George Orwell was initially tempted to dismiss Charles Dickens because he seemed to have “no political program” to offer. But soon Orwell recognized this presumed defect to be a virtue and decided that Dickens was a moralist, not a revolutionary.

Having recently celebrated the anniversary of our revolution of 1776, let’s remember the kind of revolution that it was—and wasn’t. In doing so, the thoughts of two Englishmen could help direct our own thinking. Both were angry, very, very angry—and legitimately so. These well-known Englishmen were Charles Dickens and George Orwell. The anger of each was not unrelated to the anger of some of the American left today. Dickens was angered by the impact of the industrial revolution on his country and on himself. Orwell was angry at the entire capitalist system, as well as its British imperial offshoots.

Having recently celebrated the anniversary of our revolution of 1776, let’s remember the kind of revolution that it was—and wasn’t. In doing so, the thoughts of two Englishmen could help direct our own thinking. Both were angry, very, very angry—and legitimately so. These well-known Englishmen were Charles Dickens and George Orwell. The anger of each was not unrelated to the anger of some of the American left today. Dickens was angered by the impact of the industrial revolution on his country and on himself. Orwell was angry at the entire capitalist system, as well as its British imperial offshoots.

Today both left and right try to claim Orwell, who died in 1950, a confirmed opponent of Stalin and Stalinism. However, there is no doubt that he regarded himself as a man of the left. During World War II he called himself a “left-wing patriot.” And during the early stages of the Cold War he was by his own definition both a “democratic socialist” and an anti-communist.

Many on the left today could turn to Dickens or Orwell and find much with which to agree—especially when it comes to assessing what has or has not gone wrong in modern Western society… and why. But what to do in response? Ah, that is the question.

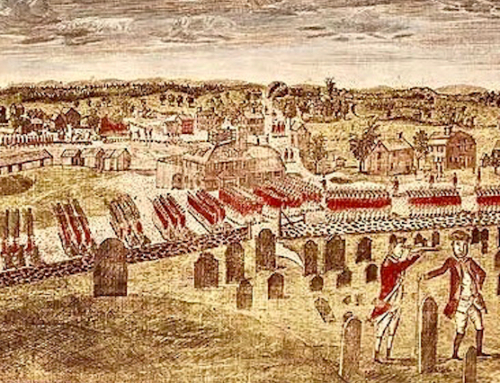

Many on the left like to compare the recent violence in our cities to violence on the road to 1776. The Stamp Act riots usually stand as Exhibit A. Violence then and violence now: It’s all the same, because it’s all directed at the same goal. Or is it?

Last summer an Antifa leader in Portland was quoted as saying that this is our moment to “fix everything.” Dickens and Orwell would have shuddered upon reading such a line.

During World War II Orwell wrote a lengthy and largely celebratory essay on Dickens. The heart of it concerned Dickens’ thoughts on social change. The original American revolution of 1776 (and the “fix everything” French revolution of 1789) might well have been hovering in the background, but neither was ever mentioned.

The ever-angry Dickens saw two possible paths for a society “beset by social inequalities,” as Orwell put it. One was that of the revolutionary. The other was that of the moralist.

Orwell was initially tempted to dismiss Dickens, because he seemed to have “no political program” to offer. But before he was finished, that presumed “defect” turned out to be a “virtue.” Dickens, Orwell decided, was a moralist, and not a revolutionary.

As such, Charles Dickens was convinced that the world will change only when people first have a “change of heart.” In the end the questions are these: Do you work on changing the system by attempting to do the impossible; i.e., change human nature? Or do you recognize that only when people have a change of heart will society improve?

It was rightly clear to Orwell that Dickens was forever holding out for the latter. Why? Because he decided that Dickens intuitively understood something that would become all too obvious in the 20th century; namely, that the revolutionary fix-everything approach “always results in a new abuse of power.”

As Orwell the anti-communist knew full well, there is “always a new tyrant waiting to take over from the old tyrant.” In fact, the new tyrant is likely to be even more tyrannical than the predecessor. Tsar Nicholas II, meet Lenin. Such a result is especially inevitable if the original motivation of the tyrant-in-training is to overhaul the entire society.

Strictly speaking, the American rebels of 1776 were neither hardcore revolutionaries nor Dickensian moralists. If anything, they were conservative rebels and hopeful moralists. Their immediate goal was to fix something, but far from everything. Their long term hope was to create a country filled with those who had had or could have a change of heart.

By cutting ties with England, the American rebels had addressed the most immediate problem that needed fixing. That act alone preserved liberties that they had but feared they were losing; hence the conservative nature of this “revolution.” The small step they took to “fix something” proved to be a giant step for all for generations to come.

Clearly, theirs was not simply a moral revolution, but many of the leading rebels were quite aware that their new republic could only be maintained by a moral people. John Adams was chief among them. Post-1776 America could only succeed if it was a nation of laws. Morality had to undergird those laws. And religion, in turn, had to undergird morality.

If there was no call to “fix everything,” there was also no call for everyone to have an immediate change of heart. Most importantly, there was no impetus to trade one tyrant for another. But the stage was set to build a country where ongoing changes of heart could, and in many case would, bring about the decent society that Adams, as well as Dickens and Orwell, hoped to see.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image combines an image of George Orwell and an image of Charles Dickens, both of which are in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Therein lies the rub. How can you change a heart when the Bible tells us that the heart is “desperately wicked”. We are seeing, right now, in South Africa and before in the US, what happens when those desperately wicked hearts have no superior force to fear. The result is total anarchy. In SA even some police have joined in the looting.

Matt 21 spells out the coming storm, let no man be deceived. The only rescue is faith in Christ,

Fair enough, not to mention darn right. Orwell was not a believer, but he was quite worried that the loss of the faith in the west was likely to doom the west.

Having written a good deal about both George Orwell and Charles Dickens, I was delighted to see this fresh perspective by M. Chalberg. My congratulations, Sincerely John Rodden