The kinship between the Nashville Agrarians and Whittaker Chambers is seen in three main ways: the farming life itself, the concept of private property, and the religious dimension of human existence. Chambers emerges as a singular figure who, more so than the Nashville group, provides a model for those who are called to live a life of sacrifice, be witness to truth, and be devoted to the permanent values of the human spirit.

During the time that the Nashville Agrarians were putting together their first manifesto, I’ll Take My Stand (1930), Whittaker Chambers had been in the Communist Party for about five years. No known documentary evidence indicates that he was aware of their existence or—at that time—they of his. Yet in fact there was an affinity between them that, while lacking a personal connection, would manifest an underlying affiliation of mind and spirit. The Nashville Agrarians, a band of brothers dedicated to a common cultural, philosophical cause, and Whittaker Chambers—who sought a brotherhood in a malignant organization which made a mockery of true brotherhood in pursuit of its cause—had more in common than either fully realized. There were at the same time pointed differences of both style and substance.

Both in their own ways held up as a model, first of all, the agrarian mode of life, along with ownership of land, as an antidote to the twin tyrannies of rampant industrialism and the ever-growing Leviathan State. Such a state was seen as a persistent threat to personal freedom, whether in its liberal, socialist, or communist form. Part and parcel with that advocacy, especially in the case of Chambers, the ground beneath his feet became both fact and symbol for a measure of freedom from that tyranny.[1] For it is in the ownership of private property—what we casually call real estate—that one can most concretely and surely take his stand for freedom against encroachments that seek to turn the individual person into mass man. As will become clear as we go, an adherence to the land and to one’s property is also a profoundly religious commitment. As such it stands unalterably opposed to Communism, which in virtually every manifestation it has put forth is atheistic, that is, in its ideological formulations, in its adherents, and in the form of society it seeks to create.

Chambers’ story, told in Witness, in letters to friends, and in the collection Cold Friday—those fragments he shored lately against his ruin—is not simply a bit of history from the Cold War period. In fact, the significance of Chambers’ life far exceeds his anti-communist activities during that time. What becomes apparent is that Chambers’ late election of the farming life serves as a model, which, if few can follow literally, many can admire as a source of inspiration as we all make our way through parlous times and places. But even if very few can—or would want to—take such a path, many more can with sacrifice assume the role of property owners with all that it entails of rights and responsibilities and freedom. In both respects, Whittaker Chambers and the Agrarians are preaching gospel from the same text. Moreover, such commitments bespeak as well an even deeper commitment to the ground of all Being, however we may name it, that Presence in which we live and move and have our being whether we recognize it or not.

As a prologue to looking at Chambers’ involvement with farming, a brief background sketch of the Nashville Agrarians and their best-known book, I’ll Take My Stand, may prove useful. In addition to that symposium, several of the contributors also participated in a later collection, Who Owns America?, edited by Allen Tate and Herbert Agar in 1936, a source upon which I also draw for illustration.

Agrarianism in general may be defined in shorthand fashion as a way of life rooted economically and spiritually in the cultivation of the soil and the raising of livestock. Beyond that spare summation, though, the Agrarians in I’ll Take My Stand articulated a multi-faceted view of farming life that is philosophical and religious in orientation more so than it is economic. Allen Tate, a leader of the group, positioned the Southern symposium as a defense of religious humanism, an interpretation to which we will return in the third section of this essay.[2] As one of the leading interpreters of Southern literature has put it, the book holds up a “vision of a more harmonious, aesthetically and spiritually rewarding kind of human existence.”[3] The fact that many of the contributors were academics and writers and not active farmers themselves left them open to attack from some quarters. That charge is, however, essentially irrelevant to the validity of a principled defense of the agrarianism as a way of life. Dr. Johnson put the underlying principle to Bosworth in the form of a negative illustration: “You may scold a carpenter who has made you a bad table, though you cannot make a table.” Besides, the charge is not entirely true.[4]

It also probably didn’t help that their position was identified to a considerable extent with the Old South.[5] However, the book did not seek to defend the peculiar institution extant both in and outside the American South in the 18th century and even into the 19th. The symposium was neither an economic treatise, nor a political action plan, nor a sociological treatise. Moreover, it was not an attack on industrialism per se; nor did it assume that everyone in the country, let alone the South, would want, or be able, to make a living on a farm. Rather, it sought to present an image, a vision, of what the good life in that form can be. (That aside, agriculture is, to state the obvious, indispensable in one form or another.) The substantiation of that vision is amply illustrated in essay after essay, on such subjects as art, education, religion, literature, manners, and cuisine. One of the most winning illustrations of the good life may be found in the contribution by John Donald Wade, “The Life and Death of Cousin Lucius,” the concrete embodiment of a life well lived.[6]

As for the kinship between the Nashville Agrarians and Chambers, it may most readily be seen in at least three main ways, noted above: the farming life itself, the concept of private property, and the religious dimension of human existence. My main argument here is that, beyond the similarities and differences between them, Chambers emerges as a singular figure who, more so than the Nashville group, provides a model for those who are called to live a life of sacrifice, witness to truth, and devotion to the permanent values of the human spirit. This is true whether one ever follows a mule down a furrow, owns an acre or two of land, or, God forfend, testifies in a treason trial.

On the issue of farming and the life it embraces, a few observations by Andrew Lytle from both I’ll Take My Stand and Who Owns America? will serve as a preface to Chambers’ views on the same subject. Lytle had run his family’s farm as a young man and accordingly had a first-hand knowledge of agriculture as well as a cherished mode of life and the ethos associated with it. The progressive view of farming developing during this period encouraged the adoption of scientific methods as the road to riches. As Lytle quips, however, “A farm is not a place to grow wealthy; it is a place to grow corn.”[7] (It was an aim that did not, to be sure, exclude making a decent living.)

More importantly, the small farm, he argues, is a model not only for a beneficial and sustainable life but is also the foundation for freedom and independence. The farmer’s home and his means of living are combined. The commitment and the labor involved are indeed costly. But for those who are called, nothing can take its place.[8] That said, Lytle certainly recognizes that not everyone is suited for such a life. Some will lack a sense of responsibility, and others may require a larger, more lucrative field of endeavor.

Whittaker Chambers for his part would recognize in the essays by Lytle and others in both agrarian collections (1930 and 1936) what is at stake in the family-run, livelihood farm. Beginning in Witness and continuing in essays and letters, he provides an eloquent testimony to what the agrarian life offers to those able to commit themselves to it. This testimony, like all testimony based on both personal adherence to spiritual values and an engagement with the real world, illustrates what it means to live in the metaxy, the in-between that is the human lot. In other words, the vision meets the real.[9]

Here is Chambers, first of all, on the metaphysical meaning of the family farm:

Our farm is our home. It is our altar. To it each day we bring our faith, our love for one another as a family, our working hands, our prayers. In its soil and the care for its creatures, we bury each day a part of our lives in the form of labor. The yield of our daily dying, from which each night in part restores us, springs around us in the seasons of harvest, in the produce of animals, in incalculable content.

A farmer is not everyone who farms. A farmer is the man who, in a ploughed field, stoops without thinking to let its soil run through his fingers, to try its tilth. A farmer is always half buried in his soil. The farmer who is not is not a farmer, he is a businessman who farms. But the farmer who is completes the arc between the soil and God and joins their mighty impulses. We believe that laborare est orare—to labor is to pray.[10]

What one notices in this passage at first blush is that there is no straining to make a polemical point, which does tend to be the case with the Nashville Agrarians naturally enough. This is the prose, reaching toward poetry, of a man who has had the experience and carried the knowledge of it to his heart, to paraphrase a line from Tate. Here Chambers gives witness to what the family’s chosen life means to them on a daily, ongoing basis. It is a way of life, spiritually grounded, that demands hard work, but the fruit of that work is not only the produce resulting from it but the benison of a way of life not available in other modes of living. The Latin motto from the Benedictine tradition sums up the case: this way of life, with work at its heart, is itself a way of prayer. It is a way that runs counter, he goes on to say, to what the modern world is able to offer: empty comforts and pleasures without cost, the banning of mystery, and the welcoming of standardization and regimentation. It occurs to me, however, that there are those for whom such a passage is either a blank wall or romantic obscurantism, deracinated people so far gone into modernity that they can scarcely fathom what he is saying at all. It is the same mentality that saw in the Nashville Agrarians merely a romantic, sentimental hearkening back to Old Times on the Old Plantation—a perception easily triggered in those who never actually read the book cover to cover.

In similar passages in Witness and in Cold Friday, he expresses the hope that his children—a son and a daughter—would be able to continue the way of life that both he and his wife sought to provide them:

Here I determined to root the lives of my children—to live here in this particular earth—which was for them, in the routine language of deeds, ‘and their heirs and assigns, to have and to hold in fee simple forever.’ I meant to root them in this way in their nation. For I hold that a nation is first of all the soil on which it lives, for which it is willing to die—a soil bonded to those who live on it by that blood of which a man usually loses a few drops in working any field like Cold Friday… I meant to found a line rooted in a particular spot of the earth which they would make their own by that effort of their lives they put into it by working it… This was all there was to give—the ground beneath their feet. I meant to give it to them not only against the forces of open revolution but also against that suffocating materialism, which more than want or hunger, recruits the forces of the revolution in the West [emphases added].[11]

John Crowe Ransom, in his contribution to the first Agrarian symposium, had anticipated Chambers in a passage extolling the “tiller of the soil”: “He identifies himself with a spot of ground, and this ground carries a good deal of meaning; it defines itself for him as nature” [emphasis added]. Chambers in the passage just quoted, however, pointedly acknowledges that this projected way of life is not likely to be a realistic option for his children: “In the twentieth century, no purpose could have been more deliberately unrealistic. Every energy which my intelligence told me was shaping the future was against it.”[12] Chambers’ vision of a life rooted in the soil for his children was adversely conditioned by at least three factors. First of all, he himself came to farming late in life while still working at Time and was not in good health. Farming calls for at least some portion of hands-on, heavy labor, which can tax even a person in perfect health. Second, parents can influence but not choose a career for their children, and a parent’s hopes for them may be mixed. Encouraged by his father, Chambers’ son John pursued a career in journalism with the added help of Chambers’ good friend Ralph de Toledano.[13] Eventually, however, his son returned to the farm. His daughter Ellen married and moved away, while retaining ownership of a portion of the farm. Finally, the odds are set against one’s making a successful living on a farm for a variety of economic, logistical, and political reasons. Still it is a way open to the fit and the few, to paraphrase Milton. I would argue that Chambers’ vision was not quixotic so much as idealistic, one that in the case of his own family could not be perfectly realized.[14]

Yet another factor that impinged on Chambers’ view of the farming life was the insertion of the federal government into the agricultural environment. One form this took was a system of crop control in which inspectors were sent out to check a farmer’s production relative to acreage. The system also included subsidies for not exceeding a certain production level. With mixed feelings, Chambers relates that some of his farmer neighbors challenged the crop-control laws in court, but he soberly notes that if they were prepared to take the subsidies then they could not then complain about supervision. (His own solution was to abandon the growing of certain grain crops.)[15] It is clear, of course, where Chambers’ sympathies lie in the dust-up between the government and the farmer operating a family-size farm. In this he is in sync with the Nashville Agrarians. That said, one, and only one, of the many issues that lie near the conflict between the small farmer and government at all times is the moral commitment of the country to provide an abundance of food. It is crucial to the farmer that he make a living; it is also imperative that the citizens of the country don’t starve.[16]

The relation between livelihood farming and private property has already been affirmed by the testimony of both the Agrarians and Chambers. Some further development of the property issue, however, may be called for following a brief biographical-historical digression.

As noted earlier, during the time that Chambers was a Communist and the Agrarians were writing their first set of tracts, they do not, understandably, appear to have taken notice of one another. By 1952 this state of knowledge had changed on the part of at least two of the Agrarians. That year, of course, saw the publication of Witness, which produced the kind of sales the Agrarians could only hope to see and made its author something of a household name. In May of that year Donald Davidson wrote to Allen Tate partly in response to the latter’s announcement that he would soon be speaking at the Congress for Cultural Freedom meeting in Paris. Although Davidson was not familiar with this anti-communist organization, he responds with a few sharp observations on communist influences in the country. Tate’s old friend Archibald McLeish, Tate notes, was surprisingly not invited to the CCF conference. Not finding this surprising at all, Davidson asserts that McLeish was “a leader in the ‘merchants of death’” campaign against munitions makers in the mid-1930’s. The effort, directed by the Nye committee, was “communist-managed,” he adds, noting that Alger Hiss was its counsel. In the same paragraph Davidson urges Tate to “read Whittaker Chambers’ book, every bit of it, at the earliest opportunity.”[17] It is not possible from these remarks alone to discern exactly what resonated with Davidson about Chambers’ book as a whole, but my hunch is that it was far more than its anti-communist message and his testimony at the Hiss trial. If that is all he saw in it, he would, I think, have missed its most important part, as I argue here. Some six years later, Chambers makes an intriguing reference to the Agrarian culture of the American South in a letter to William F. Buckley, Jr.:

Only the American South sought to persist in the past, as an agrarian culture, resting on slaves instead of serfs. To wipe out this anachronistic stronghold, above all to break its political hold on the nation as a whole, the emergent capitalist North fought with it what amounted to a second Revolution….[18]

Is it possible to see in this passage an oblique reference to the Agrarians? Probably not. Some Southerners, Davidson included, also saw the War of 1861-1865 as a second revolution, but one in which they were attempting to return the country—or at least their part of it—to the principles of the first. My hunch is that if Chambers had had the Nashville group in mind, he would have been explicit. In any event, Chambers’ main point to Buckley is that the north prevailed largely through its industrial might, and that factor subsequently changed the economic-political course of the country in an unparalleled, anti-conservative fashion. (The cataclysmic effect of Yankee industrial power in that War was not lost, of course, on Davidson and others.) Whether he ever took notice of them, it is clear that Chambers’ viewpoint in this instance puts him at odds with that of the Agrarians. Each reflects certain typical perspectives of his region.[19]

It is no secret that Communism has historically sought to annul private property as a fundamental proposition. Marx, moreover, demanded recognition of the state of affairs in which a majority of people own none, apparently as a pre-emptive strike against a self-interested defense by those who own some.[20] What Marx seems to assume of course is that this majority is capable of owning and being a steward of property. (The naiveté of such an assumption suggests that he never had hands-on experience in the real estate business.) We have also seen the commentary by Mr. Lytle suggesting that many are just not up for it. It is not necessary or fruitful to rehearse in detail the arguments in favor of the annulment of property; they are already well known to those familiar with Marxist ideology.

A more fruitful exercise is to examine an apologia for private property from a philosophical perspective. A compelling one happens to exist fortuitously enough in a book by a serious student of the Agrarians, one who in fact studied under them at both Vanderbilt and LSU and who, partly through their influence, underwent a conversion from socialism to a traditional conservatism with a Southern orientation. I refer of course to Richard Weaver’s Ideas Have Consequences (1948) and in particular to the chapter entitled “The Last Metaphysical Right.” One of Weaver’ primary points is that the unity of owner and owned means that “something’s being private property removes it from the area of contention.”[21] The ethical answer to Marx is a fair distribution of properties, such as small farms and businesses, as well as houses occupied by the owners themselves.[22] As with farming itself, not everybody is up for property ownership in any form; and many would not want it. The thoroughgoing relativist, socialist, or Marxist cannot, of course, accept the basis of Weaver’s argument, given their derogation of the individual as such.[23]

One addition to the discussion by a leading Agrarian may suffice. Allen Tate in his Who Owns America? essay advances a defense of private property with an emphasis on individual ownership as contrasted with that exercised by a corporation. The latter is analogous to political collectivism. The only ownership that means anything for individual liberty is that controlled by the individual. It is the same argument that Weaver makes; the very concept of corporate ownership is a violation of proprietas. In fact, the behemoth corporation is “the enemy of private property in the same sense as communism is.”[24] Tate, while objecting to the final title of the first symposium, also did not care for “Tracts Against Communism” as an alternative. He believed that the arguments the group put forth were inherently and self-evidently anti-communist.[25]

Finally, Chambers himself, in a letter to his son published in Cold Friday, makes the case for private property, whether farmed or not, as a bulwark against encroachments on freedom. The concept itself is abstract, but what signifies its reality is the fence, which is practical, concrete, and symbolic all at the same time:

A fence is a definition and what it helps to define is that ownership of property which is the final guarantee of freedom. It cannot be breached without breaching freedom, and if it is ended, freedom is ended. Property is the ultimate guarantor of freedom. The benevolence of those who would deny this has nothing to do with the case.[26]

It is hard to say precisely what he has in mind with the reference to misplaced benevolence, but one recalls a well-read poem by that New England Agrarian who muses with ironic intent on the purpose and meaning of fences. Whatever interpretation one settles on regarding Frost’s text, it is the enlightened (as they see themselves) and “benevolent” ones who would on principle prefer that fences not be built in the first place. We call some of them Marxists.[27]

The connection between farming and private property is readily apparent. That these are also spiritual in nature is less so. But we recall what Chambers wrote, cited earlier: “Our farm is our home. It is our altar. To it each day we bring our faith, our love for one another as a family, our working hands, our prayers.” The land, the farm is the concretization of the love and spiritual life of the family. The three components—farming, property, the spiritual life—while not melded into one another, are nevertheless interrelated. Moreover, what becomes clear as we read Whittaker Chambers’ reflections on his religious pilgrimage is that it was not merely a movement, a conversion as an intellectual exercise. It was an experience of an existential order, and it would scarcely be an exaggeration to say it was for him a matter of life and death. To do full justice to its depth, breadth, and richness would require a much more comprehensive treatment than can be provided here. We will touch on only a few salient features. (In a searching essay on “modernism,” Marion Montgomery alludes to Chambers’ conversion as comparable to those of T.S. Eliot and Richard Weaver as “persons turning a key from within Gnosticism’s self-imprisonment.”[28])

By way of both preface and comparison-contrast, we turn first to representative comments by two Agrarians on the relationship between religion and the agrarian life. For Lytle, first of all, the connection between farming and faith is transparent and inherent in the nature of things—that is to say, in nature. The farmer, if he is clear-eyed, knows he cannot conquer nature. He recognizes that he is faced with “a mysterious and powerful presence,” over which he may exercise stewardship but which he can never subdue to his will or wish. He leaves speculations about the prospect of radical change to others.[29]

Allen Tate, in his contribution to the first symposium, takes a decidedly philosophical approach to religion, which on a practical level has oddly nothing much to do with agriculture. Moreover, far from being a personal engagement with faith, his essay seeks to differentiate the Southern mode of religion from that of other regions. First of all he calls out those theologians and Biblical scholars who since the 19th century had engaged in a type of textual analysis of Scripture that led in a straight line to a relativistic interpretation of the Bible in general and of the nature of Christ in particular. They, in short, represent the Long View, which is “the cosmopolitan destroyer of Tradition.” In short, since the Christian religion is simply a variation on innumerable vegetation myths, there is no compelling rationale for one’s electing Christ over Adonis. The Short View by contrast posits that Christ is utterly unique, and although, as C.S. Lewis might say, certain myths prepared the way for Christianity, our tradition—the Southern one in particular—enjoins us to take the whole, distinct Christ over the half-loaf offered by the relativists.[30] In other words, it is a religion to which one could adhere for the sake of living one’s life in the light and surety of accepted dogma. A traditional religion for a traditional and predominantly agricultural section. As such it was free of the intellectual debates which in the New England Puritan mind led ultimately to Unitarianism and in some cases to the abandonment of faith altogether.[31]

Whereas Tate’s address to the subject of religion here strikes one as youthful, amateur theologizing, that of Chambers, beginning with Witness, represents a reaching for a faith that he hopes will be a means of salvation. (The two approaches illustrate the difference between a passenger on an educational cruise and a man, fallen into the water, yelling for a lifesaver to be thrown to him.) The most appropriate place to begin with Chambers’ conversion and pilgrimage is with an early passage in Witness that may best be described as an epiphany. His conversion has only just started. Partly because of the Russian purges (disclosed in 1937), he has begun to question the nature of Communism and his allegiance to it. Before the epiphany occurs, however, and as he seeks to extricate himself from the intricate web of Communism, Chambers begins to pray. This gesture at first was rough and ragged, but it was a beginning. In time a transformation began taking place in which he was able to see that the real change that must take place in him was not just a matter of affiliations—from Communism to Christianity. He had first to reject the mentality that “denies… the soul’s salvation in suffering in the name of man’s salvation here and now.”[32] The organization of the world by man alone, without reference to God, will end up by working against man in a most lethal manner.[33] His account of this early phase of his conversion experience should be read in its entirety, but I shall cite only enough of it to capture its flavor:

Then there came a moment so personal, so singular and final, that I have attempted to relate it to only one other human being, a priest, and had thought to reveal it to my children only at the end of my life… One day as I came down the stairs in the Mount Royal Terrace house, the question of the impossible return [to life without Communism] struck me with sudden sharpness… As I stepped down into the dark hall, I found myself stopped… by a hush of my whole being. In this organic hush, a voice said with perfect distinctness: “If you will fight for freedom, all will be well with you”… What was there was… an awareness of God as an envelopment, holding me in silent assurance and untroubled peace.”[34]

A number of things are noteworthy here. Like many a religious experience before this one, it is intensely personal, intuitive, emotional. Reason is not abandoned; it just has no place in this moment. He goes on to say that during—or from—this time he gained a peace and strength that stayed with him even through the Hiss trial and beyond. Strangely perhaps, however, he did not seek fully to know God’s will. With Kierkegaard, he felt that such knowledge is beyond man’s ken. It was enough that he was enabled to walk “into life as if for the first time” and to offer that life up as he was able.[35]

The passage cited here, reflecting on the early phase of his conversion, is at the heart of both the book and Chambers’ life itself. That is to say, his “witness” is not simply the testimony he went on to give in the Hiss trial, as crucial as that is to his story. That part pertains mostly to politics. Being a witness in the fullest sense entails the willingness to sacrifice oneself for the sake of truth, often the truth of faith. Those familiar with the term “martyr” will recall that the literal meaning of that Greek-derived word is “witness.” Alluding to that origin in a 1954 letter to Buckley, Chambers makes the larger point that many had missed about his book. It was not that if you defeat Communism you can go back to your life as if nothing had happened. No. Rather, you must be willing to struggle and even to die so “that your faith may live” and you can recover your greatness as spiritual beings. (It must be stressed that he does not mean merely himself here.) He had said the same thing even more forcefully in Witness, adding for emphasis there that a man must be prepared to destroy himself.[36] As Chambers acknowledges, for those who operate from the far reaches of rationality and intellect, such talk is nonsensical and even patently morbid. And from that perspective, of course it is. (One might say that for the Communist the only permissible “martyrdom” is someone else’s; from the Christian point of view the only permissible martyrdom is one’s own.) On the other hand, if one’s faith is not worth dying for, then the question remains open as to whether it is worth living for. On that question indeed hinges how one interprets Witness and Chambers’ life in general. Moreover, not everyone is called to be a martyr in the ultimate sense, but if no believers are ready to risk themselves for a given cause, then their faith—secular or religious—is not going to be very engaging to very many people. More to the point, it may have no real substance.

This is the very issue Chambers fastens on in his reading of Henri de Lubac’s The Drama of Atheist Humanism, a book he refers to as “indispensable.” In a letter to Buckley, he singles out a striking passage from it in which Lubac notes that while the “best” may be drawn to the Church, in which they sense the answer to the deep questions of our destiny, some of them stop on the threshold. Why? They look at who we are, the Christians of today, and simply “cannot take us seriously.”[37] It’s not that they condemn such Christians; rather, they see them as lukewarm and hence not very impressive.

What is impressive is man’s capacity for enduring suffering for the sake of his faith. (It is in fact a form of martyrdom short of death.) Partly as a result of his own experience of suffering resulting from his testimony in the Hiss trial, Chambers elevates that experience as the key criterion for measuring religious commitment: “Suffering is at the heart of every living faith. That is why man can scarcely call himself a Christian for whom the Crucifixion is not a daily suffering.” The willingness to endure trial for one’s faith is a testimony to “the greatness [that] inheres in every man in the nature of his immortal soul, though not every man is called upon to demonstrate it.” What is typical of the current age is an obsession with avoiding suffering, which is a retreat into infantilism where growth is impossible. Elsewhere in Cold Friday, Chambers notes that in time he came to see that “charity without the Crucifixion is liberalism.” Flannery O’Connor couldn’t have said it better.[38]

As the reference to Fr. Lubac’s text and Chambers’ emphasis on the centrality of suffering might suggest, Chambers saw in the Catholic Church a witness in itself, a bulwark in a chaotic world. He writes to Buckley in October of 1956:

There is only one fully conservative position in the West—that of the Catholic Church… Moreover, the Church is the only true counterrevolutionary force, not because it is against the political revolution in this world, but because it contains the revolution wherever the revolution manifests that wound.[39]

Allen Tate, alone amongst the Agrarians, had also come to see the Catholic tradition in much the same light as Chambers: it was “the vital force in Western history, the only coherent system of thought which could save the culture from fragmentation.”[40] As a sign that this view was more than cultural, he entered the Church in December of 1950, following his first wife. Unlike Tate, however, Chambers could not see his way into the Church, and that for various reasons. Tate’s own voyage in the bark of Peter was not, as it turned out, a case of smooth sailing through the time’s troubled waters. His late conversion (though it had begun in the late twenties), along with a marital career bearing some burden of irregularity, did not smooth his integration into the fold.[41] Among the obstacles for Chambers was the perception he shared with Ralph de Toledano that the Church existed “in the City of man, not the City of God.” Another issue which Toledano also touches on is the Third Rome myth with which Chambers was intrigued.[42] The subject of Chambers, the Catholic Church, the Third Rome concept, and indeed his entire religious pilgrimage, calls for a fuller treatment on another occasion.[43]

For now suffice it to say that the example Whittaker Chambers, along with that of Nashville Agrarians, is of value to us today beyond his and their respective roles during the Depression period, World War II, and the Cold War era. To see Chambers in particular only as a key figure in the Hiss trial and its aftermath is to miss or to misconstrue his import. His witness, again, was not simply against treason or Communism itself. It was against an ideology, a species of Gnosticism, that seeks to achieve its ends—forms of man-made utopia—at the price of the destruction of the human spirit.[44]

Ralph de Toledano in an annotation to one of Chambers’ letters to him recalls a remark by Sidney Hook, the Jewish agnostic philosopher, who had written a balanced review of Witness two years earlier. Hook admonished Toledano for his allusion to the sense of mystery (in a religious sense) in Chambers’ writing. He says, “But why, Ralph, does he have to bring God into it [?]”[45] Indeed, why? One need not travel to the ends of the earth for an answer. Chambers provides it: “The crux of this matter [the struggle against Communism] is the question whether God exists. If God exists, a man cannot be a Communist, which begins with the rejection of God. But if God does not exist, it follows that Communism, or some suitable variant of it is right.”[46] Indeed, the “crux” of the matter lies in how one answers the God question; it lies for Whittaker Chambers in the Cross for it is paradoxically in that sign that the futility and emptiness of man-made attempts at secular salvation become transparent and the scales fall away. It is the Cross and its salvific meaning, pointing to our supra-temporal destiny—the life beyond life—that is the ultimate “ground beneath our feet.” The rest is shifting sand. “The cross stands while the world turns,” as the Carthusians have it.

Chambers knew as well as anyone the cost of engagement in the politics of his time. That story, too, is of course told in Witness. Chambers would surely have appreciated the more recent testimony of another Christian pilgrim, forcibly exiled from the Russian matrix of the Marxist dream, which he delivered to the graduating class of Harvard University in 1978:

On the way from the Renaissance to our days we have enriched our experience, but we have lost the concept of a Supreme Complete Entity which used to restrain our passions and our irresponsibility. We have placed too much hope in politics and social reforms, only to find out that we have been deprived of our most precious possession: our spiritual life.[47]

Chambers would have understood these words better than anyone in that audience that day. Solzhenitsyn’s speech as a whole was at best awkward for the inviters, who, unlike their guest, might have no quarrel with “an autonomous, irreligious humanistic consciousness”—against which the speaker had set his face like flint.[48] They were not likely to make the same mistake again, “Veritas” or no “Veritas.” A Fugitive-Agrarian late of north Georgia, Marion Montgomery, saw in Solzhenitsyn a “Southern” cousin and likens his From Under the Rubble to I’ll Take My Stand in which later book the Russian distinguishes between “men of the soil,” whom he honors, and the “people of the air,” a sobriquet suggesting a certain rootlessness.[49] They are still with us today. But the good news is that, apart from Solzhenitsyn, there are other witnesses influenced by the Agrarians—among them Flannery O’Connor, Walker Percy, and Montgomery himself. These and others have also in various ways challenged such rootlessness and its cousin, “the tyranny of relativism” (in Pope Benedict’s apt naming).

Whittaker Chambers’ life, works, and witness should alert us that in the face of existential threats from Marxism, the radical left, anarchists, assorted Gnostics, et al., there must be some on the right who are willing to step into the breach and risk their peace, their reputations, their livelihoods, and more for the good of the community as a whole. Some may do this in the political arena, the classroom, or the ordained ministry; some may do it primarily within the family; others may take a stand on the issue of private property and others for the sake of the innocent unborn. Still others may in the present age have to risk all for the sake of the freedom of thought and speech, so sorely threatened of late (2021) by the demi-gods of social media, along with their allies in the mainstream media and government. (A rare few may even elect to commit themselves to the agrarian life in one way or another.) There are surely other forms of witness unnamed here. But whatever form that witness takes, those who know who Whittaker Chambers was will also know that they are not alone. The road has been taken before and is well travelled.

Chambers was no saint. He is, like the rest of us, fallen and fallible, but he was gifted with a brilliant, subtle mind who over his too-short life gained and shared knowledge, insight, humility, and above all wisdom and courage. These are qualities that will stand us all in good stead, and we will find them modeled in him if we take the trouble to make his acquaintance. We can know him insofar as we can know anyone who has departed this vale of soul-making in his books, his letters, his essays, and in the works of those who have written fairly about him. I close with a simple injunction: Read him.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Notes:

[1] A variant of the phrase, “the ground beneath their feet,” is found in a collection of Chambers’ writings, Cold Friday, ed. Duncan Norton-Taylor (New York: Random House, 1964), 44, where he provides eloquent testimony to the meaning and purpose of land, especially land devoted to agriculture. As will become clear, in light of Chambers’ own reflections, I use the term more expansively to refer ultimately to the ground of being, that is to say, the supernatural reality undergirding the known, sensible world. Granted such a designation is a stretch but one justified by Chambers’ own thought, which I follow, and of course that of Tillich who popularized the concept. For Tillich, it is a figure; for Chambers, a symbol.

[2] Louis Rubin, Introduction, Twelve Southerners, I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1977), xxxiv. Robert Penn Warren had proposed “Tracts Against Communism” as an alternative title.

[3] Ibid., xxxii.

[4] See James Boswell, Life of Samuel Johnson (New York: Alfred A. Knopf/Everyman, 1992), 257. Andrew Lytle for one had run the family farm as a young man but at a certain point had to choose between farming and writing fiction. Both required similar “creative energies.” He chose the latter. See Tom Landess, “The Fugitive-Agrarians: Personal Recollections,” in Life, Literature, and Lincoln: A Tom Landess Reader (Rockford, IL: Chronicles Press, 2015), 64. Other Agrarian members, having grown up in a predominantly rural section, had at least some close-hand knowledge of farming life. Some folks clearly have much less, however. I recall a remark by a 2020 presidential candidate on the nature of farming: “I could teach anybody… to be a farmer… It’s a process. You dig a hole, you put a seed in, and you put dirt on top, add water, up comes the corn.” One would have to search far and wide, high and low, for language sufficient to describe the vacuous intellectual state such a locution represents.

[5] Stark Young, in his offering in the first symposium, writes that “we defend certain qualities not because they belong to the South, but because the South belongs to them” (335-336), a distinction totally lost on those who have predetermined that no good can come out of the land below the old surveyor’s line.

[6] On the purpose of the book as a whole, Richard Weaver, in “Agrarianism in Exile,” Southern Essays of Richard M. Weaver, ed. George M. Curtis, III and James J. Thompson, Jr. (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1987), notes: “The principal target of its attack was the theory of progress, and the embodiment of that theory was the North, victorious in war and victorious in trade…” ( 37). We will encounter Weaver again in the section on property.

[7] Andrew Lytle, “The Hind Tit,” I’ll Take My Stand, 205. Lytle’s graphic title employs a metaphor for what could happen to a farmer faced off against both the industrialist and a large farm operation using “scientific” methods. He will be like the “runt pig in the sow’s litter” getting at best the small hind tit (245).

[8] Andrew Lytle, “A Small Farm Secures the State,” Herbert Agar and Allen Tate, eds., Who Owns America?:A New Declaration of Independence (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 1999), 310-311.

[9] The term metaxy as I use it here refers simply to the challenge facing a person with values and ideals of reconciling those with life in the so-called “real world.” The term is borrowed from Eric Voegelin, in whose writings, and in commentaries on his writings, the term is rather more complex and freighted. See here.

[10] Whittaker Chambers, Witness (New York: Random House, 1952), 517. In the same year that Witness was published, Chambers had written an essay for Commonweal entitled “The Sanity of St. Benedict.” While some may choose to see that essay as an expression of nostalgia, for others it is a statement of how to conduct oneself between the extremes of capitulation to corruption, on the one hand, and asceticism and denial, on the other. See Ghosts on the Roof: Selected Journalism of Whittaker Chambers, 1931-1959, ed. Terry Teachout, 257-264 (Washington, D.C.: Regnery Gateway, 1989.

[11] Cold Friday, 40, 43-44.

[12] John Crowe Ransom, “Reconstructed but Unregenerate,” I’ll Take My Stand, 19. Cold Friday, 43-44.

[13] Ralph de Toledano, Notes from the Underground: The Whittaker Chambers-Ralph de Toledano Letters: 1949-1960 (Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing, 1997), 317.

[14] According to the USDA, the percentage of farm workers (not counting paid employees) has for several decades hovered somewhere around two percent. This is a far cry of course from those engaged in farming during the 19th century. That 2% does not, however, take into account hired farm workers or those employed in one way or another in agricultural-related enterprises of various types. See here.

[15] Whittaker Chambers, Odyssey of a Friend: Whittaker Chambers’ Letters to William F. Buckley, Jr., ed. William F. Buckley, Jr. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1969), 80.

[16] One Illinois farmer and ag industry employee with whom I have corresponded recently put it this way: “Most farmers would prefer an open market, but realize that cheap food and energy are [morally] fundamental to the US.” It is yet another case where a certain philosophical view conflicts with the ethical obligation to provide one of the essentials of life.

[17] Donald Davidson to Allen Tate, Literary Correspondence of Donald Davidson and Allen Tate, ed. John Tyree Fain and Thomas Daniel Young (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1974), 365. To date I have found no evidence that Tate in fact read or subsequently remarked on Witness; nor did Davidson write further about the book as far as I can tell. He had edited a book review page for the Nashville Tennessean from 1924 until 1930, but it was cancelled as the Depression was getting underway. See John Tyree Fain, Introduction, The Spyglass: Views and Reviews, 1924-1930 (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1963), xiv. A review of Witness was, however, published in the paper on May 25, 1952 by Aubrey C. Lang. See here.

[18] Whittaker Chambers, Letter to Buckley, Christmas Eve, 1958, Odyssey, 228. One cannot help noticing Chambers’ use of “serf” with its association with Russia.

[19] Whether Chambers took formal notice of the Nashville group, his friend and fellow Time writer, James Agee (a Tennessean by birth), did so in a short series of satirical poems written in the 1930’s. The second of these, entitled “Agrarian,” opens thus: “In the region of the T V A / Of the cedars and the sick red clay / We’ve discovered a solution / Neither Hearstian nor Roosian / In the embers of a burnt out day,” Collected Poems of James Agee, ed. Robert Fitzgerald (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1968), 146. Editor Fitzgerald was yet another Time veteran and is mentioned in Witness (478). The Agrarian “solution” that Agee’s speaker offers here lies between the leftist New Deal—both Rooseveltian and Russian—and that of William Randolph Hearst, turned enemy to the President. Agee, like Chambers, had an extended revolutionary (i.e., Communist) phase. I owe the parsing of Agee’s pun, along with other key insights to, Hugh Rollin Davis, “The Making of James Agee.” PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2005. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/4310, 72-77.

[20] See Karl Marx, “Manifesto of the Communist Party,” Marx-Engels Reader, ed. Robert C. Tucker (New York: W.W. Norton, 1978), 486. For additional references to the annihilation of private property see also the following pages: 82, 120, 484, 487, 505. Eric Voegelin, a German philosopher of a later generation, one compelled to flee the Nazis at the outset of WWII, critiques certain fallacies—or, more exactly, willful distortions—in Marx’s thought in Science, Politics, and Gnosticism: Two Essays (South Bend, IN: Gateway Editions, 1968), 35-36.

[21] Richard M. Weaver, Ideas Have Consequences, Expanded Edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1948, 2013), 120.

[22] Ibid., 121.

[23] As Chambers writes, “In Communism the individual is nothing,” Witness, 720. In Christianity, we might add, the individual, while not “everything,” is certainly a sine qua non.

[24] Ibid., 120. Allen Tate, “Notes on Liberty and Property,” Who Owns America?, 113.

[25] Allen Tate, Literary Correspondence, 41.

[26] Cold Friday, 60.

[27] Robert Frost, “Mending Wall,” Collected Poems, Prose, and Plays (New York: Literary Classics of the United States, 1995), 39-40. The enlightened ones, referred to in my text, do in fact build fences for themselves. It is sometimes the case, however, that they object to other peoples’ doing so whether on private property or on the borders of sovereign territory.

[28] Marion Montgomery, “Modern, Modernism, and Modernists,” The Truth of Things: Liberal Arts and the Recovery of Reality (Dallas: Spence Publishing, 1999), 275.

[29] Lytle, “The Small Farm Secures the State,” Who Owns America?, 322-323.

[30] Allen Tate, “Remarks on the Southern Religion,” Essays of Four Decades (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 1999), 162-163. For more on Tate’s own spiritual journey as Catholic, beyond what little is provided here, see Peter Huff, “Allen Tate and the Catholic Revival,” Humanitas, 8, no. 1 (1995): 26-42. The distinction Tate is making here is similar to that between Eucharistic bread seen as mere symbol and as real presence.

[31] Richard Weaver in “The Older Religiousness of the South,” Southern Essays, 134-146, picks up where Tate left off on the distinctiveness of the region’s Christianity. He writes, for instance, “The religious Solid South expressed itself in a determination to preserve for religion the character of divine revelation” (136). The recourse to reason as an absolute would lead inevitably to dissension and conflict.

[32] Witness, 83.

[33] Chambers goes on to say in this passage that “The gas ovens of Buchenwald and the Communist execution cellars exist first within our minds,” minds, that is, which arrogate to themselves man’s salvation in this world alone by man himself. One is reminded of Flannery O’Connor’s similar reference in her “A Memoir of Mary Ann” in which she alludes to what happens when the “tenderness” with which some would govern is cut off from Christ: “It ends in forced labor camps and in the fumes of the gas chamber,” Collected Works (New York: Literary Classics of the United States, 1988), 830-831. See also Walker Percy’s Thanatos Syndrome, (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1987), in which Fr. Smith asks his listeners: “Don’t you know where tenderness leads?… To the gas chambers” (361). Apparently Percy unconsciously borrowed the line from O’Connor as he acknowledged in a late interview.

[34] Witness, 82-84. This sense of mystery, “the tremendum,” is referenced again in a letter from Chambers to Ralph de Toledano of 1954, Notes From the Underground, 178-179.

[35] Witness, 85. Chambers references the Danish philosopher several times in Witness and in the essays collected in Ghosts on the Roof.

[36] Odyssey, 62; Witness, 700, 762-763.

[37] Chambers, Odyssey, 264-265. See also Henri de Lubac, The Drama of Atheist Humanism (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1949, 1983), 123-124.

[38] Cold Friday, 86-87, 95. Richard M. Reinsch, II has an incisive commentary on Chambers’ understanding of suffering in relation to man’s service to liberty and truth in Whittaker Chambers: The Spirit of a Counterrevolutionary (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2010), 47-48.

[39] Odyssey, 137-138. See also a similar remark about the Church in a letter to Buckley of July, 1957: “Only the Catholic Church has dared to look steadfastly at that torrent, and measure what it costs a man’s soul to make its passage, not in terms of deflecting hope, but in terms of what cruelly is” (Odyssey, 191). The “torrent” I take in this context to refer to various “isms,” among them terrorism, nihilism, communism.

[40] Huff, 32. An associate of mine and a student of Donald Davidson suggested that Davidson had been drawn to the Church but did not finally cross the Tiber.

[41] For Tate’s early movement toward the Church, see Literary Correspondence, 223: “I am more and more heading towards Catholicism,” he writes Davidson in 1929. For his checkered marital status, see Huff, 39-40. Another point of difference between Tate and Chambers was that the former, after the 1930’s, continued to promote various “back to the land” initiatives associated with the American Catholic Revival movement (Huff, 38-40). Chambers, on the other hand, sought no agrarian associations beyond the informal ones with his farmer neighbors.

[42] Toledano, Notes from the Underground, 314. The Third Rome myth in brief holds that Moscow is both the political and spiritual center of the world, replacing both Rome and Constantinople. See Chambers to Toledano, July 3, 1957, Notes, 301. Eric Voegelin in the New Science of Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1952), 113-115, sees the concept as a species of Gnosticism embodying the misguided attempt to merge secular and spiritual powers. For him, the church is the appropriate domain of spiritual power.

[43] With regard to Chambers’ church affiliations, he had as a youth attended Episcopal Sunday School (Witness, 115); he was baptized at the Episcopal Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City in September of 1940 (Sam Tanenhaus, Whittaker Chambers: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1997), 165, 558); and for much of his life he identified as a Quaker. However, toward the end he had soured on the Society of Friends. During the Hiss trial, they had been decidedly more friendly to Hiss and company, and in 1951 his daughter’s application to a certain prestigious Quaker college was apparently blackballed because of the administration’s alignment with Hiss (Tanenhaus, 474). Intriguingly, Chambers was acquainted with a sizeable number of Catholic priests to whom he refers in letters and other writings.

[44] This ideology operates directly and indirectly. It works both through terror and violence and through the slow attrition of Cultural Marxism that aims to destroy a people’s confidence in its traditions and culture as a whole, bit by bit. This handmaid of Communism seeks to destroy the past that it finds offensive and means to make it a cultural—and eventually legal—crime to see any redeeming value in those persons who have, by the ideological arbiters, been condemned. If one has been accused of racism or some form of sexism, he or she is totally evil and must be utterly destroyed and erased. And if one has worked for a recent President during his one and only term, he or she must be blacklisted in a manner that was condemned when it was practiced by Sen. McCarthy in the 1950’s. It is the madness of 1984 all over again, revived and updated for 2021, and writ large.

[45] Notes from Underground, 180.

[46] Cold Friday, 68-69. Flannery O’Connor in a letter to a friend makes a cryptic comment: “The Communist world sprouts from our sins of omission,” The Habit of Being, ed. Sally Fitzgerald (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1979), 450. In other words, if Christians responded to the needs of others in the community with charity—real, costly charity—there would be no need for the response of an ideology which aims to effect a secular utopia and ends up establishing hell on earth.

[47] Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, “Harvard Address,” The Solzhenitsyn Reader: New and Essential Writings, 1947-2005, ed. Edward R. Ericson and Daniel J. Mahoney (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2005), 574.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Marion Montgomery, “Solzhenitsyn as Southerner,” Men I Have Chosen as Fathers: Literary and Philosophical Passages (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1990), 148, 153. See also his “The Agrarians Here and Now,” in On Matters Southern: Essays About Literature and Culture, 1964-2000, ed. Michael M. Jordan, 114-119 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2005).

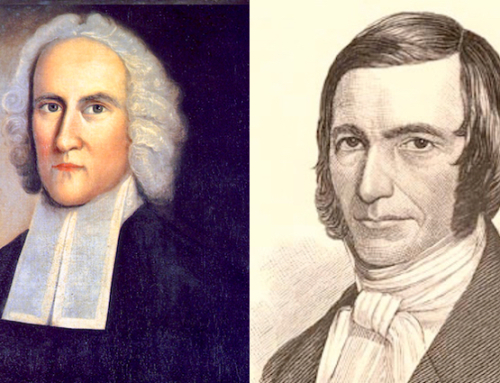

The featured image is “Potato Planters” (c. 1861) by Jean-François Millet (1814–1875) and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The in-text image is a photograph of Whittaker Chambers (1948) and is also in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

What an impressive article, Dr. Hubert!

This is a most thoughtful, well-considered essay, with much to ponder and take to heart. Thank you, Thomas Hubert; and thank you, The Imaginative Conservative.

49 Footnotes. This is a book-kength manuscript. I would like to see the more succinct summary so that it could more easily be shared and used to persuade others. But for post-election 2021, this is a sobering and helpful read. Having once lived on a mere five acres in Oregon, my husband and I both realized our complete inadequacy as tillers of land. At least we got some nice sheep wool out of it, to remind of our time in the sun and of the beauty of those animals.

You are right, of course. It is too far on the long side for most folks.

Your experience on a farm and reference to sheep reminds me of a story told at a retreat by a married couple who raised sheep for a living, among other farming activities. The sheep were kept initially a mile or so from where they lived. One night, wolves attacked and did predictable damage. They then decided that they would have to live with the sheep close by if they were going to be true shepherds. It’s not a life for everyone, to be sure, but they knew it was the life for them.

Super thoughtful essay, Sir. Thank you.