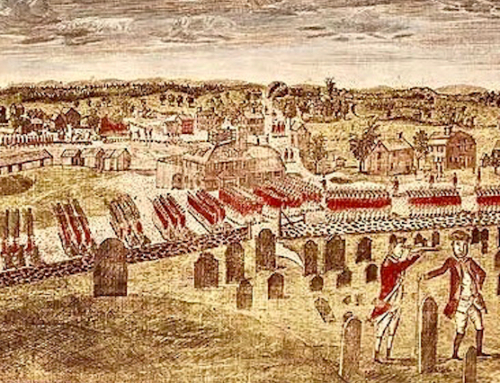

If this is indeed the lesson that we draw from the founders’ disillusionment, then we must conclude that the sun that Franklin observed on the back of Washington’s chair in Independence Hall [during the Constitutional Convention] was neither simply rising nor simply setting, but rather beckoning the nation onward toward the horizon on a never-ending quest to perpetuate and improve the founders’ creation.

What??? I’ve read this paragraph multiple times now, and I still have no idea what it means. As I wrote in the margins, “Go West, young man.” In other words, if I’m interpreting this correctly at all Rasmussen’s bizarre conclusion sounds like a rabid neoconservative and progressive pipe dream to remake the world in our image. The author and publisher would have done better to have left out the entire epilogue. Sadly, it mars an otherwise extraordinary book.

I’ve gone on way too long about the book’s faults. Every book—of every kind, of every genre, from every publisher—has such faults. But, despite what I just wrote critically above, Fears of a Setting Sun is an excellent one. The research is impeccable, the writing is nearly flawless (too many split infinitives—and here I am being critical again. . .), and the stories moving and engaging. Indeed, almost everything I wrote critically above could be corrected with just one more revision and proofreading of the book. Let’s hope Princeton knows what a treasure it has with this book and allows Rasmussen to make the book, in the language of the founders, “more perfect.”

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

So if republics fail, what is to become of us here in the USA?

Hopefully, the Republic soon ends and we get a Monarchy. I’ve seen enough of Republicanism over the last two centuries.

And why might you believe that the end of a republic results in the rise of a monarchy? Is there ever in history such an occurrence?

Didn’t Jefferson and his followers also believe republics should be small? If I am not mistaken, Jefferson also anticipated that with westward expansion, the territory west of the original states would eventually divide into smaller republics. Perhaps there is not enough republican virtue left in any region of the country today to perpetuate liberty much longer, but it seems to me that any hope for enduring republicanism probably lies in some sort of decentralization, even a division of the fifty states into smaller republics.