In very different historical circumstances, two strong-willed, athletic men with intelligence and leadership ability survived multiple dangers, but neither attributed his survival to his abilities or to sheer willpower. Instead, both men consistently and publicly credited Divine Providence. Their stories are well-known, but worth reviewing, since they serve as witnesses to us in our own challenging circumstances.

In very different historical circumstances, two strong-willed, athletic men with intelligence and leadership ability survived multiple dangers, but neither attributed his survival to his abilities or to sheer willpower. Instead, both men consistently and publicly credited Divine Providence. Their stories are well-known, but worth reviewing, since they serve as witnesses to us in our own challenging circumstances.

The first American is our celebrated George Washington. While his life is famous, we may not have considered certain incidents in the light of his spiritual life of faith. Such considerations are presented in The Spiritual Journey of George Washington (2013) by Janice T. Connell. I will here focus on some particularly striking episodes described in her book, which become significant in light of an extraordinary spiritual event that occurred in Washington’s darkest hour of the Revolutionary War.

The foundation for George Washington’s strong and personal Christian faith is revealed in an anecdote relating how his father Augustine chose to teach him about the fatherhood of God. It is told that Augustine had him plant cabbage seeds in a pattern spelling out “George,” and, after George carefully watered it for a while and his name emerged, the young George expressed amazement and asked, “How did this happen?” His father explained, “This is a great thing, an important thing, a vital thing…. I want you to understand my son that I am introducing you to your true father, the source and sustenance of all life, even yours” (p.6).

George’s mother was very devout and strict in observance of the Christian faith and taught young George the Bible from the cradle so that it became a source of strength for him in the challenges he was to face. This included hardship and suffering as well as strenuous work while growing up. When he was 11 years old, George’s father died and his mother, then a widow with six children, had to rely on her eldest son (George), who held her legal rights (p.68). The experience of these years shaped George’s physical and emotional strength as well as skills in business enterprise. When his older half-brother Lawrence, who had been a great help to him, died of tuberculosis, 20-year-old George endured another suffering and challenge in which his faith in God’s ways was tested; yet it endured.

Sent into the Ohio valley as a young officer (22 years old) to challenge the French stronghold of Fort Duquesne, George Washington was faced with a hopeless military task. Yet he learned to call on moral force as well as diplomacy in this situation. The Indian leaders of the Ohio Valley took note of the young Virginia officer, and the Indians’ “Half King” told them that he discerned in him a spiritual greatness and that he could trust him. (p.57) Particularly striking was an incident that occurred in which Washington and an aide were cutting through the woods when they were ambushed by a party of French Indians. One of the Indians, who Washington said was “not fifteen steps off,” fired directly at the Virginian’s chest, yet the bullet did no harm to him despite being discharged at such close range. The firing Indian, it is reported, fell to his knees to worship “the giant his shotgun would not kill” (quoted from Washington’s diaries of 1753 by Lonnelle Aikman in Rider with a Destiny (1983).

As a captain in the French & Indian war, Washington developed severe dysentery, as the British were attempting to liberate Fort Duquesne from the French,. Determined nevertheless to participate in the battle, he tied several pillows to his saddle to lessen his pain. During the fierce combat, his horse was shot out from under him twice but each time he found another horse and remounted with his pillows. Seated high on his pillows, he was an easy mark for the hidden riflemen.

An unseen rifleman fired at his face and pierced his hat. Two more bullets scorched through his hat…. Then hot lead pierced his uniform, but he remained untouched. Eyewitnesses were both stunned and frightened. The myth of the invincible George Washington, an American Achilles, was born during that battle (Connell, p. 61).

In a letter George wrote to his brother John in 1755, he said of the battle: “By the all powerful dispensations of Providence, I have been protected beyond all human probability or expectation, for I had four bullets through my coat and two horses shot under me, yet escaped unhurt, although death was leveling my companions on every side of me.”

The times when George seemed almost miraculously preserved from death were described in Patriot Sage (ed. Gary Gregg and Matthew Spalding:

His immunity to gunfire seemed almost supernatural…. Once he rode between two columns of his own men who were firing at one another by mistake and struck up their guns with his sword—the musket balls whizzed harmlessly by his head. Time and again during the Revolutionary War musket balls tore his clothes, knocked off his hat, and shredded his cape; horses were killed under him; but he was never touched. What mortal could refuse to entrust his life to a man whom God obviously favored?

A biography by John Alden described what happened at the Battle of Princeton during the Revolutionary War:

[Washington] preferred to risk his own life to achieve success rather than to remain safely behind his men and perhaps in consequence to receive reports of defeat. Conspicuous on a white horse, he rode forward within thirty yards of the British line, urging the men to follow him in attack. The smoke of gunfire enveloped him. His men feared that he was slain, but he was unscathed. The Patriots rallied behind him” (George Washington, A Biography, 1984).

Washington firmly believed that it was “Kind Providence” that protected and led him. In a letter to Samuel Langdon (1789), he wrote:

The man must be bad indeed who can look upon the events of the American Revolution without feeling the warmest gratitude towards the great Author of the Universe whose divine interposition was so frequently manifested on our behalf. And it is my earnest prayer that we may so conduct ourselves as to merit a continuance of those blessings with which we have hitherto been favored.

Then there is the famous Indian prophecy: In 1772, when Washington was on a business trip traveling through the Ohio valley with a group of hunters, an aged Indian chief of imposing appearance rose to his feet at the camp fire, bowed to Washington with great deference, and addressed the group with these words:

I am chief and ruler over my tribes. My influence extends to the waters of the great lakes and to the far Blue Mountains. I have traveled a long and weary path that I may see the young warrior of the great battle. It was on the day when the white man’s blood mixed with the streams of our forest, that I first beheld this chief. I called to my young men and said, mark yon tall and daring warrior? He is not of the red coat tribe—he hath an Indian’s wisdom and his warriors fight as we do—himself alone is exposed. Quick, let your aim be certain and he dies. Our rifles were leveled, rifles which, but for him, knew not how to miss—twas all in vain, a power mightier far than we shielded him from harm. He cannot die in battle. I am old and soon shall be gathered to the great council fire of my fathers in the land of shades but ere I go there is something bids me speak in the voice of prophecy. Listen! The Great Spirit protects that man, and guides his destinies—he will become the chief of nations, and a people yet unborn will hail him as the founder of a mighty empire” (George Washington, the Christian, 1919, by William J. Johnson).

These stories are important preludes to the most extraordinary experience of all. In the darkest days of discouragement at Valley Forge during the winter of 1777, Washington was deeply concerned about his men and the prospects of their desperate war for freedom. As was his habit, the commander turned to prayer for help from God. Then, alone in his quarters, he looked up to see standing across from him a beautiful lady. Her sudden appearance startled and transfixed him. As he related afterwards to Anthony Sherman and another officer, the atmosphere seemed to grow luminous, and after some time as he gazed fixedly in wonderment at the lady, he heard her address him: “Son of the Republic, look and learn,” while pointing eastward. He then was shown a vision of European countries from which a cloud moved across the Atlantic and enveloped America. He heard groans from America, but eventually the cloud moved back across the ocean. Then the lady again said, “Son of the Republic, look and learn,” and he was shown a vision of America filling up with towns and cities from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Next, in another vision, he was shown the inhabitants of America battling against each other until a bright angel with a crown bearing the word “Union” placed an American flag between the warring parties and cried, “Remember, Ye are brethren,” after which the inhabitants threw down their weapons and became friends again around the flag.

In a final vision, he was shown hordes of armed men coming across the ocean from Europe, Asia, and Africa and attacking America, devastating the whole country. But finally, a bright angel rolled back the dark cloud over America and the attacking armies, and the inhabitants of America were left victorious. The angel proclaimed in a loud voice: “While the stars remain and the heavens send down dew upon the earth, so long shall the Union last.” The lady addressed him once more, saying “Son of the Republic, what you have seen is thus: three great perils will come upon the Republic. The most fearful is the third, but the whole world united shall not prevail upon her. Let every child of the Republic learn to live for God, his land and the Union.” She then disappeared from his sight.

This is a brief summary of the visions. It is most moving to read the entire account as recounted in The National Tribune of December 1880 (available online and in the Library of Congress), and repeated in Janice Connell’s book. The Blessed Mother Mary has often appeared at times of great need and dangers. Since George Washington had a business partnership with Daniel Carroll, the brother of the Jesuit Fr. John Carroll, it is most likely that he would have shared his vision with Fr. Carroll. Then in 1792, as the first Archbishop of America, John Carroll made a solemn and official consecration of the new nation to Mary Immaculate in 1792.

Washington continued his faith in the guidance of “Kind Providence” as he served in Congress and as President of the young nation, which he believed was destined to unfold the loving plan of Kind Providence for the benefit of her people whom God loved. He was aware of the importance in the developments of world history. He had written to General Thomas Nelson in 1778 that

the Hand of providence has been so conspicuous in all this [Revolutionary War] that he must be worse than an infidel that lacks faith, and more than wicked, that has not gratitude enough to acknowledge his obligations (Connell, p. 96).

Washington consistently shared his religious convictions on the national stage, while always being respectful of different denominations and other religions. The phrase used at the conclusion of the presidential oath, “So help me God,” and the gesture of kissing the Bible were improvisations of Washington. His prayer life was private but its fruit was public. He always considered that he was a beneficiary of God’s merciful providence and a servant of His plan to accomplish justice and peace in the new nation. According to Connell, “Washington prayed often that he might adhere to God’s loving plan for his life of service to his new nation” (p.80). When retiring from his command of the Continental Army, he wrote to the governors of the 13 states, concluding with this prayer:

I now make it my earnest prayer that God would have you and the State over which you preside in His holy protection… that He would most graciously be pleased to dispose us all to do justice, to love mercy, and to demean ourselves with that Charity, humility and pacific temper of mind which were the Characteristics of the Divine Author of our blessed Religion [Judeo-Christianity], without an humble imitation of whose example in these things, we can never hope to be a happy Nation. —The Circular Address to the States, June 8, 1783

Finally, in his Farewell Address, 1796, Washington advised:

Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, Religion and morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of Patriotism who should labor to subvert these great Pillars of human happiness, these firmest props of the duties of Men and citizens. The mere Politician, equally with the pious man ought to respect & to cherish them…. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure—reason & experience both forbid us to expect that National morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.

***

Another American in a later time period faced dangers in very different circumstances. He possessed a personality and background that differed from those of George Washington, but he also had a strong Christian faith that brought him to the firm conviction that Divine Providence had directed him from the beginning. This was Walter Ciszek, born in 1904, a son of Polish immigrants living in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania. As a boy, according to his description, he was “a tough”—a bully, a leader of a gang, a street fighter, who played hooky from school and had to repeat a whole year. He was good at sports and was determined to do better at a game than anyone else. He was stubborn and liked to challenge himself to do anything that was hard to do. Out of this raw material, God in His own way formed what turned out to be an inspiring life.

When Walter was in eighth grade, he decided he wanted to become a priest. His father, a kind and thoughtful man, had been disappointed and frustrated with Walter’s behavior thus far, so he could not believe this decision was real. His mother, who was religious and had trained him in the faith and prayers since a young age, did not discourage him but told him that “if [he] wanted to be a priest, [he] had to be a good one.” Walter did go off to seminary that fall. Because he liked to be tough, he challenged himself to do everything that was hard to do. When he read the life of St. Stanislaus Kostka, he decided he wanted to become a Jesuit, even though he had serious hesitations about obedience and the long study required. After much prayer, he finally settled on this decision and completed his application. He said he then felt a great sense of deep and satisfying peace. Though not an ideal novice, and one who gave his superiors doubts about his vocation, he persisted, learned, and adjusted.

Then, as though the life of a Jesuit priest was not hard enough, Walter felt drawn to a further challenge. In 1929, Pope Pius XI sent a letter asking for seminarians who would commit to being trained for working in a mission to Russia. The Soviet persecution of religion had resulted in the arrest of all the Catholic bishops and the closing of all the seminaries, such that hundreds of parishes were without priests and it was forbidden to teach religion to children. The Holy Father was calling for especially courageous priests who would be specifically trained for this mission. Walter was immediately stirred and felt that, after a long search, here was what God was calling him to, specifically placing in him a desire for this.

Walter was allowed to go study in Rome to prepare for this mission, learning Russian and the Oriental Rite. After three years of study, he was ordained in 1937, but then was informed that it was impossible to go to Russia at that time. He was sent instead to work in an Oriental Rite parish in eastern Poland. After the Nazis attacked Poland in 1939, Russia invaded eastern Poland. His Oriental Rite parish, after multiple difficulties under Russian occupation, was ordered by the Jesuit Superior to close. Two priests who had trained with Walter in Rome for the Russian mission were sent by the Superior with the termination order. These two priests, one a Georgian and one a native Russian, who were particularly enthusiastic and determined about the mission to Russia, suggested that they join the groups of laborers who were being sent to work in Russia and look for opportunities to do pastoral work with them. This they did, and thus began a long saga of adventure and danger for Fr. Walter Ciszek, S.J., in Soviet Russia.

This adventure needs to be read in Fr. Ciszek’s own words in his autobiographical book, With God in Russia. I will here only summarize some important points and Fr. Ciszek’s reflections. His second book, He leadeth Me, describes his spiritual struggles and reflections about Divine Providence. The important goal of Fr. Ciszek’s entry into Russia was the dream of ministering to Russian communities deprived of their priests. How did this work out? What were the successes and failures? What was the “spiritual journey” for Fr. Ciszek in this antagonistic Soviet environment?

Inititally, Fr. Ciszek and Fr. Nestrov (the native Russian) were sent to work for a lumber company near the Urals. They had to be very cautious in sounding out attitudes toward religion. There was the constant fear of being discovered as priests. Propaganda speeches against religion were frequent. They found that most of the men were indifferent toward religion, which made their dream of pastoral work seem unpromising, and it was easy to become discouraged. “In times of discouragement, [Fr.] Nestrov and I consoled ourselves with thoughts of God’s Providence and His omnipotence. We placed ourselves and our future in His hands, and we went on,” Fr. Ciszek recounted (With God in Russia, p. 55). Their work had to become their prayer. Yet they eventually encountered many people who were religious at heart and who prayed in secret. Some were wishing their children could be baptized, so the two Jesuits explained to them quietly how the parents could baptize their children. They grew a little bolder in attempts to talk about religion. They made friends with the children and asked them what they had been taught about God. They found that teenagers were interested in religion, so they organized meetings with them in the forest while picking berries and mushrooms. They were able to talk to them for hours about God and man. On occasional trips into the countryside, Fr. Ciszek found peasants who talked freely about religion and who wished there were a priest for their community, but he couldn’t tell them he was a priest. However, in trips to the hospital, he would tell the patients he was a priest so that he could minister to them.

After the Germans invaded Russia in June of 1941, the Soviets arrested a number of the laborers in the camp, accusing them of being German spies, including Fr. Ciszek and Fr. Nestrov. They were all placed in crowded prison cells with appalling, degrading conditions. Now the earlier feeling of frustration was replaced with a sinking feeling of helplessness and powerlessness. Worst of all for Fr. Ciszek was the shock at experiencing the degree of disrespect and contempt for him from other prisoners when he revealed he was a priest. Soviet propaganda had taken its toll and people had accepted the lies about priests. “I was cursed at; I was shunned; I was looked down upon and despised” (He Leadeth Me, p. 45). Having grown up in a Polish Catholic environment where priests where always respected, Fr. Ciszek was bewildered and dejected at this prejudice. There was no one he could talk to, or find sympathy and understanding. He turned to God in prayer and reflected that since he was despised specifically for being one of His priests, God would comfort and console him since He Himself had been rejected by men. He then found, as he had in the past, that God’s way of consoling him was to increase his self-knowledge. The grace he received was to realize how much self-pity was mixed with his feelings of humiliation. He reminded himself that he shouldn’t be expecting that “the servant [be] greater than the master.” If he was truly following Christ, should he have expected anything different?

Another insight Fr.Ciszek was given was to remember that no situation is without purpose in God’s Providence. These people in this place and time were God’s will for him now. God expected him to act according to the grace He would provide. He would

in some small way at least touch their lives too…These men around me were suffering; they needed help. They needed someone to listen to them with sympathy…to give them courage to carry on. They needed someone who was not feeling sorry for himself but who could truly share in their sorrow…. God… was asking only that I learn to see these suffering men around me, these circumstances in the prison at Perm, as sent from his hand and ordained by his providence…. He was asking me to forget about my ‘powerlessness’ against the ‘system’ and to look instead to the immediate needs of those around me…to see that this day, like all the days of my life, came from his hands and served a purpose in his providence” (He Leadeth Me, p.49-50).

Then a new and different challenge for Fr. Ciszek transpired. He was accused of being a Vatican spy and sent to the most dreaded prison of all, Lubianka, in Moscow. Here he was in solitary confinement, and he found the lack of human contact and the oppressive silence even more dreadful than the crowded, degrading conditions in the previous Soviet prisons. In Lubianka, days stretched endlessly with no variation. He ended up spending five years in this prison. How did he survive without going stir-crazy? “When you are left alone in silence and solitary confinement with this surging sea of thoughts and memories and questionings and fears that is the human mind, you either learn to control and channel it or you can go mad,” Fr. Ciszek commented. (He Leadeth Me, p.55) The way Fr. Ciszek maintained inner control was by drawing on his Jesuit training to establish a “daily order.” This consisted of: Morning Offering upon awakening, plus an hour of meditation, then after breakfast saying the prayers of the Mass, reciting the Angelus morning, noon and night, doing an examination of conscience at noon as well as before bed at night, saying three rosaries in the afternoon (one in Polish, one in Latin, and one in Russian), and chanting hymns in Polish or Latin or English. He had his distractions, of course, especially some extreme pangs of hunger. Gradually, he learned to purify his prayer. Certainly prayer, placing himself in the presence of God, helped him through times of crisis. And with the Lord’s Prayer “Thy will be done,” there was a great strength. “I had to learn to find him in the midst of trials as well as nerve-racking silences, to discover him and find his will behind all these happenings, to see his hand in all the past experiences of my life… to ask at every moment for his constant, fatherly protection against the evils that seemed to surround me on all sides.”

There were further challenges that brought Fr. Ciszek to a deeper self-knowledge about his need for abandonment to God’s will in all circumstances. The interrogations that he had to endure brought him face to face with his own weaknesses, doubts, and self-will. He came to realize that he was relying too much on his own abilities instead of trusting God. Then after five years in Lubianka, he suddenly found himself on the way to labor camp exposed to a very different and rough world, surrounded by hardened criminals, violent and without scruple. Fr. Ciszek had to struggle to see these men and circumstances as part of God’s will for him at this time.

When he arrived at the labor camp in northern Siberia, he had one great consolation. There were other priests there, and he was able finally to function as a priest again, the priests providing each other mutual support. He could say Mass (though in secret), hear confessions, baptize, and minister to the sick and dying. He could speak about God, strengthen weak faith, and teach the truths of Christianity. Discretion was needed, of course, because priests were watched by security and harassed with interviews and intimidation. But he was greatly encouraged to find that a priest was sought out; he didn’t have to create contact. The power of the sacraments to draw people in their need was impressive and gave him great joy. Since they came for God’s grace and not for him personally, this increased his humility and his dedication to the ministry he was called to provide no matter how exhausted he was from the intense labor of the day’s work, or how risky the official surveillance was. God was at work here, not because of him but because of God’s love for these most abandoned people. Now Fr. Ciszek was able to realize how God’s Providence had led him to this work through all the earlier frustrations and purifications that he had endured. He had learned, through hard tests, important lessons about himself and about God’s ways, which prepared him to be of humble service to these needy prisoners.

For the many in the camps who did not understand religion or the priesthood, the witness of how the priests in the camp lived their faith drew their respect, and even admiration, and sometimes inquiry. Fr. Ciszek explains:

They were wise in the ways of the prison camp and prison system; they knew that priests were the object of special harassment by the officials. Yet they saw these same priests refuse to become embittered, they saw them spend themselves helping others, they saw them daily give of themselves beyond what was required without complaint, without thinking of themselves first, without regard for their own comfort or even safety. They saw them make themselves available to the sick and to the sinning, and even to those who had abused or despised them. If a priest showed concern for such people, they would say, he must believe in something that makes him human and close to God at the same time (He Leadeth Me, p.116-117).

This sometimes resulted in the great joy of helping a prisoner return to belief in God or to the practice of a religion that he had abandoned for many years.

The primary members of the labor camp “parish” were Catholics of Polish, Ukrainian, Latvian and Lithuanian descent who were delighted to have priests available to provide the sacraments. They gave witness to the other prisoners that faith provided them with a deeper dimension, giving purpose to their life and protecting them from despair in the harsh conditions of prison life. Getting together with these “parishioners” had to be done in secluded places for fear of official repression. There were clandestine Masses, baptisms, rites for the dead, and sick calls. Confessions and a word of advice or prayer might be done while walking about the camp or marching to work. A priest in these circumstances realized how impossible it was to have any significant influence on the people living in the Soviet state dominated by atheistic propaganda. His task was a simple one: to respond to what the people asked of him each day and trust God for the rest, to be another Christ in this environment, offering his labor and suffering for others, and being a mediator for the people before God. For Fr.Ciszek, after all his years of isolation and loneliness in Lubianka, it was a great joy to be able to carry out his priestly ministry in these labor camps of arctic Siberia.

One startling incident threatened to end Fr. Ciszek’ life and revealed again the intervention of God’s providence. Some of the prisoners organized a revolt to pressure for changes in the prison conditions, and Fr. Ciszek was drawn into it. As a result, a group of the prisoners, including Fr. Ciszek, were taken out of the barracks and lined up before a firing squad. When rifles were raised, cocked, and aimed at their heads, the imminence of death was paralyzing. With only a fraction of a second to spare, however, a sudden shout commanded a stop to the execution.

After fourteen years and nine months of his fifteen-year sentence, Fr. Ciszek was liberated, although with restrictions on where he could travel or work and with registration with the police required. In traveling to the nearby city of Norilsk, he was reminded of his first trip into Russia and reflected on how much he had learned, how imperfectly he had understood doing the will of God, how his painful failures had been lessons in self-knowledge and abandonment to God. The restricted freedom he now experienced was not as important as the spiritual freedom from the conviction that God was directing him along the paths of His Divine Providence. In Norilsk, he was able to work with two other priests previously freed from prison, and found they were overwhelmed with crowds of people coming to them for Mass and the sacraments. He was given his own “parish” of Poles who were housed in old camp barracks. While both he and his parishioners were under regular surveillance, the faith and courage of the people amazed him, and their persistence in practicing their faith despite the pervasive atheism of Soviet Russia. They were “a living witness in this desolate land to the power of God’s grace and the existence of his kingdom” (He Leadeth Me, p. 177). Lent and Easter became intensely busy for Fr. Ciszek, since the other two priests had left the city and the congregation had become bigger than ever. From hearing confessions all day Friday, through evening services, he worked non-stop up to and through Easter morning. But exhausted as he was, the elation of this Easter with so many eager crowds gave him a joy he said he had rarely felt. “I felt that at last in God’s own good providence, I was beginning to live my dream, of serving his flock in Russia” (Ibid., p. 179).

However, sadly, it couldn’t last. A week later, the KGB put an end to this joyful work and ordered him to leave Norilsk. Once again, he felt humiliated and resentful at the way he could be ordered around even though supposedly a free man. But this time, he was firmer in believing that this was part of God’s plan. It was natural that he would be disappointed at having to leave this particularly rewarding experience as a priest just as it seemed to be going so well. He told himself he should have confidence that God could find other ways to take care of his people. It was his task to follow where God was leading him in the events of his life. It is in such times of doubt and disappointment that one needs to persevere in trusting God and be peaceful about it.

The wonder of Divine Providence was once again revealed when Fr. Ciszek arrived in his next destination, Krasnoyarsk. While registering with the KGB, he was approached by an elderly Lithuanian, who asked him if he was Catholic and told him that he was a member of a parish on the outskirts of the city where the priest had recently died; they were looking desperately for another priest. Not having told him he was a priest out of caution, Fr. Ciszek was amazed at what God seemed to be arranging for him. He agreed to follow him and found the people had their own church and a room for a priest to live in. When he told them he was a priest, they were overjoyed. He was impressed by the strength of their faith and their boldness in petitioning the town not to confiscate their church since they now had a priest.

However, once again, his ministry with this parish was not allowed to endure. One morning at one o’clock, the secret police showed up and told him he had two days to leave the town. He ended up being sent to the southern town of Abakan, where he got lodging with a Communist party member for two years and worked in a city garage. However, here he had an opportunity to learn about daily life and family life through conversation with families and their friends. Eventually it became known that he was a priest, and he began to again be busy hearing confessions, baptizing, and counseling. He continued to be impressed by the sacrifices people made to persevere in their faith. His love for these Russian people grew deeper. “The example of such courageous Christians,” Fr. Ciszkek said, “the curiosity and questions they inspire, do not make many converts—nor did my long conversations and explanations. But they must surely prepare the ground for the seeds of faith, which God alone can plant in the hearts of men. God in the wonderful ways of his divine providence uses many means to attain his end” (p.204).

In October of 1963, Fr. Ciszek was returned to the United States in exchange for two Russian spies. When people asked him, “How did you manage to survive?”, he would reply, “Faith… sustained me in all I experienced.” The simple truth is that God has a special providence for each of us individually, he would explain. “Every moment of our life has a purpose…, every action of ours, no matter how dull or routine or trivial it may seem in itself, has a dignity and a worth beyond human understanding…. Nothing can touch us that does not come from his hand; nothing can trouble us because all things come from his hand. This is the only secret I have come to know,” Fr. Ciszek shared (p.207-208).

It is helpful to remember that this lesson was learned in the midst of the most trying of circumstances of prison life, secret police interrogations, labor camps, and the pressure of constant surveillance while striving to do the work of God in atheistic Soviet Russia. In these days of unsettling events and evil influences, it is encouraging to remember these examples of how Divine Providence can protect one even in the most difficult and dangerous circumstances.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

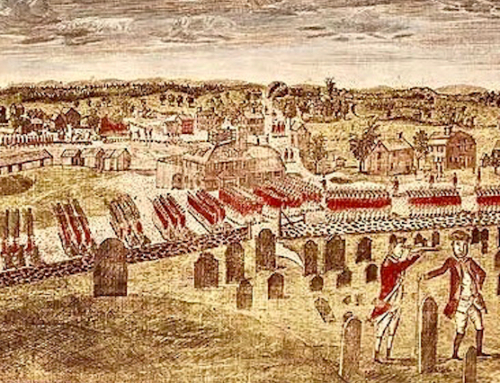

The featured image is “Passage of The Delaware” (1819) by Thomas Sully, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

I enjoyed reading of these two me under different circumstances reactng to the grace God had given to them to perform their duties for Him.

I had not heard of G. Washington’s visions before, but it is an experience many faithful people have with a life full of prayer,

My fear for America today is our leaders in Washington DC are godless men and women and we will surffer the consequences of ther lack of acknowledgement of God..

I pray for our leaders in our Government and the Catholic Church that they may govern and lead us by our Savior’s intentions.

The John R. Alden book, George Washington: A Biography, which you quote for his description of Gen. Washington at The Battle of Princeton….

Having borrowed part of this quote for a biography of my own, I am now seeking permission to use it from the publisher.

For my trouble, could you tell me on which page this quote appears? Thank you.