We Americans must ask: Is the republic alive? Should we despair? Are things any better in A.D. 2022 than they were for Rome in 43 B.C.?

It’s been a rambunctious (or insert the descriptive of your choice) year and a half. We’ve endured—sometimes nobly and sometimes sordidly—COVID; lock downs; race riots; the tearing down of public statues; a tumultuous election; the loss of Afghanistan; twitter, facebook, and other media horrors; a president who seems to live on a different planet; a Speaker of the House who seems to live in her ice cream freezer; and the Yankees losing to the Red Sox.

It’s been a rambunctious (or insert the descriptive of your choice) year and a half. We’ve endured—sometimes nobly and sometimes sordidly—COVID; lock downs; race riots; the tearing down of public statues; a tumultuous election; the loss of Afghanistan; twitter, facebook, and other media horrors; a president who seems to live on a different planet; a Speaker of the House who seems to live in her ice cream freezer; and the Yankees losing to the Red Sox.

We have become—to a large extent (so many extents, already)—Manicheans, religious and theological parties who divide into twos and yell at one another. Yet, without even the dignity of a Mani, we think there is the good god, and we think there is the evil god. One party screams for blood; the other for flesh. Each devours, and the middle ground is rendered obsolete.

In our division and our rage, I must ask, have we lost our sense of Americanness, our pride in our republic, our dignity in the face of the world, our very decorum as a people? Can we—even if we were so inclined—reclaim our nobility? To come to the fine point, what exactly are our Americans Ideals and our American Realities? Can one inform the other? Can one cancel out the other? Can one redeem the other?

At the moment, we seem to be the laughingstock of the world, especially after our retreat from Kabul. Imagine what Taipei or Tokyo or Seoul must be thinking right now.

It wasn’t always so. Once, we dared to be great. Yes, this is worth repeating. We once dared to be great. Before progressivism, before New Dealism, before Great Societism, before Nixon, Watergate, and Saigon, we dared to be great. After all, we were a republic—the first such republic since Cicero’s head and hands were mounted on the rostrum in front of the Roman Senate.

In his first inaugural, George Washington—the American Achilles, the American Aeneas, the American Cincinnatus—spoke beautifully about our destiny:

“I dwell on this prospect with every satisfaction which an ardent love for my Country can inspire: since there is no truth more thoroughly established, than that there exists in the economy and course of nature, an indissoluble union between virtue and happiness, between duty and advantage, between the genuine maxims of an honest and magnanimous policy, and the solid rewards of public prosperity and felicity: Since we ought to be no less persuaded that the propitious smiles of Heaven, can never be expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules of order and right, which Heaven itself has ordained: And since the preservation of the sacred fire of liberty, and the destiny of the Republican model of Government, are justly considered as deeply, perhaps as finally staked, on the experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people.”

We were meant to be extraordinary.

As with all things republican, though, we would have to endure the Polybian cycles of birth, middle age, and death. No 1,000 year reich would be America. We were organic, imitating—through the natural law—the best of life and death. As a republic, we would accept the three parts of the soul (the head—the executive; the heart—the aristocracy; the stomach—the democracy), and we could acknowledge that no true republic lasts forever.

For how long, then? A generation? Two generations? Three? Twenty? In her magisterial three volume history of the American Revolution, Mercy Otis Warren challenged our very sense of self:

“Though the name of liberty delights the ear, and tickles the fond pride of man, it is a jewel much oftener the play-thing of his imagination, than a possession of real stability: it may be acquired to-day in all the triumph of independent feelings, but perhaps to-morrow the world may be convinced, that mankind know not how to make a proper use of the prize, generally bartered in a short time, as a useless bauble, to the first officious master that will take the burden from the mind, by laying another on the shoulders of ten-fold weight.”

And,

“If this should ever become the deplorable situation of the United States, let some unborn historian in a far distant day, detail the lapse, and hold up the contrast between a simple, virtuous, and free people, and a degenerate, servile race of beings, corrupted by wealth, effeminated by luxury, impoverished by licentiousness, and become the automatons of intoxicated ambition.”

Mercy, oh, Mercy. In this, as in so much, you emulate Livy.

To the following considerations, I wish every one seriously and earnestly to attend; by what kind of men, and by what sort of conduct, in peace and war, the empire has been both acquired and extended: then, as discipline gradually declined, let him follow in his thoughts the structure of ancient morals, at first, as it were, leaning aside, then sinking farther and farther, then beginning to fall precipitate, until he arrives at the present times, when our vices have attained to such a height of enormity, that we can no longer endure either the burden of them, or the sharpness of the necessary remedies.

So, did the American republic fall as the Roman republic once fell? And, if so, when? Can she be revived?

In its death throes, Cicero reminded us that Rome had once been great, but she had lost the men to defend her:

“Thus, before our own time, the customs of our ancestors produced excellent men, and eminent men preserved our ancient customs and the institutions of their forefathers. But, though the republic, when it came to us, was like a beautiful painting, whose colours, however, were already fading with age, our own time not only has neglected to freshen it by renewing the original colours, but has not even taken the trouble to preserve its configuration and, so to speak, its general outlines. For what is now left of the ‘ancient customs’ on which he said ‘the commonwealth of Rome’ was ‘founded firm.’? They have been, as we see, so completely buried in oblivion that they are not only no longer practiced, but are already unknown. And what shall I say of the men? For the loss of our customs is due to our lack of men, and for this great evil we must not only give an account, but must even defend ourselves in every way possible, as if we were accused of capital crime. For it through our own faults, not by any accident, that we retain only the form of the commonwealth, but have long since lost its substance.”

So, again, we Americans must ask: Is the republic alive? Should we despair? Are things any better in A.D. 2021 than they were for Rome in 43 B.C.?

The republic has been declared dead before. Once, there was even a war that raged for four years, and many—especially abroad—hoped that the republic had met her match. But, virtue arose, and it struck with purpose.

General Joshua Chamberlain of Bowdoin, an academic classicist and rhetorician, witnessing the surrender ceremonies on April 12, 1865, stated it best:

Honor answering honor. . . . [as men] of near blood born, made nearer by blood shed. . . . On our part not a sound or a trumpet more, nor roll of drum; nor a cheer, nor word nor whisper of vain-glory, nor motion of man standing again at the order, but an awed stillness rather, and breath-holding, as if it were the passing of the dead. . . . Brave men may become good friends.[*]

A little over a century later—after the previously mentioned Nixon, Watergate, and Saigon debacles arose a warrior-president, the republic personified by a man, the fortieth president of the United States. Nearly forty years ago, he said to the graduating class of the University of Notre Dame:

The years ahead are great ones for this country, for the cause of freedom and the spread of civilization. The West won’t contain communism, it will transcend communism. It won’t bother to denounce it, it will dismiss it as some bizarre chapter in human history whose last pages are even now being written.

William Faulkner, at a Nobel Prize ceremony some time back, said man “would not only [merely] endure: he will prevail” against the modern world because he will return to “the old verities and truths of the heart.” And then Faulkner said of man, “He is immortal because he alone among creatures . . . has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance.”

One can’t say those words — compassion, sacrifice, and endurance — without thinking of the irony that one who so exemplifies them, Pope John Paul II, a man of peace and goodness, an inspiration to the world, would be struck by a bullet from a man towards whom he could only feel compassion and love. It was Pope John Paul II who warned in last year’s encyclical on mercy and justice against certain economic theories that use the rhetoric of class struggle to justify injustice. He said, “In the name of an alleged justice the neighbor is sometimes destroyed, killed, deprived of liberty or stripped of fundamental human rights.”

For the West, for America, the time has come to dare to show to the world that our civilized ideas, our traditions, our values, are not — like the ideology and war machine of totalitarian societies — just a facade of strength. It is time for the world to know our intellectual and spiritual values are rooted in the source of all strength, a belief in a Supreme Being, and a law higher than our own.

When it’s written, history of our time won’t dwell long on the hardships of the recent past. But history will ask — and our answer determine the fate of freedom for a thousand years — Did a nation borne of hope lose hope? Did a people forged by courage find courage wanting? Did a generation steeled by hard war and a harsh peace forsake honor at the moment of great climactic struggle for the human spirit?

Frankly, the struggle, as President Reagan understood, never really ends. When it comes down to it, I’m on the side of hope—regarding our American ideals and our American realities. To be clear, American has proven her endurance repeatedly. If we can survive Civil Wars, world wars, and Watergate, we can certainly survive COVID, the fall of Afghanistan, and the Manichaenism of social media. Let us be the sacred fire of republican liberty.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

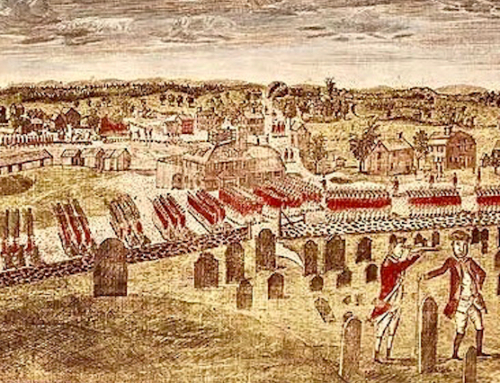

The featured image is courtesy of Pixabay.

[*]Quoted in Mark Nesbitt, ed., Through Blood and Fire: Selected Civil War Papers of Major General Joshua Chamberlain (Mechanicsburg, Penn.: Stackpole Books, 1996), 175-6.

It’s been dead for quite some time. We’re merely at the point of a near-plurality of the population beginning to realize this undeniable reality.

In his introduction to Social Change and History, Robert A. Nisbet begins with the thought provoking statement, “No one has ever seen a civilization die, and it is unimaginable, short of cosmic disaster or thermonuclear holocaust, that anyone ever will.” You know you are reading one of the great—perhaps the greatest—sociologist and a learned historian so you cannot take this as lightly as you might a quip by Howard Zinn or Jered Diamond. You must confront exactly what he is saying, and because you know he is trying to provoke, as any good teacher might, what he is saying must be true.

I believe that the Republic is dead. The facts say this, without metaphor or reiteration to an audience aware of recent history. But perhaps it was necessary for the Republic to die in order for it to live again. Re-reading his fantastic essay on metaphor, Nesbit goes a long way to making the possibility probable. It may be a little uncomfortable for those of us on the cusp of this particular moment to accept the death of our culture, but we might, as much as we are able, make the most of it. After all, we are here to see it! The death of one civilization and the birth of another. Given our technology, we had better make the new one good.

Two social-political questions are in order:

Do most Americans look at The Other Party as the Loyal Opposition, or as a vile scourge to be eliminated from public life?

Do most Americans observe the Rule of Law, even when it inconveniences their most fervent beliefs?

There is a third question, of a theological nature:

Do most Americans believe this life is all there is?

For over 200 years, though Expansion, Civil War, more Expansion, Great War, Depression, and World War, the answers have been affirmative.

If they are now negative, Conservatism has failed its mission, for there is little left to conserve, and we are in the position of that literate Roman who stands at the gate to his home, great-grandfather’s gladus in hand, awaiting the arrival of the Barbarians and knowing aforetime the final result.

Well this Manny (spelled “-ny” and not “i” though I get that misspelling sometimes) doesn’t think the Republic is dead but it’s really no longer the shining city on the hill. Something has seriously degenerated in this country and while it’s been happening for a while (since the sixties?) I can’t help but feel things took a leap during the Obama years. This became a center-left country. When the country goes along with the irrationality of gay marriage, you know the culture of the country has changed.

Of course the “death” being discussed here goes far beyond the American Republic and embraces Western civilization and culture as a whole. The reasons for it have been discussed endlessly by the finest conservative minds, including many essays found in this journal. We are going to have to resign ourselves to the fact that all earthly things come to an end, including civilization and the world itself. All that is left to do is to pray God for deliverance, while continuing to live virtuous lives dedicated to goodness, truth, and beauty.

Robinson Jeffers wrote his poem Shine Perishing Republic in the 1920’s. Paul Craig Roberts just the other day wrote his commentary on the death of a nation. All mortal things do die. The question is do the mortals comprising the nation have moral character and by what way have they shown it to be true to the values held precious? “It is indeed difficult to imagine how men who have entirely renounced the habit of managing their own affairs could be successful in choosing those who ought to lead them. It is impossible to believe that a liberal, energetic, and wise government can ever emerge from the ballots of a nation of servants.”

― Alexis de Tocqueville

Thank you for this very insightful reflection. My prayer is that many will realize what they are giving up by being complacent. This is not the time to think things will get better by just going along to get along. Our Country was once seen by the world as great; and I would very much like to see that again before the Lord calls me home, as I am 73 years old.

The words – “For the West, for America, the time has come to dare to show to the world that our civilized ideas, our traditions, our values, are not — like the ideology and war machine of totalitarian societies — just a facade of strength. It is time for the world to know our intellectual and spiritual values are rooted in the source of all strength, a belief in a Supreme Being, and a law higher than our own”. resonate deeply with me.

I was born in Eastern Europe a couple of years after WWII. After fleeing to the U.S. from socialism at the age of twenty-five, I would have never thought that I would encounter the same mentality, ideology, and propaganda here by the time I retire. Arrogant favoritism instead of merit-based achievement; political correctness instead of freedom of opinion; indoctrination and “influencing” instead of freedom of thought in education. Did I get the wrong map?

It is not you, sir, who received the wrong map! We have not yet arrived at our final destination.

Many have chosen to go-to-ground or check out rather than have to listen to the constant hyper politicization of the national narrative. Apathy and over politicization make it seem as though the Republic is dead. And as well the progressive claim that democracy is in its last throes. But most of this impression is the result of the nihilism and depression of many of in the younger generations who have been subjected to the American education system over the past 50 yeas..

I believe that much of this negativism has resulted from the secularization of the American education system which has not only been radicalized but as well has filled young minds with shame and anger about the American founding.

At the core the larger issue is the loss of spirituality in America.

We need a new affordable education platform to connect the rising generations with a reminder of the true principles and mission of America, the objective of which is to energize and motivate the younger generations to join a renewal.

Of course this renewal will have to be undergirded by an understanding of the connection between a belief in God and the existence of a self-governing representative republic which is based upon life,liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

My cohorts and I are in the process of designing a program for the family which encompasses these concepts.

The consistency of cycles of decline as revealed by JD Unwin in the early-mid 20th century forecast that the republic’s time is up.

The republic may be dead, but its ideas and ideals are not.shall we fall completely, the phoenix that will rise will be even more glorious.