In classical education, we are not talking about tradition as the acquisition of monuments, but as a permanence gathered from moments of participation capable of being lived and lived again and then passed on to be taken up yet again by generations yet to come, with our own additions and our own achievements of greatness.

Each year, the evening before Wyoming Catholic College’s graduation exercises, we celebrate our senior with a formal dinner, The President’s Dinner, which includes seniors, their families and friends, as well as college faculty and staff. At this dinner, I have the opportunity to address the seniors one last time. Below, an excerpt of my comments to the Class of 2023.

Each year, the evening before Wyoming Catholic College’s graduation exercises, we celebrate our senior with a formal dinner, The President’s Dinner, which includes seniors, their families and friends, as well as college faculty and staff. At this dinner, I have the opportunity to address the seniors one last time. Below, an excerpt of my comments to the Class of 2023.

Since I became president, there have been several classes to graduate without my ever having taught a single one of them in a single class during their eight semesters here with us—and this is one of those. But I am confident that they have had a prolonged encounter with what is great and permanent and true, and I know that the weave of the education has come in its distinct way to each of them. Many experiences have been fleeting and irrecoverable—an exchange in a seminar or a late-night conversation when insights suddenly came together; a vision of the mountains at dawn in the back-country; all those small but life-changing instants of intercession or consolation or grace.

I’ve come to know the seniors in other ways, of course, such as directing two of the senior theses, one by Grace Dennett, and the other by Jacinta St. Pierre. Through Grace I got to revisit the superb, almost magical prose of the Russian novelist Vladimir Nabokov, whose imagination has a metaphorical intensity that speaks to something both tragic and transcendent. From Jacinta, I heard the cacophony of Dante’s hell and then the strains of the music that increases in complexity as we rise through Purgatorio and into the polyphonies of paradise. It was a great pleasure to me to work with them both. And of course, during these four years, my wife and I have had these students over to our house on many occasions. Many of them are good friends of our daughter Julia.

WCC often describes itself as counter-cultural. We are very different from so-called mainstream universities because of our technology policy; we are part of a small group of sister institutions in our rejection of woke ideology, including its assumptions about human nature and its agenda to destroy the traditional family. As we draw closer to the ceremony of departure that we call commencement, I am led to reflect again on the effect of all the converging disciplines and experiences on the souls of these graduates—that is, on the very form of who they are. We are realistic about contemporary culture, but also realistic about what it means to participate in the living continuance of the tradition that these seniors have experienced in these four years.

What does tradition mean in this sense? The word might suggest a museum of old ideas where each piece must be dusted off and treated with dutiful reverence; it might suggest mere repetition of past attitudes. But over a century ago, T.S. Eliot made it clear that tradition is the source of creativity and the wellspring of culture. When you give yourself to one of the great books of the tradition, it is not like entering archaeological ruins and trying to imagine what used to be there. Far from it. It is not something past, but an encounter of minds in the living moment. Reading these texts is not a glimpse of unreachable truth, but a participation in the live weaving of the image or exchange.

Patroklos has fallen, you have no armor, and so, prompted by the goddess, you stand outside the wall and the ditch that surround the Achaian ships, and Athene kindles such a great flame from your rage that it blazes up from your head into the dying day and she amplifies your shout so much that twelve Trojans die in the panic of their horses. Or you argue with Socrates just as Thrasymachus or Glaucon might do. Or you read St. Augustine: “Our hearts are restless until they rest in Thee”—the same sentence that St. Thomas Aquinas read, or Dante, or St. Therese, or John Henry Cardinal Newman, speaking of tradition. Or you hear in class one of your classmates read Lear’s speech to Cordelia:

Come, let’s away to prison.

We two alone will sing like birds i’ th’ cage.

When thou dost ask me blessing, I’ll kneel down

And ask of thee forgiveness. So we’ll live,

And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh

At gilded butterflies.

It says something about tradition that these very lines are the ones that John Milton read or John Keats or Abraham Lincoln or Winston Churchill or Pope John Paul II.

In other words, in an education like this one, we are not talking about tradition as the acquisition of monuments, but as a permanence gathered from moments of participation capable of being lived and lived again and then passed on to be taken up yet again by generations yet to come, with our own additions and our own achievements of greatness.

Republished with gracious permission from Wyoming Catholic College‘s weekly newsletter.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

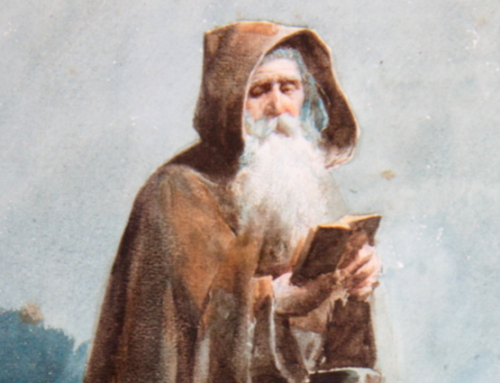

The featured image is “Tradition” (1917) by Kenyon Cox, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Tradition is a reliving of perennial truths by renewing them in contemporary idiom. But renewal does not and must not mean New Beginning. Many modern thinkers have been a victim of this heterodoxy. They have destroyed tradition in the name of renewing it. We in India are witnessing this phenomenon in the rise of neo-Hinduism.