I’m fascinated by time—its past, its present, its future, its moments, its transcendences. Time, as we’ve all experienced, moves quickly at points, and agonizingly slow at other points. There is something quite mystical about the nature of time and something truly mystical in the relationship of time to eternity.

A few months ago, the history student honorary at Hillsdale College asked me (along with two other faculty members) to speak on the question, why study history. Given that, by choice, I am a professional historian, I should’ve been able to come up with some great (well, at least in my head, great) ideas as to the meaning of history, the philosophy of history, etc. Instead, somewhat to my own surprise, my answers to the question turned out to be deeply personal.

A few months ago, the history student honorary at Hillsdale College asked me (along with two other faculty members) to speak on the question, why study history. Given that, by choice, I am a professional historian, I should’ve been able to come up with some great (well, at least in my head, great) ideas as to the meaning of history, the philosophy of history, etc. Instead, somewhat to my own surprise, my answers to the question turned out to be deeply personal.

As I entered college back in the fall of 1986, I was obsessed with majoring in economics and with going into politics as a career. And, I do mean obsessed. Much of this desire had come from my four years in high school debate and forensics. For a variety of reasons, however, I found neither economics nor politics (in the practical sense; not in the philosophical sense) to my liking in college. I took one economics (for liberal-arts majors) course my first semester, and I enjoyed it very much, but I realized I wouldn’t do well with the technical side of the major. I desperately wanted to write essays like Milton Friedman, but I didn’t want to do the brilliant math behind those essays. And, as much as I had dreamed of being an orator in the U.S. Senate (yes, I had big dreams), I really didn’t possess the kind of personality—shaking hands, making deals—that such a career would demand.

Instead, that first semester of college, I immediately fell in love with my Western civilization class, and especially my professor, Jonathan Boulton, and the class’s T.A., Bruce Smith (who remains a very close friend to this day). Both professor and T.A. were incredibly witty and knowledgeable. Not only did they encourage me to write well and think well, but they further convinced me that history was the ultimate liberal art (even if not one of the seven). That is, if I wanted to employ economics, I could do so within a history major. If I wanted to study literature, I could do so within a history major. The same was true with politics, philosophy, and, well, you name it. As the slogan of the day went, “History is everything.” History was, at least in my undergraduate years, still the least infected with ideologies and theories. To be sure, I found all of this attractive. As it turned out, I came to cherish my history major at Notre Dame—not just classes with Professor Boulton and Bruce Smith, but also taking classes with and working with Walter Nugent, Father Marvin O’Connell, and Father Bill Miscamble. I can’t pass beyond Notre Dame without also mentioning my beloved American Studies professor and mentor, Barbara Allen, an incredible and joyful scholar, who made me fall in love with Willa Cather. My graduate-school professors—especially Anne Butler, Bernard Sheehan, and R. David Edmunds—continued to be grand blessings to me.

When it came time to write my senior thesis at Notre Dame (a two-semester project; with the first semester for research and the second semester for writing), I asked Walter Nugent to direct it, and he graciously did so. Again, Bruce Smith, wonderfully served as my unofficial advisor and research mentor.

This, I suppose, brings me to my second reason for being a history major. The history I wanted to study was, following the theme of his essay, not surprisingly, deeply personal. A bit of background—my biological father died in late 1967, just two months after I was born. Having never known him, I became quite taken with and turned my love (and search for identity) toward my maternal grandparents. They were the finest people in my life, and they come from a strange little segment of European life. They were known as Volga Germans—Catholics from southwestern Germany who migrated to Russia by the invitation of Catherine the Great, in 1763. They lived along the Volga River in Russia until 1876, when they migrated to six little towns in western Kansas. Tsar Alexander II had wanted to draft them into the military and force them to convert to Russian Orthodoxy. Neither appealed to my maternal ancestors, and, thus, they migrated across the Atlantic. I wrote my senior thesis tracing the history and culture of the Volga Germans.

My third (and, at least for the purposes of this essay, and final) reason for studying history is far more abstract, though it remains, too, deeply personal. I’m fascinated by time—its past, its present, its future, its moments, its transcendences. Time, as we’ve all experienced, moves quickly at points, and agonizingly slow at other points. As I age, though, I realize that for the most part, time flies! There is something quite mystical about the nature of time and, of course, something truly mystical in the relationship of time to eternity. Within time, I often wonder, how does free will work? What questions of moment are solved because of a decision, because of the unexpected eruption of a volcano, or simply because of the slipping away of time itself.

For me, no one has better captured the mysteries of time than great myth maker, J.R.R. Tolkien, especially in his scenes in Riverdell and Lothlorien in The Lord of the Rings, and the great poet and Christian Humanist, T.S. Eliot, especially in The Four Quartets.

All of these things, it seems to me, justify a major in history. To be sure, my life would’ve been radically different without such a course.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

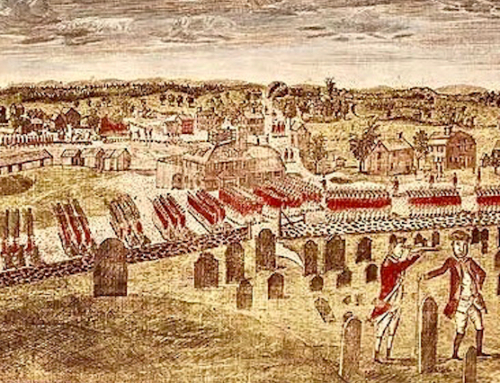

The featured image is courtesy of Pixabay.

Re: Your comment on time…I have often notice time slowing for Masses offered by my parish priest. His Masses always finish on time, but he never hurries. I can never drift off with his phrasing and presentation. The mind looks for patterns, but he never has developed any pattern in offering the Mass. I realized that he is deeply involved & thinking ? praying? Words and ideas stand out. After 50 years of NO Masses, I am finding everything fresh and new. Am growing so much. And all thanks to time slowing down to accommodate this Priest.

Birzer gives three reasons for studying history: it’s the “ultimate liberal art,” genealogy, and the mystery of free will in supplying pivot points in the seeming flow of human events.

There is, surely, a fourth reason. To peel off the ideological premises and deceptions of any given era like ours, versus, say, the Incarnation as the total and once-only intervention by the free will of God. Chesterton reminds us of a particular history, and more than just another narrative: “[T]he Catholic Church is the only thing that frees a man from the degrading slavery of being a child of his age.”

As a young child watching Little House on the Prairie and Black Sheep Squadron on tv, celebrating our nation’s Bicentennial, and reading/hearing stories from the Bible, the past was more real to me than the present was. I learned history through story/literature.

Thank you for sharing why you love history.

I love history too. For me time are Segments of eternity allotted to each organism. Everything is timed, the heartbeat, the rythms, flow, the seasons and our awareness that we are timed from the beginning. And within it a long history and chain of events….from “in the beginning”.

We want to understand who we are and so we search for the lives of our ancestors. Love that! I too am Eastern European from Prussia and Silesia and cut off from some of my past ancestry’s lives or history. But read up on all the upheavals.

But let time do its evolution. If it were not so our organism or mind and the history within it could never become conscious. We all be mad and to much to handle. I like to resolve my quest. Be thankful we are a link in the network of making or creating history. Spiritual, educational, relational, political or by what ever means comes naturally. My little five cents worth and grateful for my life and history…for better or worse bound to time. History will always be personal if it is to have meaning.

Lovely explanation of the love of History……..

Interesting essay. I enjoyed it! 🙂

My lifetime study of history (and I am a humble amateur, not a professional) has been a great help to me in making judgements on the accuracy of the historical pronouncements that are often made in many non-scholarly/popular publications. I have also gained a deep appreciation of the saga of those cultures and civilizations to which I have some personal connection, as well as of the story of mankind in general. From Lugalzagesi to the 117th Congress, we all part of the same epic.

History didn’t interest me much as a young man, but it sure does now, especially intellectual history.

What wonderful replies to an, as usual, enjoyable and insightful essay.

I’d like to offer my translation of your deeply personal points in an attempt to address where you initially set out to answer the question posed…

1) History is the unifying link that gives context to all other intellectual disciplines, then opening the door to the spiritual.

2) History gives one insight into their own place i the world (and in time) so that we can function with more insight, meaning, and passion.

3) History presents… aw heck… I guess I gave this one up up in numero uno.

Me too, Dr.Birzer. Looking back at my, rather limited experience of Christian men, but loving it, and thanking God for them (my history professors!) I’m hurrying to thank you all at TIC for publishing some of the best narratives ever.

Finally, I knew about the importance of the Volga Germans. But that they barged into Kansas in 1876, astonished me!? I’m thrilled to hear of them. Did Tolkien also learn of them? Now there’s a tale worth telling. Right? So, THANKS.

Wonderful! As I age history becomes ever more interesting and its study ever more necessary. And it seems much shorter and everything more recent.

Being a historian, is to practice the profession of seeking the facts and meaning of the past and recording those facts and meanings for posterity. It is a sacred undertaking. But even when following the highest standards for professionalism and honesty, the writings of historians are shadows on the cave wall. Nevertheless, “seeing” these shadows orients us to our place in cosmic time. It connects us with our humanity and reveals a bit about the nature of God. The honest historian, dedicated to factual accuracy and the truth of the past, helps keep us civilized. Sadly, the honest historian dedicated to factual accuracy and seeking a plausible truth about the past is beginning to disappear from the academy and thus from our Western Civilization. Many newly minted historians leaving the academy today are little more than postmodern propaganda artists who lie and manipulate their “history” to attain standing in today’s cult-like lost-at-sea academy. Too many, if not most 21st century historians are working fervently to deconstruct Western Civilization and lead us into an age of evil, ugliness, filth and demonic totalitarianism. Let us pray that, in the due course of time, they will be sufficiently opposed.

It is vitally important for the survival of our nation that there be historians and that those historians know and promulgate history. The facts of history and not ideology must be remembered. In one of your answers, you refer to the mystery of time. That is a important dimension of the study of history because awareness of this mystery, plus the mystery of belonging, and other mysteries allay some of the angst and rootlessness people lacking that awareness feel. In studying my family history, I have uncovered such individuals as John Books, who fought at the Lexington conflict, among others, who fought at Bunker Hill and Bennington. This knowledge provides a deep feeling of belonging in the greater scheme of things.

An excellent sonnet regarding your love of history and the mysterious ways of women and men through time. What is your evaluation of Alexander Butterfield’s “The Whig Interpretation of History”?