Susan Treacy’s “The Music of Christendom” serves as a useful introduction to whet one’s appetite, but it could have been considerably more fleshed out. Ultimately this book is a primer, something to spark interest in the rich world of classical music in a primarily religious audience.

The Music of Christendom, by Susan Treacy (Ignatius Press, 2021, 235 pages)

The connection between music and religion is generally known and acknowledged. The praise and worship of God or the gods was a major impetus of music from earliest times. And it would be myopic not to see the fundamental role that religion has played in our Western heritage of serious, artistic (“classical”) music.

The connection between music and religion is generally known and acknowledged. The praise and worship of God or the gods was a major impetus of music from earliest times. And it would be myopic not to see the fundamental role that religion has played in our Western heritage of serious, artistic (“classical”) music.

Susan Treacy is a professor and musicological scholar who concentrates on sacred music and Gregorian chant. Yet her new book The Music of Christendom, published by the leading U.S. Catholic publisher Ignatius Press, is not a history of sacred music. Many of the works discussed herein are wholly secular. Nor is it a book about the religious beliefs or spiritual lives of the great composers. Treacy says not a word about the religious views of Mozart, Beethoven, or Verdi, even though much could be said. The title of her chapter on Haydn is not, say, “Haydn and the Smiling God” (which would fit Haydn’s spiritual outlook) but “Joseph Haydn and the Princes Esterházy,” referring to the composer’s aristocratic patron. Much less is this small volume a comprehensive history of classical music.

To understand exactly what sort of book this is, we must delve a little deeper. The jacket blurb acknowledges that the history of music is little known to the general public and presents the book as an ideal music history primer for Catholics, one that explains “how music shape[d] our civilization, and how…music itself [was] shaped by the Catholic Church.” Treacy shows her strong background in early and sacred music in the chapters about Gregorian chant, the Middle Ages and the Renaissance—after some preliminaries on “Musical Wisdom of the Ancient Greeks.” Treacy states that although “the claim that Gregorian chant is the foundation of all Western music may seem preposterous,” it is nonetheless demonstrable. (In fact, there is nothing preposterous-seeming about this claim; I would call it historical common sense.)

Treacy proceeds to a discussion of Gregorian chant, yet this tends to get bogged down in technicalities without ever reaching chant’s essence: “an unsurpassed treasure of purely melodic music” (Harvard Dictionary of Music) and “one of the most ancient bodies of song still in use anywhere” (Donald J. Grout, A History of Western Music). Incredibly, no mention is made of Pope St. Gregory, the man supposed to be responsible for Gregorian chant. Conversely, at other times Treacy allows the sonorous essence of the music she is discussing to get swamped in historical detail or verbal-poetic issues. For example, she recounts the career of the medieval composer Guillaume de Machaut yet tells us nothing about what his music sounds like.

Yet there is valuable material here. Chapters on the medieval mystic and composer Hildegard of Bingen, on the beginnings of polyphony (combining more than one melodic line simultaneously—a true breakthrough in the history of music), and on Franco-Flemish and English music of the Renaissance are all aptly chosen. They certainly go to painting a picture of music in the Ages of Faith and will be a corrective to those whose knowledge of musical repertoire is limited to Bach-and-after. The reader will be introduced to a mostly unfamiliar body of music and to the historical context that gave it birth.

The book then settles into a series of snapshots of subsequent, and to most people more familiar, Western musical history: Monteverdi’s invention of drama-in-music; Bach’s St. Matthew Passion (in some ways the result of combining operatic drama with sacred history); Handel’s Messiah; Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro; the aesthetics of musical Romanticism; Liszt and Wagner (Parsifal is singled out for special treatment); and so on. Treacy gives attention to a group of French 20th-century composers who were believing Catholics: Duruflé, Poulenc, and Messiaen. And she takes us right up to the 21st century with a “spiritual” and “spiritual minimalist” group of composers including Pärt, Gorecki, Taverner, and MacMillan.

Throughout, Treacy emphasizes music with words rather than “abstract” instrumental music—a wise choice, as beginning listeners can relate better and make spiritual connections more easily to music with extra-musical connections. Understandably given the scope of the book, Treacy has been highly selective in her choices of what composers and works to cover. But there is one surprising omission: César Franck. This highly devout and mystical Catholic should surely have been a prime candidate for inclusion.

The book is called The Music of Christendom, not The Music of Catholicism. And there’s an important point. Those not of a Catholic background are intensely aware of the Catholic nature of much Western art and music. Likewise, Catholics will need to take into consideration artistic expressions of the Christian faith that come from outside the Catholic fold, such as the poetry of Milton or the music of Bach. Treacy does not scant religious music from the Protestant world, as seen in her chapters on the St. Matthew Passion and Messiah. The post-Reformation English composers Tallis and Byrd straddled, sometimes perilously, the worlds and liturgies of Anglicanism and Catholicism. With the arrival of Russia on the musical scene in the 19th century we have a new phenomenon: composers who were formed by the traditions of Eastern Orthodoxy; hence Treacy offers for review some religious works of Rachmaninoff and Stravinsky. All of this goes to building a picture of music in Christendom broadly conceived.

The book is called The Music of Christendom, not The Music of Catholicism. And there’s an important point. Those not of a Catholic background are intensely aware of the Catholic nature of much Western art and music. Likewise, Catholics will need to take into consideration artistic expressions of the Christian faith that come from outside the Catholic fold, such as the poetry of Milton or the music of Bach. Treacy does not scant religious music from the Protestant world, as seen in her chapters on the St. Matthew Passion and Messiah. The post-Reformation English composers Tallis and Byrd straddled, sometimes perilously, the worlds and liturgies of Anglicanism and Catholicism. With the arrival of Russia on the musical scene in the 19th century we have a new phenomenon: composers who were formed by the traditions of Eastern Orthodoxy; hence Treacy offers for review some religious works of Rachmaninoff and Stravinsky. All of this goes to building a picture of music in Christendom broadly conceived.

The implicit thesis of The Music of Christendom seems to be something as follows. Western civilization is built on an enlightened Greco-Roman base and infused with Christianity. One of the artistic expressions of our civilization, classical music, was given its initial impetus by the Christian church, and many works of classical music carry a Christian ethos. More broadly, this entire tradition can be considered “the music of Christendom” insofar it is part of the Christian civilization that gave it birth.

The serious music of the West, no less than its literature or philosophy, has been infused with transcendent spiritual and moral values. This is true whether the music in question is religious or secular, a Mass or a symphony. Although one can detect a pattern in Western musical history in which music gradually moved out of the church and into secular spaces, and sacred music became less central to music as a whole, it’s equally true that sacred music survived quite well and that ostensibly “secular” genres became imbued with spiritual purpose (see Bruckner’s and Mahler’s symphonies).

The Music of Christendom serves as a useful introduction to whet one’s appetite, but it could have been considerably more fleshed out. There is no index or glossary, so when Treacy drops such terms as serialism without ever explaining what they mean, the reader will be helpless. Moreover, the selective approach to the composers and works discussed could have been supplemented by suggestions for further composers, readings, and especially recordings. And in addition to the history, it would have been good to have a bit more philosophical definition: What is it precisely that makes music sacred or spiritual? Yet ultimately this book is a primer, something to spark interest in the rich world of classical music in a primarily religious audience. If it accomplishes this, it will have accomplished a good work.

This essay was first published here in January 2022.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

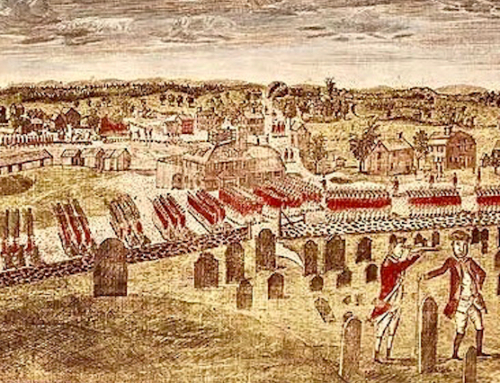

The featured image is “Saint Cecilia” (1895) by John William Waterhouse, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Thank you

It was a friend who gave me the conclusion of Newton’s Pythagorean color theory when he said that the five colors between the pentatonic scale from Cello and from Violin CGADE simply become the black keys of the piano EbF#AbBbC# which are expanded to the seven colors between the diatonic scale with F and B such that Newton achieved seven colors and these are according to the circle of quints the sensory colors BF#C#AbEbBbF which follows indigo yellow violet green red blue orange with almost complementary neighboring colors however complementary colors as far as orange is concerned indigo because FB is the wolf quint so the sense colors are found according to the circle of quints either pentatonic with five sensory colors or possibly diatonic with seven but six colors seems false since three additive basic colors red green blue EG#C and three subtractive basic colors DF#Bb magenta yellow cyan contain complementary wolf quintes EBb G#D CF# confer false twelve-tone music so five or seven sensory colors red (orange) yellow green blue (indigo) violet in Noah’s celestial bow according to folk traditions and this disagreement between five and seven colors respectively is not resolved with the help of six colors confer the circle of quints so thanks be to God and to Jesus and to the Holy Bible for Christian music